GUNPOWDER was one of the four great inventions of ancient China and is considered the precursor of modern explosives. However, in later times, China lagged far behind Western powers in the development of explosive technologies. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, research and development in this area regained importance.

“Strengthening national defense and avoiding the possibility of being vulnerable to attacks” has always been a dream of Wang Zeshan, a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and a recognized expert on explosives. He has devoted more than 60 years to the related research, and has overcome three globally known difficulties, thus his work has promoted China’s technological advancement in this field. For all his contributions and achievements, he is acclaimed the “King of Explosives.”

Majored in Explosives

Wang was born in 1935 in Jilin Province. At that time, the three provinces of northeast China, namely Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang, were under Japanese colonial rule. The Japanese authorities established the Empire of Manchukuo, a puppet regime with Puyi, the last emperor of the Qing Dynasty, as the ruler, and promoted enslavement education there. However, as a child, Wang’s father constantly told him, “You are Chinese and your country is China.”

Wang Zeshan tutoring his students.

After witnessing the atrocities of the Japanese invaders and internalizing what his father said, Wang harbored from a young age the desire to serve his country. “If you don’t want to be a slave of a foreign conqueror, you must have a solid national defense,” he believes.

Wang graduated from high school in 1954 after the Korean War had just come to an end. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese volunteer soldiers won the victory with obsolete equipment and enormous sacrifices. This left a deep impression on Wang. “None of us wants war, but the world is full of problems. We will be defeated if we fall behind. A nation without a solid national defense is like a nation without doors,” he believes. For this reason, Wang decided to choose an unpopular major – explosives – at the Harbin Institute of Military Engineering (now the Military Engineering Institute of the People’s Liberation Army).

The research on explosives is dangerous but of great importance. In the early years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, both research and production of explosives were extremely behhind the times, relying chiefly on the assistance of the Soviet Union. Following the split of the two sides, the Soviet Union withdrew all their specialists from China, as a result, China’s research on explosives technology landed in a very difficult situation.

At that moment, Wang had just started his career. There was neither external technological help nor any advanced research platform. Nevertheless, these challenging circumstances did not discourage him, but instead inspired him. He devoted himself to building up the field of study starting with basic principles and theoretical systems.

From the 1960s, Wang established the discipline of propellant charging based on the studies of the basic theories of explosives, and integrating the disciplines of gunpowder, cannon, ammunition, and trajectory. At the same time, he discovered the rules of explosives’ composition, structure, and performance, and established the structural-activity relationship of cannons, ammunition, and gunpowder, therefore developing the theories about explosives.

Solving Three Global Difficulties

With the easing of the international situation and the improvement of China’s surrounding environment in the mid-1980s, disposing a large number of obsolete explosives became a major problem facing the international community. In 1985, Wang and his team set out to study how to safely reuse such explosives.

Wang visited many ordnance enterprises and public institutions as well as experimental fields of research institutes in Liaoning, Inner Mongolia and Qinghai. After countless trials over 10 years, Wang led the team in solving key problems and developed solutions for explosive waste in civil products. For this reason, Wang was awarded the first prize of National Award for Science and Technology Progress in 1993.

Wang Zeshan in a chemical laboratory in 1993.

For Wang, the activity of scientific study is endless. The resolution of one problem always means the beginning of another. In 1990, Wang sought to overcome another challenge: energetic materials with low temperature sensitivity.

Gunpowder and explosives are highly sensitive to external temperatures. The triggering parameters of the same type of artillery equipment vary in different regions and seasons. The way to avoid this variation in their performance was an objective that the worldwide armament industry had attempted to achieve for over a century. China has a vast territory and the temperature difference between the extreme north and south, as well as between the winter and summer seasons is large. Therefore, the need to solve this problem was very urgent.

