By staff reporter JIAO FENG

By staff reporter JIAO FENG

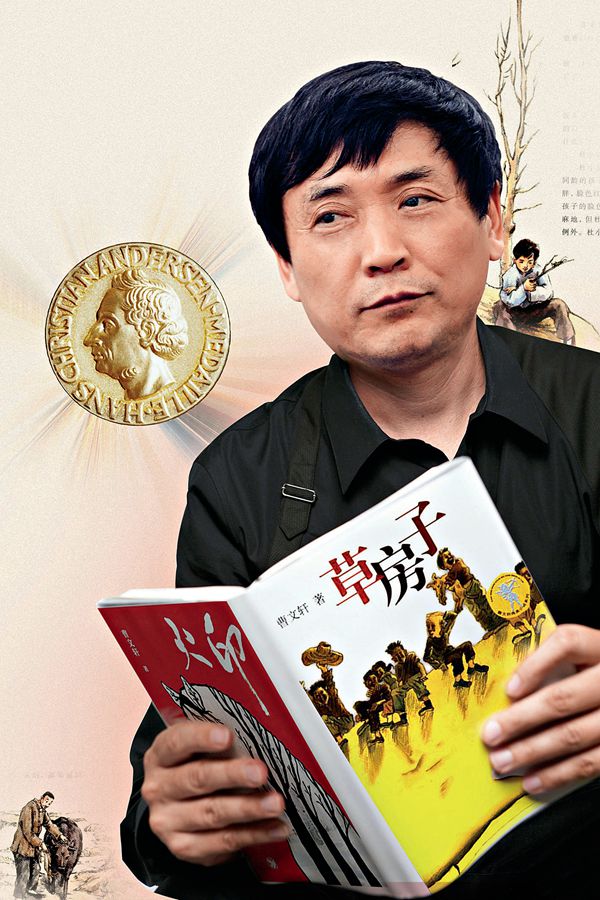

WRITER of children’s fiction Cao Wenxuan became last April the first Chinese author ever to be awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Award, regarded as the Nobel Prize of children’s literature, at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair.

Cao Wenxuan gives a lecture in a primary school in Ningbo of Zhejiang Province on May 10, 2016.

Jury members were unanimous in their choice. In her evaluation of Cao’s works, jury president Patricia Aldana praised Cao’s capacity to pinpoint in poetic style the truly sorrowful instants in children’s lives. Cao is noted in China’s literary circles for his insistence on the purity of literature and emphasis on aestheticism in fiction. The award in some way confirms the artistic quality, influence and appeal of Chinese literature.

Distinct Creation Concept

Since becoming a writer in the 1970s, Cao Wenxuan has always expressed in his works his distinct literary perceptions. In 1983 he published the novella A Cow without Horns. His short story The Old Castle was published in 1985 to great acclaim, and won the Juvenile Literature – a leading Chinese journal on children’s literature – award for the best work of the year. His novel Goats Do Not Eat Heavenly Grass, published in 1991, established Cao’s prominent status in the field of children’s literature. His creativeness took flight in the late 1990s, when he published a trilogy on the theme of children’s growth – The Straw House, The Red Tile, and The Bird. The Gourd Ladle, and Bronze and Sunflower were published in the 2000s.

Cao has over the years consistently laid emphasis on the aesthetics of literature. Whenever telling a story, depicting a person’s character, portraying a social and historical background, or describing a life, he strives to present positive values with which children can identify. They may then comprehensively establish affirmative spiritual values.

Cao believes that as children are the future of a nation, writers of children’s literature are consequently one of the factors that shape what lies ahead. He sees this as “a sacred mission for writers of children’s fiction.” Such a sense of mission explains his pursuit of the creation of books for children that are pure and aesthetically appealing, and his desire to inspire them with a positive attitude.

Cao’s stories portraying how children grow often relate to real-life experiences in his hometown during boyhood. In his eyes, the qualities of childlike innocence and naivete long endure in human nature. This is why he endeavors to convey in his works the universal emotions and spiritual values inherent in it. The stories in his trilogy written in the 1990s can still move readers today. As the world inevitably changes, certain literary works must present the new social reality to children as they grow. However, literature, including children’s fiction, is also expected to capture the inherent depths of human nature that will never change.

In his works, Cao clearly expresses the values through which to judge what is good, evil, beautiful, and despicable. Rather than ambiguous portrayals, he insists on imparting righteous values to young readers in a straightforward way. In his opinion, children do not have the adult capacity to differentiate what is good from evil in the world, and so need guidance. Although such guidance is often apparent in children’s stories, Cao’s works make it clear, for instance, by showing how a kind heart can often lighten an arduous life, and that growing pains intertwine with the wonder of growing up. Firm in his belief that even the most humble life can be narrated in a refined and dignified style, Cao usually sublimates the realities of a hard childhood into his stories.

