I have spent several Lunar New Years in China. Each time was an experience that left me with a warm, glowing memory.

Visitors throng the temple fair at the Ditan Park of Beijing during the Spring Festival period in 2019.

Beginning in the 1980s, I have spent several Lunar New Years in China. Each time was an experience that left me with a warm, glowing memory. To an Italian, the Chinese New Year recalls the traditions of the home. It is above all the family dinner fiesta. On New Year’s Eve, young Italians, however, prefer to hang out with their friends, dancing in public ball rooms or in the city square until the first light of the new year.

I remember landing in a snow-white Beijing on the morning of my first Lunar New Year’s Eve in China in 1980 after a 20-hour flight from the heart of Europe via Karachi. On my way to the downtown area, Beijing’s cityscape flashed by like sequences from a classic black and white film noir. Beijing had yet to be streamlined by modernity. The Beijing Hotel on Chang’an Avenue was its tallest building.

I had an extraordinary view from my room on the eighth floor that faced the street. It had stopped snowing, so my panorama view embraced the whole southern part of the city. I remembered the greens of summer, when Beijing was submerged in acacia foliage above which only the yellow roofs of the Forbidden City were visible. Against the snow, the texture of bare trees on its surrounding gray hutongs as far as the eye could see appeared as an embroidery. Over that white and gray expanse rose in the distance the roofs of Dongbianmen and the Temple of Heaven, both of which are obscured by foliage during the summer.

The new moon on the evening of the following day signified the Lunar New Year, also known as Chunjie, or Spring Festival. Wangfujing Street, which begins at the northeast corner of the Beijing Hotel, was more crowded than I had ever seen it. This might be expected of the capital’s main high-end snack and shopping street, but the human river pouring along it proved that Deng Xiaoping’s recently initiated reforms were generating cash in people’s pockets.

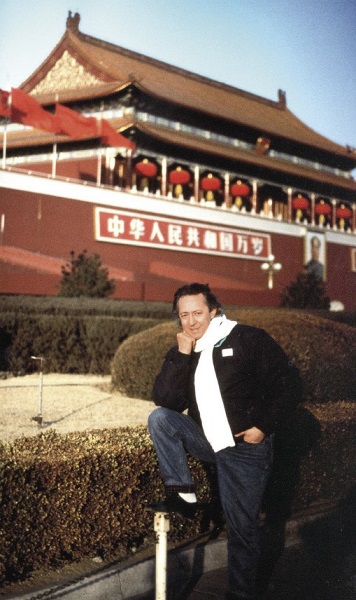

The author Adriano Màdaro at the Tian’anmen Square during his Chinese New Year visit of Beijing in the 1980s.

The happiness of the Beijingers was palpable. I got caught up in their enthusiasm for shopping, and joy at finding so many goods that only a couple of years earlier were beyond imagination. Tossed in the middle of that human course, mainly still dressed in New China’s traditional blue, gray or black shades, yet bursting with a new happiness, I felt a part of my personal, intensely human Beijing, aware that in a few years everything would change profoundly.

But this New Year wrought vengeance on past privations. That seemingly liquid gold crescent moon suspended in an immense, cloudless sky was a good omen not only for that year, but for those to come. China had begun to open up to the world, and also to the challenges of globalization.

At the corner of Golden Fish Hutong, amid the mighty throngs lined up at the theater box office, was a company of extravagantly, red-silk clad musicians and actors bent on luring customers. Rather than their spiel, it was the vibrant red of their garments that attracted customers. Red, as we know, is the color of happiness in China. It is consequently featured in all aspects of Lunar New Year’s Eve rituals, like affixing on door posts calligraphic spring couplets expressing good wishes for the new year on strips of red paper.

Restaurant tables were besieged with entire families whose homes were in the countryside. The minute I fought my way into a small restaurant that I’d heard excelled in the delicacies of traditional Chinese cuisine, a distinguished, bespectacled elder with a white beard waved me over to his table with his chopsticks. It clearly troubled him to see a stranger sitting alone on New Year’s Eve. I thanked him but demurred, because he was celebrating with his family, and besides that, there was no room at the table. But he insisted, telling his family to squeeze together to make room for me. The main dish was jiaozi, followed by famous spring rolls (chunjuan), and the obligatory noodles (miantiao), which is often a fixture for a festive dinner because of its auspicious cultural connotation for long life. There followed stewed, caramelized carp, soft pork belly in sweet sauce, spicy chicken, vegetables, and in conclusion, the highly anticipated glutinous rice cakes (niangao), along with plentiful ganbei (bottom up) to glasses of fiery Maotai – the scalding liquor of Guizhou.