In order to create experimental conditions with great temperature differences, Wang conducted tests in the extreme environments of Inner Mongolia and Qinghai. In winter, the temperature could drop to minus 30 degrees Celsius, the wind with sand and dust made visibility virtually non-existent, causing even the cameras to go blank. But Wang stayed at the testing ground for the whole day, and at night he checked and verified all the various experimental data obtained during the day to locate whether there were any loopholes in the experimental process.

After five years of study, Wang managed to invent the propelling charging technology with low temperature sensitivity, established the equivalence relation between burning rate and burning surface, and found new materials that compensated for the effect of temperature. The temperature sensitivity of the pressure in the combustion chamber was reduced from the original 15 percent to less than three percent, and the artillery firing power was increased by more than 15 percent. In 1996, Wang won the first prize of National Award for Technological Invention with this technology, a prize that had not been awarded in years.

Having won two national science and technology awards, Wang went on to “conquer another peak.” “While the older generation of scientists were still pursuing their goals, and their scientific attitude remains rigorous, I was just in my 60s, how could I stop?” said Wang, who then turned his attention towards identical module charging – the technology of universal application.

Artillery is known as the “god of warfare.” To strike targets in different distances, it needs to switch between different charging modes, and the operation is cumbersome and time-consuming. Previously, scientists from the U.K., the U.S., Germany, France, and Italy had conducted joint research and attempted to use the same unit module to achieve strikes on near and far targets through different combinations of modules. But due to the inability to achieve a breakthrough in the technological bottlenecks, the study was finally terminated after spending a huge amount of money and going on for many years.

“The needs of the country are the direction of my research,” said Wang. With decades of research in the field of long-range and module launch charges, Wang felt that he needed to tackle the challenge again.

