A Second Chance at Life

|

| War criminals in a group discussion. |

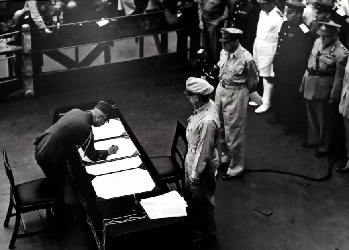

ON August 15, 1945, Japanese Emperor Hirohito broadcast the edict to the Japanese people on Japan’s surrender, thus ending the nation’s war of aggression against its neighbors. On September 2 of the same year, the then foreign minister of Japan signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Japanese government on board the USS Missouri at a special ceremony held by the Allies.

From January 19, 1946 to November 12, 1948, 11 judges each sent by China, the U.S., the U.K., France, the Soviet Union, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Netherlands, India, and the Philippines formed the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which held international trials in Tokyo for Class A war criminals of WWII including Hideki Tojo, Iwane Matsui, and Kenji Doihara. Chinese Judge Mei Ru’ao attended the Tokyo Trial as the chief prosecutor and presiding judge as well as director of China’s legal representative team at the international tribunal.

Moreover, in 1956 a special military court set up by China’s Supreme People’s Court held public trials of Japanese war criminals at home in Shenyang and Taiyuan.

New China Judges

The museum built on the site of the Shenyang Trial of Japanese war criminals is less than three kilometers away from the Liutiaohu (Willow Lake) area where the September 18 Incident happened.

The old layout and furnishings of the tribunal 59 years ago remain on the first floor of the museum. The public seats against the west wall of the hall are always full of visitors, usually watching a video. The 30-minute-long footage is a recording of a public trial of Japanese war criminals.

A tableau in the middle of the hall comprising 51 mannequins recreates the scene of the tribunal pronouncing judgment over the war criminals: All attendees standing, the presiding judge reads out the verdict as the 27 Japanese war criminals in the dock, who had committed monstrous crimes, bow their heads in acknowledgement of their guilt.

From June to July 1956, the special military court under China’s Supreme People’s Court opened the session to try eight war criminals of the Japanese army, including Suzuki Keiku, commander of the 117th regiment of the Japanese army, and 28 war criminals of the puppet Manchukuo regime in Northeast China, including Rokusashi Takebe, who served as chief of the general affairs of Manchukuo.

“It marked the first time that China completely independently held trials of Japanese war criminals for the atrocities committed in Japan’s aggression against China. In contrast to the earlier trial in Nanjing, on this occasion there was no interference by other countries. Considering the international situation after the founding of the PRC, this trial was significant,” said Gao Jian, research director of the 9·18 Historical Museum in Shenyang.

The Allies had previously set up 49 military courts in such places as Nanjing, Hong Kong, and Singapore for trials of class B and C Japanese war criminals. From December 16, 1945 to May 1 of the following year, the government of the Republic of China established 10 military courts in succession, in particular for trials of war criminals, in 10 cities including Beijing, Shenyang, Nanjing, Shanghai, and Taipei.

The museum built at the site of the Shenyang Trial was officially open to the public in May 2014, and affiliated to the 9·18 Historical Museum of Shen-yang. Since its opening, the museum has received nearly 70,000 visitors, according to Song Miao, vice curator.

Xin Yang is a Shenyang native. After watching the trial video in the museum, she said, “It never occurred to me that I would have the chance today to watch a video of a war crimes trial. The scene where, upon seeing the scarred bare back of a Chinese survivor, Suzuki Keiku knelt down and apologized for his crime, left me with mixed feelings.” According to Gao Jian, the museum is amid discussion with the related departments on obtaining authorization to make copies of the footage so as to make the video available to more people.

|

|

|

The surrender took place on board the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945. |

“I Plead Guilty”

The old photos and historical archives collected by the museum present the whole process of bringing war criminals to justice. They are arranged according to the historical sequence of extraditing war criminals to China from the Soviet Union, educating and reforming them in the Fushun war criminal management center, conducting investigations into their crimes, the trials themselves, and sending them back to Japan after serving sentences. Song Miao said, “Visitors are usually impressed with the three sections of the exhibition: war criminals receiving education and reform, war criminals sincerely acknowledging their crimes in trials, and Chinese people’s leniency – no capital punishment and life imprisonment with the maximum term up to 20 years.”

