Building a New Relationship Model for China and the U.S.

|

|

|

The author Su Ge. |

THE greatest Tao is the simplest one.” Then Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping thus concisely proposed in 2012 building a “new model of major country relations” for China and the United States. The following year, Xi, as the new Chinese president, met with his U.S. counterpart. Both parties reached a consensus on the principle that should guide their relationship: no conflict, no confrontation, mutual respect, and win-win cooperation.

Resurgence of Negative Elements

Recently, however, the dichotomy in the Sino-U.S. relationship has become more distinct. Its negative elements have come under the spotlight and drawn media attention.

The world has undergone profound changes at the dawn of the 21st century. Increasing globalization and multi-polarization have tilted the power balance between the world’s largest developed country and the developing one. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. entered into two protracted wars. The 2008 financial crisis that originated on Wall Street also dealt a blow to U.S. soft and hard power.

Now, international relations have reached another inflection point. Developed Western countries are on a relative decline, while emerging economies are on the rise in both national strength and international stature. China’s economy is the world’s second largest, and soon expected to reach the top spot. But as an ancient Chinese proverb says, “The tree standing taller than the rest of the forest endures the most wind.”

With the new U.S. policy of pivoting to the East, the “bald eagle” is holding an olive branch in one hand and arrows in the other, supervising the globe in the manner of a world police force. At the end of this century’s first decade, the U.S. looked back at its security strategy and was appalled. It has since decided to drastically modify its policy, pulling out of Iraq and Afghanistan and “rebalancing” to the Asia-Pacific. Its focus on fending off any challenges posed by rising powers increases uncertainties in the Asia-Pacific, rather than calming the region.

As a result, Sino-U.S. relations have wobbled. There has been a shift in the countries’ bilateral trade and economic cooperation and anti-terrorism cooperation, dubbed the “twin engines” of their relationship in the first decade of the 21st century. The restructuring of both economies has led to fresh problems in their trade and economic ties. What’s more, the U.S. has thrown its full weight behind the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), intending to supersede the World Trade Organization (WTO) with these groups. The U.S. has also recalibrated the priorities of its global anti-terrorism strategy.

The “third party factor” also counts. As the policy-making environment in both countries becomes more intricate, factors outside their relationship have come to the fore, meddling in and even hijacking the U.S.’s policy toward China. On the East China Sea and South China Sea issues, the U.S., despite its statements about not taking sides, has shown partiality from time to time, further undermining bilateral ties.

There have been reasonable debates in the Western media on whether Sino-U.S. relations have reached the verge of a crisis or “tipping point.” Some people even claim that the two countries cannot avoid the Thucydides Trap, the dangers two parties face when a rising power rivals a ruling power, as seen in the relationship between Athens and Sparta in 411 B.C.

In the face of these challenges, both countries must reinforce the belief that building a new relationship model is not only essential but also feasible. In fact, one of the reasons why China raised this idea was to avoid the history of rivalry between an incumbent and an emerging power.

Necessity and Feasibility

A line of Chairman Mao Zedong’s poem reads: “Range far your eye on long vistas.” This applies to the Sino-U.S. relationship, which, despite frictions, has been defined by mutual benefit and cooperation. The current situation is not as pessimistic as some media state. The reasons: the basis for cooperation remains solid, the will to cooperate persists and the conditions for cooperation still prevail.

Internationally, as globalization and multi-polarization accelerate, no country can fare well on its own. The international community needs more cooperation. The shared interests of China and the U.S., on both international and regional levels, have increased.

Both countries desire a peaceful and stable international environment. They regularly work together on a broad range of fields concerning peace and development. One example is their close communication and collaboration on the Iran nuclear issue, the nuclear program on the Korean Peninsula, and South Sudan. They have also cooperated in preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, combating terrorism, and crackdowns on cross-border crimes, as well as seeking solutions for regional hot-button issues.

With China’s contribution to the world economic growth standing at 27.8 percent and the U.S.’s at 15.3 percent, the two countries are the leading engines of global economic growth. They are proactive in improving global economic governance by initiating negotiations on the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific. Both countries stand by a free, open international trade system and support free navigation in the high seas.

Their cooperation on multilateral diplomatic platforms – the UN, G20 and APEC – has been fruitful. They have also ramped up efforts to cut emissions, setting an example for global cooperation on climate change, environmental preservation and sustainable development. They, likewise, work together in prevention and control of epidemics such as Ebola.

Bilaterally, building a new relationship model for China and the U.S. is an active exploration for a new mode of action that will enable major powers to work together in the face of globalization.

The confluence of national interests of China and the U.S. provides the impetus for cooperation. Their economic interdependence has been intensifying — last year bilateral trade exceeded US $555.1 billion, or US $100 million every working hour – while two-way investment stocks topped US $120 billion. With their economic ties so tightly interwoven, they are economically in the same boat.

Meanwhile, their citizens are in closer contact. Some 4.3 million people traveled between the two countries last year. All this demonstrates that building a new relationship model has substantial economic, social and public opinion bases, and is each country’s inevitable choice.

Progress has been made in staving off conflict and building mutual trust. A notable achievement is their agreement to report major military operations, and raising a code of conduct on military encounters in the air and at sea.

At the decision-making level, in spite of new problems in bilateral ties, it has been established that maintaining a healthy relationship through dialogue and negotiations is in the interest of both countries. The Chinese leadership’s intentions and expectations of Sino-U.S. ties is best described by the recent remarks of President Xi: “Continually pile up small loads of earth, and a mountain will eventually come into being. Make firm decisive steps, and footsteps will become clearly imprinted on the ground. We should, in this manner, join hands in advancing the construction of a new model of major country relations.”

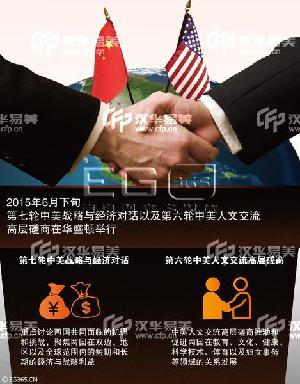

At the Seventh U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue and the Sixth Round of the China-U.S. High-level Consultation on People-to-People Exchanges, both convened in June, the two countries exchanged honest opinions on a range of issues. They included deepening cooperation, building interactive relations in the Asia-Pacific, managing disagreements and sensitive issues, as well as responding to regional hot-button issues and international challenges. Encouraging results were achieved. The two events constitute the prelude to President Xi’s September visit to the U.S.

|

|

U.S. President Barack Obama (fifth right) meets with Chinese Vice Premier Liu Yandong (fourth left), Chinese Vice Premier Wang Yang (third left) and Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi (fifth left) at the conclusion of the Seventh U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue in the Cabinet Room of the White House in Washington, D.C., June 24, 2015. Also seated are Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, Vice President Joe Biden, Secretary of State John Kerry and National Security Advisor Susan Rice. |

- Face History and Maintain Peace– Interview with Japan’s Former Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama

- Building a New Relationship Model for China and the U.S.

- Upgraded Sino-European Relations Take Shape

- China Strives to Strengthen Global Infrastructure Construction and Build a Harmonious World

- Will China Double Your Salary?