The firecrackers and firework displays outperformed any Neapolitan Piedigrotta I have seen. After all, gunpowder is an ancient Chinese invention, so the skies on the night of my first Beijing Lunar New Year exploded in its vibrant hues until dawn, and beyond. The euphoria of a people anticipating with confidence and enthusiasm the best of times to come was, on that distant night, a truly auspicious omen. In my heart I felt certain that the Chinese people would face and overcome whatever difficulties may beset them.

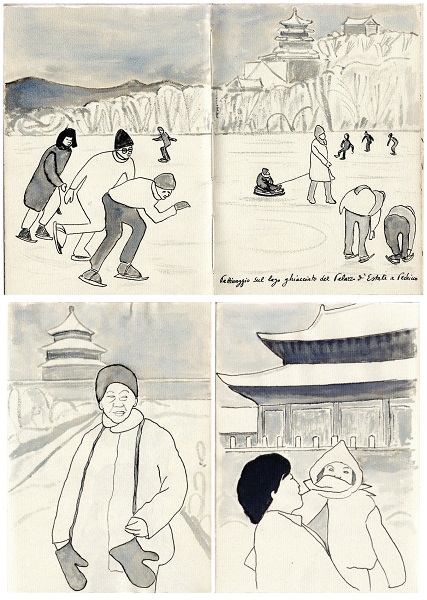

The author Adriano Màdaro draws the three sketches during his first Chinese New Year stay in Beijing in 1980, respectively about people skating on the Kunming Lake at the Summer Palace, a man at the Temple of Heaven, and a mom holding her child in the Forbidden City.

I took a wander through the large imperial parks on Lunar New Year’s Day to celebrate with the people the year that had just begun. Crowds gathered in the Ritan (Temple of the Sun) and Ditan (Temple of Earth), and Tiantan (Temple of Heaven) parks. Every 10 steps there were snack shops, improvised tea houses, candy spinners, noodle makers exhibiting their skill in producing hand-pulled noodle, storytellers, acrobats, illusionists, falconers, men strong enough to burst chains merely by inflating their chests, professionals at Chinese caligraphy, portrait painters, farmers selling kites and bamboo toys, and figurines of colored rice paste modeled on the spot, opera singers, musicians ... it was a heaving, unending cornucopia of wonder. It seemed that old Beijing, the much-mentioned Lao Beijing, its traditions and sound precepts, had reappeared.

I experienced that festive atmosphere amidst the kindest of people, offering their courtesy, smiles, and congeniality, in a dialogue, although limited by language differences, was warm and friendly. The joyfulness of the children was a main element of that celebration, its fundamental ethos one of innocence and the soul’s willingness to luxuriate in simple, familiar things, like daily food items transformed into a banquet delicacy. I truly experienced in my heart the humanity of an ancient people who have, over the centuries, accumulated such a wealth of wisdom and culture. The Lunar New Year is the most important holiday, because to rural dwellers the movements of the Moon signify the renewal of life. For an ancient civilization like China’s, the seasons and rhythms of the Earth constitute the supreme celestial benevolence.

I hope from the bottom of my heart that China will continue to safeguard its traditions while aspiring to further scientific advances for the benefit of all humanity. And I also hope that after the pandemic’s severe lesson, the planet will recommence being everyone’s home, where we will all engage in the protection of nature, and in the communion of traditions that keep our planet humane. May the Chinese Lunar New Year – the Spring Festival itself – be an intangible but precious asset to all men of good will.

Such is the conclusion to which my festive, friendly New Years in China have brought me. Soon the plum, the first tree to bud, will blossom. I see it as a symbol of rebirth, purity, and benevolence; the awareness that every winter blossoms into spring.

ADRIANO MÀDARO is an Italian writer, journalist, and a well-known expert on China. He has published more than 30 books on modern China.