An impressive picture on display shows staff workers of the Fushun war criminal detention center giving meals to war criminals: They queue for food, the first in line smiling happily. The guide of the museum Zhang Lili explained, “At that time food for staff of the Fushun detention center consisited of coarse grain, while the war criminals enjoyed refined grain.”

Then China’s Premier Zhou Enlai gave the instruction to adopt the policy of revolutionary humanitarianism to reform Japanese war criminals. From July 1950 to June 1956, the Fushun war criminal management center regularly provided daily necessities to war criminals, gave them medical checkups, held sports competitions, put on trips to Beijing, and even allowed them to meet their families. The center’s staff educated war criminals via broadcasting, and they were required to compare notes in discussion meetings.

A manuscript by a defense lawyer attracts many visitors at the museum. Song Miao said that the manuscript was a donation by the defense lawyer Lian Xisheng. It was a big challenge to defend criminals who had committed heinous crimes against Chinese people. Lian recalled, “What those Japanese war criminals received was militaristic education. They served and were loyal to the Japanese emperor in the Samurai spirit. They, as individuals, submitted to the state’s will. Therefore, in the pleadings, we tried to ascribe the war crimes to the country, Japan, as acts of state, not totally out of subjective malice.” Lian went on to say, “Such things as personal emotions, national sentiments, and war hostility should not interfere with judicial procedure. As war criminals, the defendants were entitled to legal representation. I defended not only the individuals, but the dignity of law, too.”

After education and reform, Japanese war criminals began to acknowledge their guilt, and repented. When the military court declared the final verdict at the trial of Shigeru Fujita, a former Japanese lieutenant general, the presiding judge asked him what he wanted to say about the judgment. He replied, “I bow my head in acknowledgement of my guilt in front of the court of the Chinese people, who won the war. Flagitious Japanese imperialism turned me into a monstrous beast and made me commit heinous crimes towards Chinese people. However the Chinese government gave me a second chance at life by enlightening me with the truth. I solemnly vow in the just court of the Chinese people to single-mindedly devote the rest of my life to the anti-war peace cause.”

Dedicated to Japan-China Friendship

“The Shenyang Trial was the most successful among the trials of Japanese war criminals, including the Tokyo Trial. Judges and the accused reached consensus in the Shenyang Trial, which confirmed the crimes of aggression in terms of juridical logic,” Gao Jian said. It was also the last trial of Japanese war criminals, during which Japanese war criminals’ attitudes to their crimes formed a striking contrast to those of other war criminals at earlier trials.

During the Tokyo Trial, none of the 28 Class A war criminals pleaded guilty. Even prior to the execution of his capital sentence, Hideki Tojo still held that he had done nothing wrong as Japan’s Prime Minister during the war. At the Nanjing Trial, Tani Hisao, the Japanese commander who directly led the Japanese army during Nanjing Massacre, as well as the two Japanese lieutenants Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda, who staged a monstrous killing contest in 1937, also refused to plead guilty.

Back then, apart from a few war criminals who had committed grave crimes and been held on trial in China and sentenced to a set term, China granted immunity from prosecution to the detained low-level Japanese officers and soldiers who had performed well in reform and reeducation and were found to have committed less serious crimes, and sent them back to Japan. Even those who had been convicted and served sentences in China had all been released and sent back to Japan before March 1964. After release, they formed the Association of Returnees from China, and upheld the tenet of opposing war, maintaining world peace, and promoting Japan-China friendship, thus advancing the two countries’ people-to-people exchanges and cooperation.

In the Shenyang museum, pictures of members of the returnees’ association holding a protest against Japan’s textbook revisions are on display. In addition, pictures of the association members assisting China in holding exhibitions on crimes of Unit 731, a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that undertook lethal human experiments, are also exhibited in 61 Japanese cities. “Now, many members of the association have passed away. So their descendants, together with some sponsors, have established the Continuing the Miracle of Fushun Society so as to carry forward the anti-war spirit of those Japanese soldiers,” Zhang Lili said.