| The Book of Changes

Clarifying human affairs by understanding the pattern of the heavens

By WEN HAIMING

FOR ordinary Chinese, the Book of Changes (Zhouyi 周易) is usually taken as a mystical book for fortune-telling. But it is actually the fundamental resource of Chinese philosophy, and it is Zhouyi that shapes the unique Chinese philosophical awareness. In other words, the ultimate origin of Chinese philosophical awareness is rooted in the exclusive thinking paradigm involved in the Zhouyi philosophical system.

Philosophically, Zhouyi is a book written to reveal the patterns (dao 道, literally means "the way") of things changing between the heavens and earth, which in ancient Chinese refers to the world as a whole. It aims to help things flourish and facilitate human affairs. The authors of the Zhouyi imitated the myriad changing things in the cosmos by applying a structure of hexagrams and images based on the observation of natural changes over a period of 1,500 years, from 2,000 BC to 500 BC.

Basic Knowledge

Yi in the Zhouyi has three meanings: mutability; immutability; ease and simplicity. Mutability or transforming indicates that everything is forever changing and the Zhouyi is a book about the philosophy of change. Immutability accounts for the relatively unchanged dao that exists, though things are always flowing. Both the dao of nature and human affairs might have a character of immutability, just like the patterns in handling things and the principle of moving things. The third connotation of yi is ease and simplicity because it is very easy to understand the dao of Zhouyi, and it is very simple to put the dao into practice. The Zhouyi is composed of the following elements: numbers, images, trigrams and hexagrams and words.

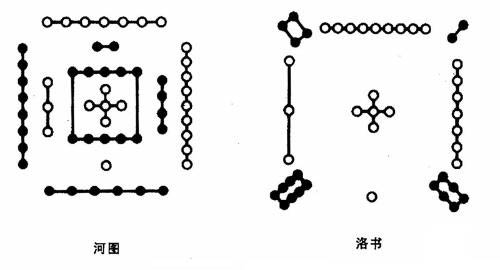

We use numbers in our everyday lives, such as ID numbers, phone numbers, etc. Ancient Chinese realized the importance of numbers even before their culture and civilization started. The basis of the Zhouyi is its unique philosophy of numbers. In the ancient legend, the dragon-horse jumped out of the Yellow River with a map (He-tu) on its back, and the divine tortoise floated on the Luo River with a chart (Luo-shu) on its back. When the ancient sage Fu Xi (said to be the first of the Three Sovereigns of ancient China) saw them, he created the eight trigrams according to the philosophy of number in the He-tu and Luo-shu. He-tu is formed by numbers one to ten, and Luo-shu is formed by numbers one to nine. The philosophy of numbering displays rigor and efficiency in this philosophical reasoning of ancient Chinese people, though it lacks the structure of Western analytical philosophy. The application of numbers in the Zhouyi system is involved in its method of divination, calculating a tri/hexagram over intricate steps.

|

| He-tu and Luo-shu |

Whenever people use the Zhouyi, they have to think through images, which can be regarded as a special "language" of the Zhouyi. The image is the basis for constructing the Zhouyi into a book. In Chinese, xiang 象 (image) means to imitate and represent. Each trigram represents a kind of thing or event in the universe. The ancients considered there were eight kinds of basic things in the world and characterized them as the heavens, earth, thunder, wind, water, fire, mountains, and lakes. Each is respectively symbolized by a trigram: (Qian 乾), (Kun 坤), (Zhen 震), (Xun 巽), (Kan 坎), (Li 离), (Gen 艮), (Dui 兑).

For ancient Chinese, the whole universe was composed of qi 气 which is not just material, but also psychological, so qi can be regarded as psycho-material force. The basic component of the trigrams is the undivided line "–", i.e., yang/strong line or broken line "- -", i.e., yin/soft line. The yang line represents yangqi as a leading power, and the yin line represents yinqi as a following power. Every changing phenomenon is formed through the communication of yinqi and yangqi. In other words, changes between two opposite powers produce the myriad things.

As a book, the words of the Zhouyi have two sections: one is the Classic (jing 经) and the other is the Commentaries (zhuan 传). It is said that the Classic was created by both Fu Xi and King Wen of Zhou (named Ji Chang, founder of the Zhou Dynasty). The Classic is less than 5,000 words, and it is ancient, obscure, succinct and profound. It explains each line of each hexagram. Over time, numerous commentaries have been developed for the Classic alone. The Zhouyi is a book made through the process of observing images and attaching words.

Without the Great Appendix, it is very difficult for us to understand the Zhouyi today. It was said that Confucius was the author of the Great Appendix. Confucius read Zhouyi diligently in his late years to the extent that the leather ties that bound the bamboo slips together broke several times. He was afraid that people after him might be unable to understand the meaning of the Zhouyi, so he compiled the ten articles of the Great Appendix, which are called "Ten Wings" to accompany the Classic.

|