The Final Victory

By staff reporters JIAO FENG, LIU CHENGZI & LI WUZHOU

|

| The main hall of the Western Yunnan Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression Memorial. |

THE Chinese army and people maintained tenacious resistance to Japanese armed aggression, so gradually eroding Japan’s military strength. By 1944, Japanese troops were clearly on the defensive. That year the Chinese army liberated Tengchong County in Yunnan Province from Japanese occupation, so marking the counter-offensive stage of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

Liberation of Tengchong

Tengchong connects with the Yunnan-Burma Road – the sole channel through which the international community could send supplies to the Chinese army after the fall of China’s eastern coast. After the breakout of the Pacific War in 1941, the Japanese army advanced south, intent on attacking and occupying Southeast Asia. To support British troops in the war in Southeast Asia and protect the Yunnan-Burma Road, the China Expeditionary Force, drawn from the country’s crack troops, was formed to fight in Myanmar and India. Some 400,000 Chinese troops fought in this three-year war, almost half of whom were killed or injured. They gave strong support to allied forces fighting the Japanese army in India and Myanmar, and opened international transportation routes into Southwest China, so accelerating the Japanese collapse.

To cut off China’s supply channels, after occupying Myanmar the Japanese army entered China’s Yunnan Province along the Yunnan-Burma Road and attempted to seize the provincial capital of Kunming. Western Yunnan, including Tengchong, thus fell into enemy hands. The Chinese troops kept up a strong resistance to the Japanese advance for years. During spring and summer of 1944, the Chinese army launched counterattacks, and on September 14 liberated the border town of Tengchong.

“Located on the artery of the southwest Silk Road, Tengchong was once outstanding in the regional economy, and hence known as the ‘little Shanghai beyond Mount Gaoligong.’ On September 14, however, when it was liberated, not one house remained standing. A heap of rubble was all that remained of the county,” curator of the Western Yunnan Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression Memorial Yang Suhong said. Tengchong National Martyr Cemetery was built in November 1944 in memory of the Chinese troops who lost their lives in the campaign. “A total of 3,346 Chinese soldiers were buried here, and a further 6,000 died on the Nujiang River en route to Tengchong,” Yang Suhong said.

Surrender Negotiations in Zhijiang

At 11 a.m. on August 21, 1945, Japanese Major General Takeo Imai, on behalf of Yasuji Okamura, commander-in-chief of the Japanese invading armies, arrived at Zhijiang Airfield in Hunan Province with his retinue. The second largest military airfield in the Far East at that time, the airport was a major military base during the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, and remained largely intact at the end of the war.

“The airport was filled with people and raucous voices. The plane carrying Takeo Imai first flew at a low altitude to show respect, and then slowly landed,” reporter on the scene Zhang Yan, later deputy editor-in-chief of China Today, said.

“This was Qiliqiao, where representatives of Japanese troops signed a document of unconditional surrender to the Chinese,” curator of the Memorial Hall of the Victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the Acceptance of the Japanese Surrender Wu Jianhong said, indicating the memorial hall.

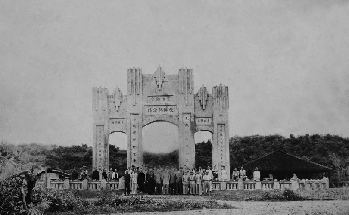

The four-pillar white memorial arch was rebuilt in 2000, based on an old black-and-white photo taken in 1947 when it was first built. “This arch signifies the victory of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, and stands as a historical witness to the world’s victory in the anti-Fascist war,” Wu said.

The hall where the surrender document was signed is a black Western-style bungalow rebuilt from a wartime barrack on one side of the arch. The meeting place inside is not large, but the furnishings are appropriate. A photo of Sun Yat-sen hung on one wall, and on the wall opposite the national flags of China, the U.S., the U.K., and the Soviet Union.

At 4 p.m. on August 21, 1945, Chinese Army Chief of Staff Xiao Yisu, Deputy Chief of Staff Leng Xin and U.S. Brigadier General Haydon Boatner took their seats first, while Takeo Imai and his delegation waited outside. At Xiao’s signal, the Japanese delegation entered the venue, their hats off, and sat down, after standing to attention and bowing. “Military personnel and reporters filled the seats, and the room was packed with people trying to catch a glimpse of the historic moment,” Zhang Yan recalled.

During the ceremony, the Japanese delegation handed over documents showing the Japanese ground, air and navy forces’ order of battle, deployment, division of command and other information. The schedule was also arranged for the respective surrender ceremonies in the 16 areas into which the China Theater was divided, including Nanjing.

According to deputy curator Yang Yu, during their 52 hours in Zhijiang the Japanese delegation accepted specific articles for the unconditional surrender of the 1.28 million Japanese invaders in China. The Zhijiang surrender therefore signifies China’s victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and end of World War II.

“As the envoy of a vanquished country, I was deeply grieved, filled with despair and angst. It signified that we had surrendered with both hands tied,” Takeo Imai wrote in his memoirs.

|

|

Tengchong National Martyr Cemetery, where 3,346 Chinese soldiers are buried. |

Acceptance of Surrender in Nanjing

There is a Western-style auditorium in east Nanjing with a stone tablet at the entrance engraved “former site of the Central Military Academy” and also a plaque that reads “site of the surrender ceremony of the Japanese invading army (China Theater).” A historical photo shows that the facade of the building was decorated with a huge letter “V” for victory for the surrender ceremony.

Inside the hall, the scene of the ceremony 70 years ago, on September 9, 1945, is replicated with lifesize figures, when Saburo Kobayashi handed the Instrument of Surrender signed by Yasuji Okamura to Chinese General He Yingqin.

According to the commentator, the ceremony lasted about 20 minutes. At 8:58 that morning, the Chinese representatives entered and took their seats, followed by the Japanese representatives, who bowed and sat down. The main Japanese representatives had had their heads shaved to show respect. According to a prior arrangement, only Yasuji Okamura could place his hat on the table. The other Japanese representatives put their hats, peaks facing them, on their right knees. Chinese representatives put their hats on the table.

|

|

The memorial arch built in 1947. |

He Yingqin read the credentials presented by Japanese representatives. Xiao Yisu handed the capitulations written in both Chinese and Japanese to Yasuji Okamura, who read and signed them. As it was an unconditional surrender, there was no need for negotiations.

More than 400 people participated in the ceremony, including senior officers from China and the allied countries, as well as reporters.

After the ceremony in Nanjing, the Chinese army accepted the Japanese troops’ surrender in 15 places nationwide, and one in Vietnam. The Japanese military handed over weapons to the Chinese side at 100 designated sites where appointed chief officers accepted their surrender.

|

|

|

Japanese representatives at the surrender ceremony in Zhijiang. |

On October 25, 1945, the surrender ceremony of the Japanese army in Taiwan war zone took place in the Taipei Public Assembly Hall. Having been ruled by Japanese colonists for 50 years, Taiwan finally returned to China.

According to the Chinese Theater’s Acceptance of Surrender Files, more than 128,000 Japanese troops surrendered after Japan’s defeat. Published by Nanjing Publishing Group and the Second Historical Archives of China in August 2015, these files, consisting of 12 volumes, comprise photocopies of the original documents.