The film crew of Rooted in the Soil are videoing a panoramic view of the Nu River from the top of a high mountain.

IN December 2020, the documentary film Rooted in the Soil directed by Chai Hongfang for the CCTV news channel premiered nationwide. Based on China’s poverty alleviation endeavor, it took nearly four years to produce and can be considered a distilled version of the journey and eventual culmination of that goal.

“Rooted in the Soil tells the story of changing fate of a remote and poverty-stricken mountain village in Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture, Yunnan Province. The film focuses on the poor people and shows how the local government and locals have bravely faced and overcome poverty in the context of China’s war against poverty,” said Chai. She delved into the story of the film and the story behind the film.

Farmers of Shawa Village working in their rice paddies.

A Chronicle Spanning Four Years

On May 17, 2017, Chai assembled a nine-person filming production team from Beijing and Yunnan to settle in Shawa Village, Pihe Township in Fugong County of Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture. They planned to stay in this remote mountain village in southwest China for a long time to shoot a documentary film that documented the changes that occurred during China’s poverty alleviation drive. “There was no script for the documentary. To carefully record the whole process of poverty alleviation in this mountain village, I spent much time and energy in planning how to shoot the film,” Chai said. Before entering the village, she had made preparations for a long-term stay. In her mind, shooting the process of poverty alleviation was as hard as the local poverty alleviation campaign itself.

Before she entered the shooting location in May 2017, Chai Hongfang and the planning team explored the whole prefecture of Nujiang. Finally, they chose Shawa Village of Pihe Township in Fugong County. After she spent six hours climbing up the mountain to Shawa, the scene that unfolded in front of her mesmerized her. “The distant mountain was surrounded by fog and mist, the paddy fields were glittering gold under the sun, the children had the run of the entire village, and the working villagers wiped the sweat from their foreheads with their sleeves from time to time,” recalled Chai. The isolated, beautiful, and simple village in front of her eyes was the ideal location for filming. “Although poor, the small village had access to water and irrigable land to be self-sufficient. The root of poverty lay in the fact that there was no easy way into or out of the mountain here,” she said.

Villagers harvesting rice.

Shawa Village is very beautiful, but the living conditions turned out to be extremely difficult. On their first night in the village, Chai made it clear to her team, “If anyone of us wishes to quit, it would be best to leave tonight. Otherwise we have to stay here until the end.” Chai spoke this way and did things in a clear, direct manner, issuing the simple ultimatum to each team member. “Because the conditions in Shawa Village were so difficult, we would not be able to shoot here for a month or two, maybe a year or two, or even longer. I was afraid that everyone would give up halfway through,” Chai said. She added that it was the biggest adventure of her life to take her team to the village.

“An abandoned primary school classroom, three old desks, several old benches, and several computers constituted our editing room. The dormitories of the team members were close to pig pens of the villagers. Every morning, we did not wake up to the crowing of chickens, but were often awoken by the snoring of sows and the squealing of piglets. In summer, all kinds of insects crawled on the walls and beds. In such an environment, everyone had to get over a psychological barrier,” said Chai. The first thing the team members had to do in the village was to learn how to adapt to the environment.

The harsh environment was not that terrible, the issue was that this group of “aliens” could not integrate into the villagers’ lives easily. “Because it had been in a state of isolation for a long time, few people from the outside world came to the village. The villagers were quite shy around outsiders. When the team first entered the village, the villagers would immediately hide or run away at first sight. There was little to no communication with them,” Chai recalled. Such a situation is a fatal obstacle for the production of a documentary, which would have held their follow-up work back, according to her.

The happy moments of children in Shawa Village are shown in the documentary film.

Chai quickly found a local villager who was experienced, educated, and fluent in Mandarin, Aden Yan, and explained to him the purpose of the filming team’s trip, hoping that with his help, the villagers would lower their guard and cooperate with her team.