Having advocated aestheticism over the decades, Cao reached new heights in this regard in his works The Thin Rice and Bronze and Sunflower. The former portrays with subtle poignancy the beautiful southern landscape of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. The strands of pain apparent between the lines testify to his refined and understated writing style. A still deeper sorrow underlies Bronze and Sunflower in spite of its uncompromising descriptions.

Literary critic Professor Xie Mian has noted Cao’s consistency regardless of changing literary trends, in that he unswervingly upholds his faith in literature and earnestly practices what he preaches. “With effort and persistence, the writer that espouses the philosophy of aestheticism is constantly under the self-imposed challenge to attain higher levels,” Xie said. “Today, one such writer has at last harvested due plaudits for his decades of diligent work. Moreover, the Hans Christian Andersen Award could be seen as a prize for Chinese literature as a whole.”

A Soft Fire Smelts Sweetly

Cao’s most recent novel, Dragonfly Eyes, is the story of a Shanghai family. Du Meixi, son of a silk plant owner from Shanghai, meets a French woman whom he marries in Marseilles in 1925. The couple returns to Shanghai during WWII. Mainly about the life of their granddaughter, A Mei, the novel showcases family solidarity from the child’s perspective against the backdrop of the dramatic social changes during the 1960s and 1970s.

Unlike his previous stories, which often take place in the countryside of his hometown in northern Jiangsu Province, Dragonfly Eyes is about life in an exotic and enchanting metropolis. It proves Cao’s ability to tell stories of urban as well as rural life. Despite a different background, Cao’s latest novel sustains his characteristically artistic and authentic style in giving glimpses of humanity amid hardship.

Cao inwardly nursed the plot of Dragonfly Eyes 20 years before eventually writing it. It originates in a moving story a friend told him many years earlier about her family in Shanghai. He was deeply touched, but bided his time before writing it as a novel. Those who know Cao and how he works are aware that it can often take him decades to mentally prepare the structure, plot, and linguistic style of a work. But once he starts, Cao writes at a phenomenal pace.

The actual writing of the 220,000-character novel Dragonfly Eyes took him just two and a half months. The perfectionist Cao then twice revised the work, painstakingly dwelling on every detail. Although seven years passed before the work was completed, Cao’s publisher was aware that Cao is an author that cherishes his reputation and so must be certain any piece of work of his is indeed finished. This is the principle Cao has followed since becoming a writer.

Going Global

Cao was also presented at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair with the newly published Serbian translation of The Straw House. This cooperative project dates back to the Belgrade Book Fair of 2014, which China hosted. A Serbian publisher expressed great interest in the book after Cao mentioned it at the event. The cooperation program ran smoothly and the translation was completed in just a year and a half. So far, Cao’s works have been translated into more than 40 languages and published around the world.

What’s more, Cao is the Chinese writer of children’s fiction that has most frequently cooperated with overseas illustrators. The combination of Chinese stories with international modes of visual expression has charmed young readers throughout the world.

When working with overseas illustrators, publishing houses usually provide them with sketches. After studying them and the basic story lines, illustrators then get to work. Their illustrations can sometimes add greater luster to a book. For example, Cao’s Where Have Xiaoye and His Father Gone tells the story of a motherless boy and his father whom poverty forces to borrow wheat from others. In one illustration, Italian illustrator Eva Montanari pictured the moon as the face of the boy’s mother, although this had not been stipulated. Cao praised this significant touch on Montanari’s part as inspired by imagination and insight.

Zhang Yuntao, deputy editor-in-chief of Daylight Publishing House, believes that cooperation with overseas illustrators can show domestic publishers how their international counterparts complie picture books. “We have realized that illustrations are not simply embellishments but important complements to the story,” Zhang said. Moreover, Chinese publishers often doubt the appeal of local stories for global readers. But through her collaborations with international publishing houses, Zhang has established that overseas publishers are indeed willing to portray the lives of children in other countries to their readers. “Stories with Chinese characteristics are the most valued,” she concluded.

Main Works of Cao Wenxuan

1983: novellas A Cattle without Horns

1985: novel The Old Walls

1988: novellas A Small House Buried in the Snow

1991: novel Goats Do Not Eat Heaven Grass

1997: novel The Straw House

1998: novel The Red Tile Roof

1999: novel The Bird

2003: novel The Thin Rice

2005: novel The Gourd Ladle

2007: novel Dawang Tome: The Amber Tiles

2008: novel Dawang Tome: The Red Lantern

2012: novel Dingding and Dangdang

2014: novel Fenglindu

2015: novel Sear

2016: novel Dragonfly’s Eyes

Cao has also published several collections such as Mist Covered the Old Castle, Dumb Cow, The Blue Countryside, The Green Fence, The Evening Has Come Down Up the Ancestral Temple, A Red Gourd, The Rose Valley, as well as academic works including the researches on China’s literature in the 1980s and the late 20th century, the philosophical interpretation of literature and art, to name but a few.