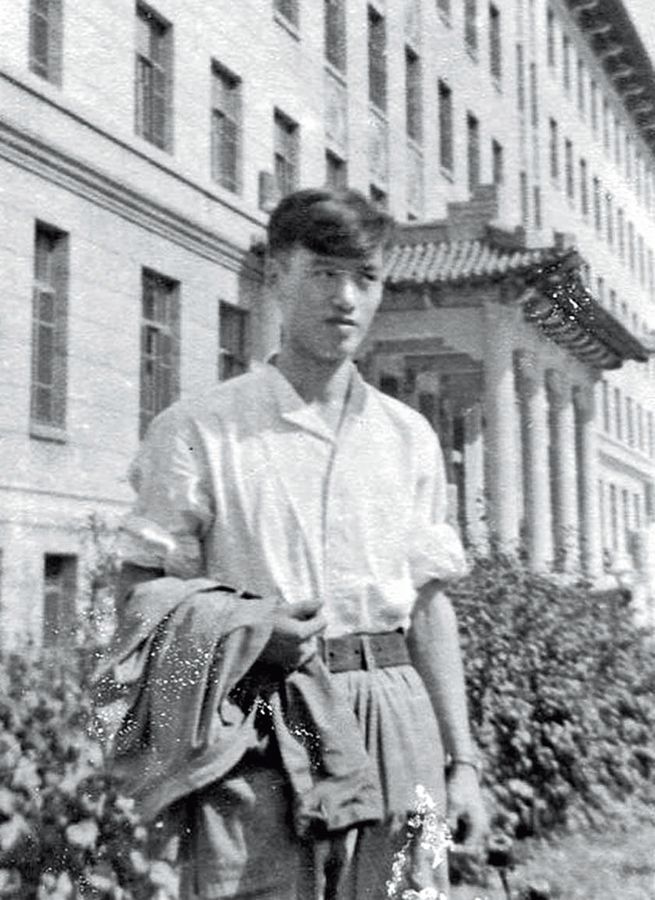

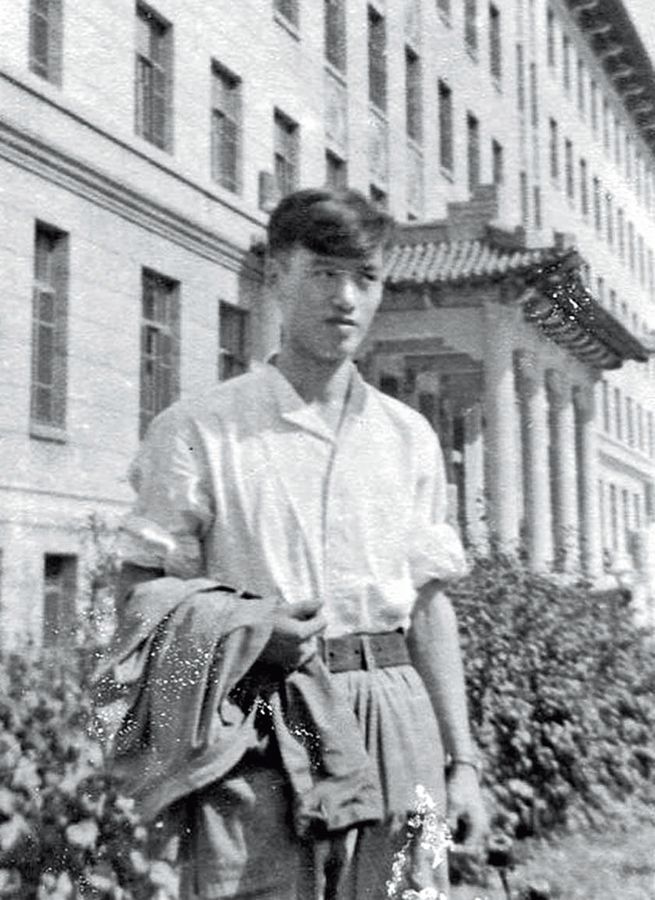

Wang Zeshan studying at the Harbin Institute of Military Engineering in 1956.

With persistent efforts for more than 20 years, Wang finally developed the new charging technology and ballistic theory. Following the application of this technology, Chinese artillery has increased its firing range by more than 20 percent, and the maximum launch overload has been effectively reduced by more than 25 percent. Not only does its ballistic performance exceed that of similar guns in other countries, but also reduces the flames, smoke, and harmful gases generated by the burning of gunpowder, reducing the harm to operators and the environment. Currently, this technology has been widely used in the development and production of various types of weapons and equipment in China.

Due to his outstanding contributions in the field of explosives, Wang, at the age of 82, won the State Preeminent Science and Technology Award in 2017, the highest award in that sector in China. It is granted annually to no more than two people, and the Chinese President signs and presents the certificates and the prize money personally. Up to January 2017, the prize had been awarded to just 27 experts.

Science as a Guide

Many wonder why Wang has always been able to maintain such a spirit of innovation. “My secret is allowing science to guide my research,” said Wang. He explains that this approach involves three aspects: scientific spirit, scientific attitude, and scientific methods.

“In research, you must first have a scientific spirit; that is, dare to go further and strive for excellence,” he said.

According to Wang, a true scientific attitude is not to take shortcuts in scientific research. To achieve objectives, one has to persevere and never waver in the face of difficulties.

Wang has his own understanding of the scientific methods. After decades of research, Wang often uses divergent thinking to explore solutions to problems. He acknowledges frankly that he doesn’t like to follow the footprints of others, but instead thinks out of the box.

Wang especially values time. “He seems like an indefatigable being,” is what those who know him describe him as. If there is no special task requiring his time, Wang goes to bed at 9:30 in the evening and gets up to work at 2 or 3 o’clock. “There is often a lot of hustle and bustle during the daytime, but the early hours are quiet, ideal for thinking,” he said.

Wang’s life has become increasingly busy and he feels that time is insufficient for him. “There are many things that I haven’t done yet,” said Wang. Even when waiting for transportation, he pulls out a folder in which he keeps information and data related to the problem he is pondering about. “I’ll try my best to do whatever hasn’t been done or hasn’t been successfully done abroad. As researching explosives is already part of my life, I’m just looking to do it well.”

Wang is now 84 years old and his team has a new direction to proceed in, and they are ready to overcome any new technological challenge.