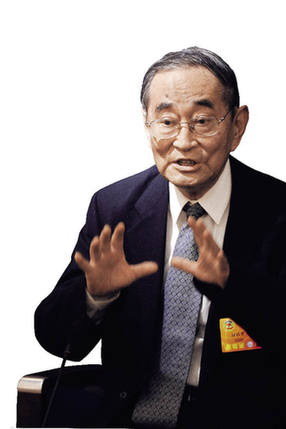

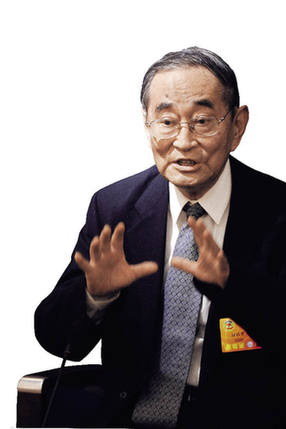

| Just Call Me "Three F Li"

Narrated by LI YINING & collated by staff reporter LIU QIONG

Li Yining is a well-known Chinese economist with an impressive set of responsibilities. Currently he is president of the Market Economy Academy of Peking University, honorary president of the Guanghua School of Management of Peking University (and its doctoral supervisor for work related to national economic policies), member of the Standing Committee of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), and deputy director of the Subcommittee of Economy of CPPCC. Li Yining didn't start out thinking of himself as a "numbers guy." Born in 1930, his earliest career aspirations were to "bring salvation to the people through science" and "rejuvenate the nation through industry."

They used to call me Private Enterprise Li (Li Minying), but I would rather be known as "Three F Li" (Li Sannong). It was by accident that I became an economist. At the very beginning of China's economic reform, I presented the concept of transforming China's economy through shareholding, and suggested that the private sector and the state-owned sector enjoy equal status in the economy. As a participant in economic policymaking in China I have witnessed a lot of changes to the People's Republic. These days I am looking for solutions to problems posed by rural development, or what we know as the "Three F (Sannong)" issue – farmland, farmers and farming.

The Winding Path to Economics

From primary school to middle school, I was partial to literature. I read carefully, over and over, such Chinese classics as A Dream of Red Mansions, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and poetry. I was also moved by the works of foreign authors, such as Balzac, Maupassant, Tolstoy, and Turgenev.

Then as an adolescent, I experienced Japanese aggression, the curse of civil war, and the dire poverty of those years. On the eve of my graduation from high school, the school authorities organized a student visit to a large chemical plant. It was there that I began to realize the importance of chemical fertilizer to strengthening China's agricultural production. That's what inspired my "salvation through science" phase. So on graduation, when I was recommended for immediate admission to Nanking University, I chose the Department of Chemical Engineering without hesitation.

However, when I received the admission notice from the department in February 1949, the political situation had changed. Two months later Nanjing was liberated. Instead of going to college I went to Yuanling in Hunan Province that December to work, first as an accountant for the county's school supply cooperative, and later as a clerk with the county's construction committee. In the summer of 1951, I decided to take the entrance examination for university. For convenience, I asked my former classmate Zhao Huijie, who at that time was studying in the Department of History of Peking University, to sign up for me. He considered several factors in selecting a field and a major for me – my working experience as an accountant, my academic strength in both the arts and science, and the country's needs – before deciding the Department of Economics was the best choice and one where I had some advantages. So the application was filed with the Department of Economics as my first choice. In August, I was admitted into this department and my lifelong academic preoccupation with economic theory and practice began.

Upon graduation in 1955 I didn't leave Peking University, but was engaged for translation and compilation work in the Reference Room of the Department of Economics. At that time, in addition to loaning books and materials to teachers, the Reference Room also undertook collecting, collating, translating and compiling new materials. To me, work is best experienced as total immersion, like putting a fish into water. Facing a wall of texts on economics – Chinese and foreign books, and scores of foreign periodicals – I naturally became familiar with the spectrum of viewpoints on economic management, and translating books and theses on economics was a way to continue my education. Later I served as the main contributor to Economics Information Abroad, a journal run by the Department of Economics of Peking University.

In the late 1970s, a nationwide debate on the maxim "practice is the sole criterion for testing truth" raged for six months. Minds were emancipated, and it became clear there were serious disadvantages to the blind worship of theory. Since then, I balanced my book-learning by participating in China's economic reform, and, I hoped, did my share to contribute to it.

"Shareholding Reformer Li"

It was the spring of 1980 that I suggested shareholding reform for the first time. As an associate professor at the Department of Economics of Peking University, I participated in the Labor and Wage Forum convened jointly by the Research Office of the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Labor Bureau.

In those days, millions of "educated youth" (middle school graduates who were sent to labor in the countryside during the "cultural revolution") had returned to the cities and were demanding the government provide them jobs. At this meeting I suggested one way to solve the problem of unemployment was to have people pool money to run shareholding enterprises, and the enterprises could then expand their operations through issuing stocks. My suggestion got no response, although shareholding had emerged in the countryside by that time.

Certain commune-run enterprises adopted a system of pooling capital, issuing shares and providing dividends. These enterprises developed well, and their operations showed great vitality. Farmers became shareholders through pooling various elements of production and forming rural shareholding cooperative enterprises. These are the rudiments of shareholding. Of course, operations were not always smooth.

Of all those in Chinese economy, the reform of state-owned enterprises turned out to be the hardest nut to crack. In late 1978, China embarked on a drive to ease government control on the management of enterprises and allow them a share of their profits. Enterprises would have greater decision-making power over their operation. But more decision-making freedom alone couldn't fundamentally improve the management of state-owned enterprises. They remained in a quagmire throughout the early 1980s.

Many officials then sought a cure in the contracted responsibility system for cities. They demanded state-owned industrial and commercial enterprises, in the fashion of the nation's farming communities, carry out a management contracting system based on economic performances. Haiyan Shirt Factory, located in a small town in Zhejiang Province, became a shining example of the success of this reform. Bu Xinsheng, director of the factory, learned a lot from linking remuneration to output in rural operations, and introduced the practice in his workshops. With compensation linked to production, a worker's wage was geared to the number of shirts he produced, without a ceiling or floor. But for every defective shirt a worker made, he or she would be fined a sum double the price of the shirt. The saying at that time was "smash the communal pot." This factory was a trail-blazing enterprise, and the "Bu Xinsheng miracle" aroused a sensation nationwide. The gravel road leading to his factory in Wuyuan Town, Haiyan County, was always crowded with curious visitors.

|