|

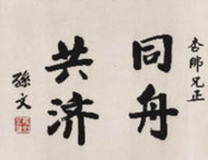

Sun's works incorporated the characteristics of both copybook and stele inscriptions. Some were bold and ambitious, others elegant and gentle, showing his openness of mind. As a whole, his calligraphy was tight in construction, in the style of a master. His spirit took his work to a higher realm, which is regarded as the calligraphic ideal.

|

|

|

Calligraphy by Sun Yat-sen. |

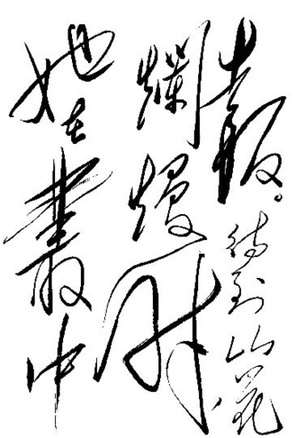

Mao Zedong's appearance on the list of "top 10 calligraphers of the 20th century," according to a poll held in the calligraphy field at the beginning of this century, came as no surprise. His works were appraised as a "compromise between his predecessors' merits, a fusion of masters' styles; handsome like a flying dragon; elegant while bold, pretty while vigorous."

Mao learned to use a writing brush when he went to a private school at the age of eight. He never stopped using this writing tool and was finally regarded as one of its greatest masters. Early on, he studied stele inscriptions like his contemporaries, and later  practiced hard on copybooks, providing a sound basis for the forming of his own style. According to his guards, Mao always spared time to read stele rubbings or to see stele inscriptions himself, even in wartime. His highest achievement was his cursive hand, which was imposing and magnificent, with up and down rhythms – a unique style formed in his middle age. His handwriting was full of energy, but true to regulations, expressing a strong visual beauty. Reading his cursive style handwriting, people immerse themselves in the flow of strokes, slow or fast, dense or not dense. Readers are attracted by the aura his works create, as well as by his presence as the top leader. practiced hard on copybooks, providing a sound basis for the forming of his own style. According to his guards, Mao always spared time to read stele rubbings or to see stele inscriptions himself, even in wartime. His highest achievement was his cursive hand, which was imposing and magnificent, with up and down rhythms – a unique style formed in his middle age. His handwriting was full of energy, but true to regulations, expressing a strong visual beauty. Reading his cursive style handwriting, people immerse themselves in the flow of strokes, slow or fast, dense or not dense. Readers are attracted by the aura his works create, as well as by his presence as the top leader.

Mao revealed his views on calligraphy in conversation. He thought Chinese calligraphy was full of contrasts and balances. "Some characters' construction is big, some small; some are dense, some not; strokes are different in length, boldness and curves; the overall settings are balanced with lines and space, black and white." He said that calligraphers should concern themselves with the strength of characters' strokes – called "bones" in calligraphy – as well as their spirit. "People have faces, bones and spirit, and so do characters," he said. Therefore, when practicing calligraphy, "Simply copy at first, and then imitate the construction and learn the spirit. If you practice long enough, you will find their bones and spirits come out."

Mao created his own style rather than copying ancients, although he paid them great respect. "You need to copy at the beginning, but later focus on improving your own style; you need to learn a certain style, but not be confined by it," he once advised. "Learn from everyone and improve your own handwriting. That is the way to make yourself outstanding."

Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975), long-term leader of the Kuomintang, was also a good calligrapher. His style is characterized by strong bones and precise constructions, as neat and orderly as Zhao Ji's. On the other hand, differences are apparent. Zhao's "slender gold" style featured thin and sturdy strokes, a poised and graceful style that attracted numerous followers. Chiang's was neat in formation and prudent, but not so creative. His handwriting was always even and orderly, irrespective of whether he was in a high or low mood. This shows he was careful about obeying regulations, but restricted by convention.

Mao defeated Chiang in military matters and also outperformed him in calligraphy. Full of energy and ambition, Mao's calligraphy went to the farthest extreme within recognized standards. Regulations set by ancients were recognized and used, but were not an impediment to progress. When writing, he let his feelings carry his brush freely, creating a new calligraphic vista.

Many other modern leaders were also excellent calligraphers, like Zhou Enlai, Zhu De, and Chen Yi. Compared to military, political, or economic affairs, calligraphy is only a kind of pastime. However, just as art embodies a rich culture, it mirrors the characteristics of important figures and their particular leadership abilities.

|