| Architecture with Chinese Characteristics

By staff reporter VAUGHAN WINTERBOTTOM

IF architecture is frozen music, as German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once said, then China’s premier cities are filled with towering symphonies.

Up-and-coming metropolises seem intent on instilling batophobia – the fear of being near tall objects – in their residents, and China’s first-tier cities are no exception. The current construction boom in the country kicked off around the turn of the millennium, and since then, the functionalist, swimming pool-moulds that were architectural de rigueur for decades on the mainland have slowly sunk into the shadows of skyscrapers, with each new corporate pinnacle striving to be taller and bolder than the last.

To some extent, the scraper race continues today. At 600 meters, the twisting Canton Tower in Guangzhou was the tallest tower in the world when it was opened in September 2010. (The Tokyo Skytree, at 634 meters, usurped the title in March 2011.) And the Shanghai Tower, which will reach 632 meters when completed in 2014, will be the second tallest building in the world, outreached only by the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

But closer to street level, China’s cityscapes are also changing in less ostentatious ways. Leading architects working in the country are shifting away from extravagant showpieces and looking toward sustainable, mixed-use architectural works that draw on both Western and Chinese aesthetics and allow more room for civic spaces. The aim: to create pleasant, green and inspiring urban backdrops for the one billion Chinese expected to be living and working in the country’s cities by 2025.

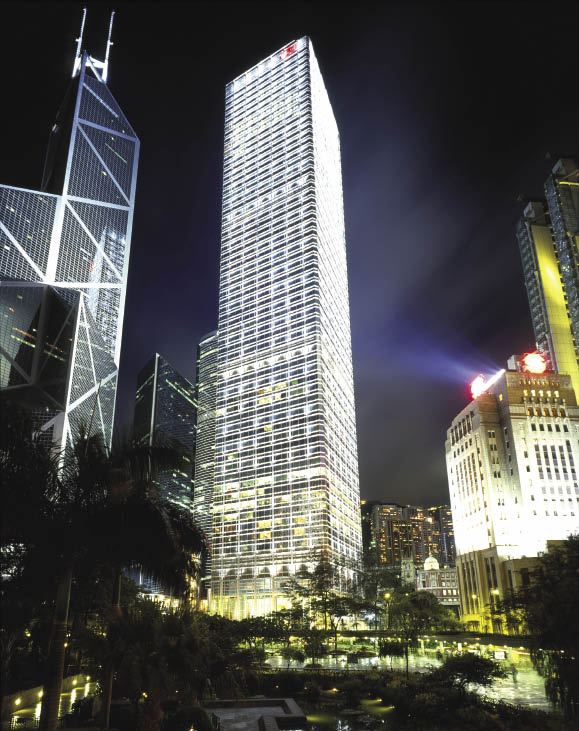

To learn more about these changes I met with Leo A Daly III, chairman of Leo A Daly, an architecture, engineering, interiors, and planning firm headquartered in Omaha, Nebraska. Daly boasts an impeccable oeuvre in China that includes the Shenzhen Excellence Century Center, the Haitong Securities Building in Shanghai and the Cheung Kong Center in Hong Kong.

“My father and I started working in China through a Hong Kong office in 1967, and since then there have been so many paradigm shifts in the domestic industry that we’ve lost count,” Daly tells me over an espresso on the 68th floor of Shangri La’s World Summit Wing. The hotel occupies the top 16 floors of the 330-meter-tall China World Tower, Beijing’s tallest building. From our vantage point, steel and glass mountains rise high above rivers of bitumen; the dramatic geography of the city’s central business district throws weight behind Daly’s words.

|

| Daly's Cheung Kong Center is located at the heart of Hong Kong's iconic skyline. |

|