| Coupling and Uncoupling Chinese Style

By staff reporter QIAO TIANBI

DECADES ago, in the era of the "cultural revolution" (1966-1976), love and marriage bore a heavy political burden; the little red book (Quotations of Chairman Mao) was presented in place of a wedding band, or generally served as a token of love and engagement. Imagine how outlandish it seems to young people today to read love letters that pine: "I hope you can arrange your work, study and life well, so as to sustain your ideals and revolutionary zeal, and not degrade into an uncouth and lowly person." But such sentiments were typical 40 years ago in decent young men and women, who often delivered revolutionary pep talks instead of whispering "sweet nothings."

|

|

|

Changing fashions in wedding gowns and attire are depicted in a Chongqing photo exhibition. Cnsphoto |

The 1950s: Untying the Knot

Marriages were mostly arranged by parents in the days before the founding of the PRC in 1949, often with the help of go-betweens. Many newlyweds saw their better half for the first time on the night of the wedding. Polygamy was also widely practiced in these times, but in 1950 New China brought down its first legal instrument to establish monogamy and protect freedom of choice in partnering – The Marriage Law.

The law stipulated: "In cases wherein one party insists on a divorce, a permit shall be granted after mediation efforts by the relevant people's government and judicial department fail." The blowback was a surge of divorce suits in the early 1950s. According to research conducted by Yue Qingping, a professor at Peking University, in some places divorce cases accounted for as much as 90 percent of all marital legalities. Furthermore, records show that by the middle of 1952 New China handled a total of 993,000 divorce cases, most of them involving arranged unions.

In the decade following, the new marriage freedoms and a more equitable family life style gradually prevailed as the norm in China. However, mainstream ideology still encouraged young people to subordinate their personal affairs to the needs and interests of the nation, and young people became secretive and reticent about their romances. Zhang Yongchuan, academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, was a student at Central China Engineering Institute in the mid-1950s, and his wife was his schoolmate at the time. He recalled that he could only manage dates with his lover at the school balls, and behave towards her much as he would to any other schoolmate. Campus romance was forbidden, and violators were expelled.

The 1960s and 1970s: Married to the Revolution

Not long after the Chinese broke from the shackles of the feudal tradition, love and marriage became rooted in the political drama that followed. Now they had the choice, the criteria young men and women used to assess a future spouse were "redness" and "expertise" – a sound and spotless political background as well as special working skills. Love letters of the period were also full of revolutionary vernaculars. Some families even broke up under political pressures. For example, a wife from a worker's family would divorce her husband from a capitalist family in order to cut any connection with adverse political ties, thus protecting her children from discrimination by association. Sociologist Wu Changzhen summarized, "Couples divorced in the 1950s mainly to shake off arranged marriages, in the 60s to sever unwanted class ties, and in the 1970s to get away from the wrong political factions."

Sex was insignificant in choosing a marriage partner during that period. For most people, "sex" simply meant continuity of the family line, and carnal knowledge wasn't widespread. Extramarital sex was an ethical crime of sorts, met with severe punishment. One of the earliest post-"cultural revolution" films, Corner Left Unnoticed by Love (1981), represented such a period: in the plot a young man and woman in the countryside fall in love, and one thing leads to another. Discovered by villagers, the woman commits suicide and the man is imprisoned as a rapist. The movie won the 1982 Golden Rooster, the highest film accolade in China.

The 1980s and 1990s: Secret and Illicit Loves

|

|

|

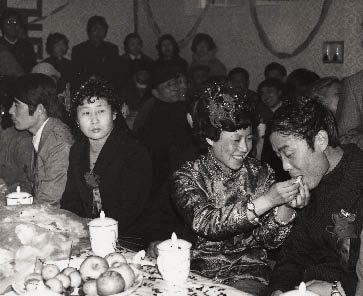

Group weddings like the one shown here were just the thing for city folks in the late 1980s. Xinhua |

The movie Love on Lushan Mountain (1980) broke the taboo against kissing that arose during the "cultural revolution." The scene rekindled the nation's passion for liberty in affairs of the heart, and the first to jump on the bandwagon were the college students, who worshipped love as the point of existence. Though courting on campus was still forbidden at the time, many students conducted romances under the radar, finding reasons to study together and hiding their love letters in books. When night fell, they stole out to find quiet and private spots for their trysts.

The Marriage Law was revised for the first time in 1980, and certain legal requirements for divorce were dropped. Correspondingly, beginning in the 1980s, China's divorce rate continued to climb – from 341,000 pairs in 1980, to 800,000 pairs in 1990, and to 1.2 million pairs in 2000, according to Professor Wu Changzhen. Though people had more freedom to legally split from a spouse, ethical adjudication still held sway at the time. Professor Wu cited a case he came across where a teacher had a long-term extramarital affair going and appealed eight times to the local court for a divorce; each time he was rejected for "lack of evidence proving the emotional breakdown of the couple."

In 1983, China enacted the first marriage law that dealt with Chinese-foreign couples. At the time many people resorted to unions as a way to go abroad, and most cases involved young Chinese women and much older foreign men. "An age difference of 25 years was commonplace," recalled Zhao Xiuying, who worked for 22 years as a clerk at the Chinese-foreign marriage registration office of the Shanghai Municipal Civil Affairs Bureau.

In 1977 when Shanghai came across its first case of international marriage registration, the local civil affairs bureau rejected it until Deng Xiaoping personally intervened. Only a year later the city registered 148 Chinese-foreign marriages, and the figure has topped itself every year since. The registration process was very complicated then, requiring approvals from different government departments, and even references from the workplace and neighborhood committee of the Chinese applicant. It usually took a month before any couple was awarded their marriage license.

|