Tomb Figures Full of Life

By staff reporter XING WEN

|

|

|

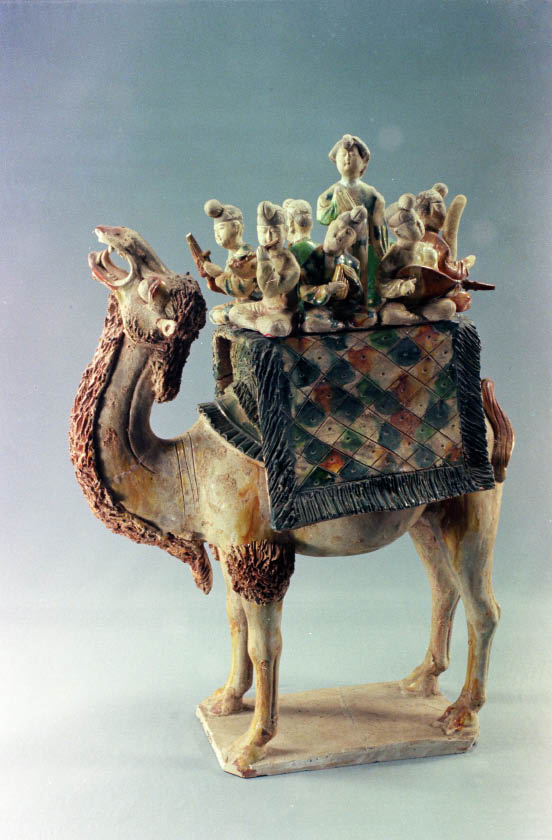

Camel figurines are common and they often carry a few musicians on their backs. |

IN the early 20th century when a railway was being built in Luoyang, Henan Province, large quantities of pottery shards were excavated from a number of ancient tombs that had been exposed during the construction work. The fragments were glazed in three colors – yellow, green and white. A few years later, utensils glazed in the same three colors and unmistakably identical style were unearthed in Xi'an, Shaanxi Province.

This type of earthenware was named Tang tri-color (tangsancai), since they were all discovered in tombs of the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

Chinese pottery skills date back at least 10 millennia. In the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), people found that minerals could be used as pigments. They made glaze with hematite or manganese oxide and fired the pots to make single-color works.

Under the Tang Dynasty, China was one of the most prosperous empires in the world. The economy and culture developed rapidly, as did technology in almost every field. Craftsmen acquired vast knowledge of the properties of metallic oxides and improved the techniques of pottery production. Based on skills handed down from the Han Dynasty, the Tang craftsmen added more lead to the pigments and gave the pottery two kiln firings. In this way, the glazes melted and commingled, forming a multi-colored coating.

Most Tang tri-color glazed earthenware was handmade in Xi'an and Luoyang – the capitals of the Tang Dynasty in different periods. Archeological research shows that burial practice then was extremely lavish. The upper class decorated their tombs with splendid murals and packed the space with exquisite objects including this kind of earthenware, whereas common people could afford only a few simple and crude clay objects.

However, the unending battles in the last years of the Tang Dynasty produced a gradual decline in tangsancai pottery owing to the short supply of pigments and other materials, and a falling demand for such crafts. In the succeeding Song Dynasty (960-1279), ceramic techniques were further developed and tangsancai pottery gave way to porcelains of a more fine and delicate texture. So the technique fell into oblivion. For that reason, those Tang pieces that have survived are limited in number and very precious.

Around 1920, some artisans in a village near Luoyang managed to repair the pottery fragments. With the gradual improvement of their skills, they tried to revive the lost craftsmanship. One of them, Gao Liangtian, building on what he had learned in pottery repair, was the first to succeed in resurrecting tangsancai. His skills were passed on in the village, where most residents today earn their living through making tri-color glazed pottery.

This work calls for high skills in clay modeling, painting and firing.

The base is made of kaolin clay, which is shaped into a multiplicity of forms – human and animal figures and different utensils – before being dried. The dried but unglazed base is kiln fired at between 1,000°C and 1,100°C. Craftsmen then use various metallic elements to create the glaze colors: the green is made of copper oxide and quartzite; the white is the product of zinc oxide and lead powder; and the yellow comes from a mixture of iron oxide and quartz.

The glaze concoctions are then applied to the surface of the single-fired body, after which the item is fired again at between 800°C and 900°C. The cooler second firing causes no change in shape but is hot enough to melt the pigments. In the hot kiln the glazes spread and run, mingling with each other and forming a variegated and unique patina.

|