The First Chinese to Present Tibet to the West

I still have the October 1912 issue of National Geographic. The cover is worn and torn, but my whole family nevertheless treasures this faded magazine, because it contains the travelogue Lhasa of Tibet that my grandfather wrote, and the 60 photos he took there.

|

|

|

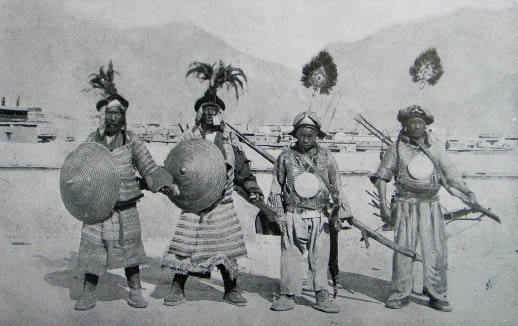

Tibetan soldiers armed with harquebus, bows and arrows – their main weapons. |

Tibet Photography

Our family is descended from the imperial lineage of the Qing Dynasty. My grandfather, Quan Shaoqing, whose family name was Aisin Gioro, was born in Wanping (southwest of present-day downtown Beijing) in 1884. In 1904 he graduated from the Beiyang Medical College in Tianjin, China’s first institution of Western medicine. Taught in English, courses were modeled on those at Western medical schools, and student selection was strict. Graduates mostly became army or navy surgeons. According to my father, as a student my grandfather was passionate about photography, but if he ever took any shots while at university, none has been found.

In 1906, the Qing government appointed Zhang Yintang Resident Minister in Tibet. Among the official convoy that traveled west was my grandfather, who served as a military doctor. During his two years in Tibet, he had time to travel throughout the region, interact with Tibetans from all walks of life, and experience local customs. Armed with his camera, he recorded his experiences there.

The Qing Dynasty was overthrown in 1911. The following year, my grandfather went to the U.S. to study at Johns Hopkins University. The same year the National Geographic published its October issue about China, in which appeared my grandfather’s photos and travelogue. He was the first Chinese to present Tibet to the West through a photo essay.

During the next 20 years, my grandfather was regularly invited to share his knowledge about Tibet in the United States, France and China. His vivid talks were well received, according to reports. “He presented several hundred color slides that enabled the audience to admire palaces in the region and discover local customs, making them feel as if they were actually present at these scenes.”

|

|

|

Yak skin coracles loaded with wool. |

Photolog

My grandfather wrote of his tour of Tibet: “I am glad about the advantageous conditions that allow me to understand Lhasa, as most of my ancestors were not so lucky. First, the indigenous inhabitants are unwary of or hostile towards me. I am also equipped with all the advanced equipment I need to record my journey, and my position gives me the chance to obtain permission to see and shoot scenes that previous explorers could not even dream of. Finally, my tenure was long enough to give me adequate time to thoroughly undertake this creative work.”

Before him, very few Chinese from other parts of the country, let alone foreigners, had been to Tibet. My grandfather wrote in his notes: “In 1904, British troops sent an expedition to Tibet that was eager to unravel the mysteries of this enigmatic city, and which forced opened the gates of Lhasa. However, their curiosity was not rewarded, because they received only hatred and rejection from the local people.” During the 19th century, no more than 10 foreign travelers entered Tibet as scientific explorers or political representatives. But they seldom stayed long due to harsh natural conditions, lack of materials and facilities, and animosity from the local population. Very few managed to reach the holy city – Lhasa.

More than a century ago, Tibetans refused to be photographed. They did not trust photographic equipment, believing that photographing their image would sully their souls. This is why the shots my grandfather took which are of the greatest historical value are the portraits of Tibetan aristocrats, because his position gave him the chance to photolog.

