Face History and Maintain Peace– Interview with Japan’s Former Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama

|

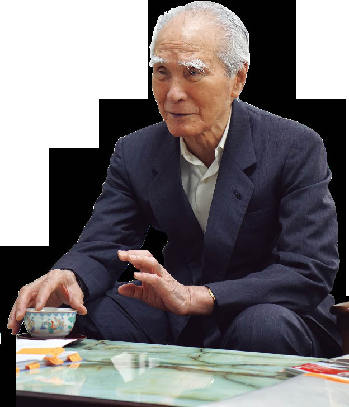

| Japan’s former Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama issued the Murayama Statement in 1995. |

ON August 15, 1995, the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, Japan’s then Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama issued a statement, admitting Japan’s mistakes during the war. In August, 20 years later, the current prime minister, Shinzo Abe, released his own statement. Do his remarks follow the spirit of the Murayama Statement? What is the Murayama Statement’s significance to Japan? Countries such as China and South Korea are paying close attention to these developments.

Against the backdrop of Japan’s lawmakers’ discussions of controversial security bills, Murayama talked about his statement in an interview with the editor-in-chief of People’s China, Wang Zhongyi, and called on the government to abide by Japan’s pacifist constitution. People’s China is a Japanese-language periodical published by China International Publishing Group.

Wang Zhongyi: Extraordinary willpower must have been required for you to release the statement. People might not know much about the difficulties you faced at that time. Could you talk about how the statement took shape?

Mr. Murayama: Japan is a part of Asia, historically and culturally. I believe it cannot survive if it is isolated from the rest of Asia. Japan has a long history of communication and exchanges with China and South Korea, and this has played a pivotal role in the development of Japanese culture. Hence, I sincerely hope that Japan can build international relations that will gain the trust of Asian countries including South Korea and China.

I have traveled around Asia since I assumed office in 1994. At that time, Japan had become a major economy, and its achievements were recognized throughout the world. However, people from other Asian countries still held hostile attitudes towards Japan. Some worried that the country had not seriously reflected on the war, and that it might become dangerous if its military power expanded.

When the Liberal Democratic Party, the Social Democratic Party and the New Party Sakigake formed a coalition government, they submitted a bill to the National Diet to show their reflections on the war and resolve to keep peace. The bill was heavily modified while being deliberated at the House of Representatives. A good number of House members were nevertheless either opposed to the bill or refused to vote. Though finally passed by the lower house, the bill was not discussed as an issue at the House of Councillors. I insisted that the matter not be left as it was. In order to clarify the government’s stand, I decided to express my opinion about the war by giving a statement. But before that, I had been prepared for my cabinet’s resignation if the statement could not be passed during cabinet sessions.

Wang Zhongyi: How did the public react to the statement in Japan, and what comments did you get from neighboring countries?

Mr. Murayama: There were pros and cons in Japan. I myself was strongly blamed. But China and South Korea all spoke highly of the statement and considered it an acknowledgment of historical issues. Later, during my visits to China, I found that the statement was mentioned in welcoming speeches at every place I visited, and I was praised for making a contribution to Japan-China relations. In Japan, subsequent cabinets have all promised the world they would follow the spirit of the statement. Even when certain prime ministers visited the Yasukuni Shrine, which enshrines a dozen Class-A Japanese war criminals, the entailed diplomatic ramifications didn’t escalate into a historical issue, which might be attributed to the inhibitive effect of the statement. Therefore, I believe I did the right thing.

Nevertheless, some people in Japan blamed me. Some could not understand why we needed to apologize over and over again as we had already apologized for the war of aggression. Some even insisted that an apology was unnecessary since “the war of aggression was a defense against the invasion of European countries. When WWII ended, all the colonies were given freedom. It was a war of liberation for the colonies.”

I don’t think we apologize only for the sake of making an apology. The core of the statement was to frankly acknowledge historical facts, reflect on our mistakes and vow never to follow the same old, disastrous road – that is the key to a bright future for Japan.

In the past, there were instances of some Japanese prime ministers individually apologizing to victimized countries during their visits overseas. But a statement approved at the cabinet level means a lot. It’s a shame that the majority of Japanese people did not understand it at that time. To be honest, the statement did not get a favorable response in Japan, and most people paid no heed to it at all. Even today, I’m still asked what the Murayama Statement is about.

|

|

Tomiichi Murayama visited the Museum of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression in Beijing in May 1995, and is shown here at Lugou Bridge. |

Wang Zhongyi: You are the first Japanese prime minister to have visited the Museum of the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. That required great political courage. Could you talk more about that visit?

Mr. Murayama: How do we understand China? What kind of relations should we build with the country? When pondering these questions, we must first learn about China in a comprehensive way. I was involved with the war when I was younger, but I did not go to China and knew nothing about its wartime situation. It’s necessary for me to see the country in person and find out what the war brought to this land.

Wang Zhongyi: Two decades have passed since the Murayama Statement was delivered. What do you think its significance today is, in the context of current Japanese politics and Japan’s relations with its neighbors?