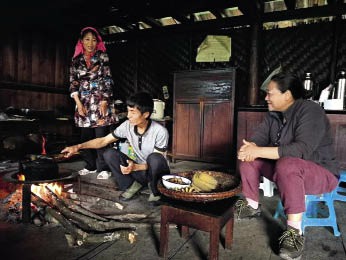

“Every day, I stood on an elevated ground in the village and greeted the villagers who went to work in fields and passed by. Initially, everyone ran away as soon as they saw me. Later, I often invited them to sit down with us. I cooked for them personally. In this way, the villagers gradually became familiar with us and did not hide from us any more. We soon learned about their respective lives. As a result, we decided on the main characters to be filmed,” said Chai. These characters include poor villagers Po Luo and Li Jianhua, poverty alleviation team member Zhu Yun, and Laba, the children’s representative. They are typical representatives of the poor people and their struggles. “The changes in the fate of these small potatoes are exactly the changes that China’s poverty alleviation has brought to 700 million farmers. Although the characters and stories are small, they represent the changes of a group and reflect the profound changes occurring in Chinese society,” Chai noted.

Living and shooting in Shawa Village for more than 1,000 days and nights, Chai and her shooting and production team overcame the physical discomfort brought by the harsh environment, and endured the loneliness and desolation from staying deep in the heart of an isolated environment for a long time. What they presented to the audience was the final product of monumental effort. “The four years we filmed in the village were the most critical period for China’s poverty alleviation. More than 50 million rural poor people across the country were lifted out of poverty. Rural poor people generally are free from worries over food and clothing and have access to compulsory education, basic medical services, and safe housing. With the help of the government, Shawa Village was lifted out of poverty in 2020. This is why we felt it important to tell the story of poverty alleviation in China,” said Chai. She feels glad and honored to have been there to document this historic transition and culmination of this massive struggle.

Chai Hongfang is chatting with villagers who have built a close relationship with her during four years of shooting.

A Condensed Slice of War on Poverty

“It is a documentary about poverty alleviation that is shot with proper filmmaking techniques. The production team was stationed in Shawa Village for more than 1,000 days and nights, recording and witnessing its step-by-step, massive changes. The director tells the story of poverty alleviation in China to the world with warmth and cohesive narration, which makes it a special documentary and sincere effort,” said Zheng Yi, director of Nujiang Prefecture’s publicity department, heaping praise on it.

Shawa Village is located on the Biluo Snow Mountain on the east side of Nujiang Grand Canyon. Before 2018, it was almost isolated from the world, being far away from cities and having no access to roads and the Internet. There are more than 800 people in 228 households in the village. The majority of them were poor, with a per capita annual income of less than RMB 3,000.

In the documentary, we can see that the director uses a simple and concise style of narration to produce fresh and lively characters. Chai hopes that this work “conveys things silently” and conveys hope and power with a warm narration.

With the development of the film and the unfolding of the narrative structure, we will see those touching and soul-stirring stories: Because of the difficult mountain path, it took more than half a day for Po Luo to carry his refrigerator to be repaired down the mountain; Li Jianhua could only carry 20 chickens on his shoulders every time he went down the mountain to sell them; Li Jianhua’s wife had a sudden illness at night, and had to wait until dawn to be carried down the mountain to the hospital for treatment. Also, as there was a lack of pre-school education for kids in the village, Zhu Yun, a member of the military division stationed in the village, temporarily served as a kindergarten teacher.

“Lack of access to roads, limited medical care, and limited access to education, are, in fact, a real predicament many poor mountain villagers found themselves in. Our key task of poverty alleviation is to solve these problems in reality, and generally enhance the people’s sense of happiness, sense of gain, and sense of security. Our lens record the changes in the daily life of these ordinary people. These are lucid and vivid images of the Nujiang ethnic minority people in a fast changing era,” said Chai.

As portrayed in the documentary, we can see that with the construction of the road, Po Luo bought a tractor for doing transportation business and also opened a small shop in the village; Li Jianhua has expanded his chicken farming scale by adopting a scientific breeding method; Laba and other children of the village appear on the stage of China Central Television; thanks to a relocation program for poverty alleviation, Li Xiao’er, the leader of a villagers’ group, and some other villagers has resettled in an urban area to live a modern life.