My grandfather said that one day, the abbot of the Sera Monastery came at sunset to pay his respects to Zhang Yintang. My grandfather decided to photograph this lama. Under the pretext of admiring the setting sun he discreetly set his flash, pressed the shutter and snapped the lama. The next day, he offered the shot to him, explaining the principles of photography. The lama was very happy and invited my grandfather to dinner, and asked him to take a family photo. Later, he introduced my grandfather to several high-ranking influential people in Lhasa, including the younger brother of the 13th Dalai Lama, then chief of police and governor of the city.

My grandfather’s pictures cover a variety of topics: politics, religion, traditions, architecture, geography, local people, and wildlife. Among those published in the National Geographic are shots of the Potala, Jokhang and Sera monasteries and the treasures they housed. Other pictures are of unique local vessels – coracles made from yak skin, typical houses with flat roofs and white walls, Tibetan mastiffs, bowls made from human skulls, drums made from human skin, and celestial burial rites.

|

|

Quan Shaoqing (second left) and his family. |

A Century of Vicissitudes

Although taken more than 100 years ago, these photos are still clear. They reflect the Lhasa of that time: poor sanitation, houses that were light in color on the outside, but whose inner walls were blackened by cooking smoke due to having no windows or chimneys, and people and yaks sleeping alongside one another. Rats proliferated in monasteries and infectious diseases were rampant. Many people bore facial scars from smallpox.

My grandfather used to say, “Here, means of transport remain primitive. People do not yet know about coaches. Walking is the most common way of traveling. The local population use yaks and horses when they need to move heavy loads. Only the Dalai Lama and two resident ministers from the central government have the privilege of a palanquin.”

Moreover, he was struck by the contrast between high-born women, who wore precious jewels, silk clothes and furred robes, girls from ordinary families dressed in simple clothes, and poverty-stricken girls in rags. His observations of ethnic clothing styles in the region made my grandfather aware of the strict social hierarchy in Tibet. “Every day, from morning to night, uneducated pilgrims flock to the doors of monasteries which are already crammed with beggars. These poor and ignorant people are in sharp contrast to the lamas who meditate calmly in monasteries loaded with wealth.”

However, the first Westerners to adventure in Tibet described it as a paradise because they acquired only superficial knowledge based on limited impressions, something like the buildings my grandfather photographed in Lhasa: an ostensibly clear and beautiful exterior with a dark, dirty interior.

More than a century has since passed. Tibet has undergone tremendous changes. At the time my grandfather stayed there, it was accessible by only three roads. One was from Qinghai: a relatively flat road, but the trip along it took 18 months. Another was from Sichuan, a faster but more perilous track. The third was from India to the Himalayas and then to Lhasa, which was the route my grandfather took. It took him 103 days to reach Lhasa, and he spent 55 day traversing high mountains in extreme conditions. Today, Lhasa is no longer out of reach. Beijing offers travelers several options: by air in a few hours, by train in two days, or by car in two weeks.

The religion, language and folklore of Tibet are as alive today as they ever were, and most historical monuments and cultural treasures have been well preserved. Visitors to Lhasa can still see worshipers spinning prayer wheels, as in the pictures my grandfather took. They can also still savor Tibetan tea prepared with respect for tradition, and admire Thangka and performances of Tibetan Opera. They can marvel at the Potala Palace, at the Shakyamuni Buddha statue inside the Jokhang Monastery, cliff inscriptions, and the 10,000-Buddha Wall at Mount Yaowang. It is thus possible to take pictures similar to those of my grandfather all those years ago. However, Norbulingka is no longer the attractive but exclusive garden it used to be, but a place of relaxation open to the public. Lamas are not the only group to have mastered writing and medicine. They are still highly revered by the faithful, but more respect is now inspired by religious faith for its own sake rather than as submission to those in power. In addition, the development of the Internet has enabled Lhasa to link up with other Chinese places – even to the world. One can now simply reserve a hotel room or a ticket online to a tourist site in Lhasa, Beijing or the United States.

For many, including my son, Tibet is a region that exerts a powerful attraction. At university his major was photography, and he is now preparing to take a trip to Tibet. He plans to go to the places visited by his great-grandfather and take masses of photos that bear witness to the dramatic changes that have taken place in Lhasa.