Mr. Murayama: When Prime Minister Shinzo Abe formed his first cabinet, he promised to take on the spirit of the Murayama Statement. However, in his second cabinet, he showed that he would “partly carry on the statement” and intended to deny the war of aggression, which had been discussed in parliament. Although, under pressure, he eventually had to change his wording to “inherit the statement,” his attempt to deny historical facts is known to all. After his questioning of the Murayama Statement, on the eve of the 70th anniversary of the War’s end, Abe was poised to give another speech, which would surely draw world attention to the Murayama Statement.

Wang Zhongyi: Indeed, there is a tendency to deny the Murayama Statement. In which way do you think it will influence Japan?

Mr. Murayama: The pacifist constitution of Japan was enacted based on the country’s catastrophic war experience. In the seven decades since WWII, Japan has never been involved in a war and has adhered to a peaceful development. Asian countries including China and South Korea all think highly of this stance. Most Japanese people now feel uneasy about the government’s right-leaning inclination. I don’t think the people endorse revising the pacifist constitution. In a democratic country like Japan, the sovereignty and the decision-making power belong to the people. Latest polls show that increasingly more Japanese people are opposed to the actions of Abe’s cabinet.

Wang Zhongyi: You and former Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono held a press conference in June, in which you urged the new security bills to be withdrawn. Could you please talk about that?

Mr. Murayama: Most constitutional experts in Japan have pointed out that the new security bills violate the constitution. The National Diet would violate the constitution if it were to submit and deliberate unconstitutional bills. The Prime Minister admitted that the new bills have not been fully accepted by the people. Yet, he intervened in the deliberations and took advantage of his parliamentary majority to force a vote to pass the bill. We cannot allow such wilful acts to happen. Sticking to the pacifist constitution and opposing war are the people’s heartfelt wish, which the parliament should comply with and hence call off the new bills.

Wang Zhongyi: What is your opinion on the current situation between Japan and the world?

Mr. Murayama: The Japanese government is watchful of China issues like territory and China’s Nansha Islands. Besides, it’s concerned about the Korean nuclear issue. Today’s government is exaggerating its crisis awareness, making people believe that Southeast Asia is a hotbed of impending catastrophe.

In my opinion, if the government has a sense of crisis, it is wise to override it through diplomatic efforts. China does not seek hegemony. Its economic development benefits from a peaceful environment. I believe a war is the last thing China wants. Dialogue is the most effective way to remove Japan’s sense of crisis. Arms races, on the contrary, might trigger a war.

Speaking of the U.S., I don’t think it expects a war between Japan and China. Rather, it hopes Japan will be a buffer zone between China and the U.S. It might count on Japan to provide more military assistance in line with its security treaty with Japan.

Wang Zhongyi: How do you evaluate China-Japan relations under the new world order? What kind of relationship should the two sides build?

Mr. Murayama: In his speech at the National Diet in 2008, then Chinese President Hu Jintao pointed out that the bilateral relationship had entered a new strategic and mutually beneficial era, thanks to agreement on the Murayama Statement. Consequently, it is very important to abide by our agreement and prevent disputes. In addition, the economic interdependence between the two countries also demands that the two sides create a favorable diplomatic ethos.

|

|

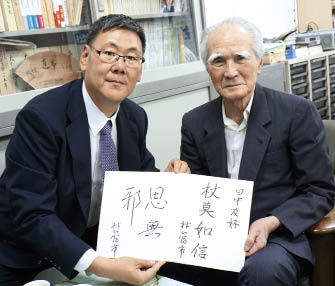

The message Tomiichi Murayama (right) wrote that reads “Japan-China friendship, credibility comes from being true to one’s words,” and “sincerity.” |

Wang Zhongyi: At the commemorative service for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre by Japanese invaders in December 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping pointed out that the commemoration was “not to prolong hatred.” He also noted that “the future of China-Japan relations is in the hands of the two peoples” when he met a group of 3,000 Japanese personnel led by Toshihiro Nikai, chairman of the General Affairs Committee of the Liberal Democratic Party. How would you comment on this?

Mr. Murayama: President Xi’s remarks were welcome. Developing bilateral cooperation and mutual aid will not only benefit the two countries, but also Asia and the world. Even though conflicts are unavoidable, we should strive to resolve disputes through dialogue and work harder to improve bilateral relations.

An Excerpt from the Statement by Prime

Minister Tomiichi Murayama, “On the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the War’s End”

Now, upon this historic occasion of the 50th anniversary of the war’s end, we should bear in mind that we must look into the past to learn from the lessons of history, and ensure that we do not stray from the path to the peace and prosperity of human society in the future.

During a certain period in the not too distant past, Japan, following a mistaken national policy, advanced along the road to war, only to ensnare the Japanese people in a fateful crisis, and, through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations. In the hope that no such mistake be made in the future, I regard, in a spirit of humility, these irrefutable facts of history, and express here once again my feelings of deep remorse and state my heartfelt apology. Allow me also to express my feelings of profound mourning for all victims, both at home and abroad, of that history.

- Face History and Maintain Peace– Interview with Japan’s Former Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama

- Building a New Relationship Model for China and the U.S.

- Upgraded Sino-European Relations Take Shape

- China Strives to Strengthen Global Infrastructure Construction and Build a Harmonious World

- Will China Double Your Salary?