By staff reporter ZHANG HONG

By staff reporter ZHANG HONG

LEOPOLD Leeb, an Austrian who has lived in Beijing for 22 years, is a professor at Renmin University of China, where he teaches Latin and other classical languages. He published My City of Inspiration, a new book about his love for the city of Beijing, which he would like to dedicate to his three “lovers” – Latin, ancient Greek and Hebrew.

Beijing: a Stranger’s Hometown

Leeb’s office is spartan. His desk is covered with a cloth, on which are piled his teaching reference books. On the blackboard are written the Chinese characters that mean, “Just do the right thing, don’t worry about the future.” This is his motto, and he tries to live by it.

In China, Latin is studied by only a handful of people. Leeb’s published works, mostly Latin-related, are no bestsellers. But Leeb believes Latin has potential in China and he has never stopped writing about it.

In his new book Leeb records things he has seen and heard in Beijing, as well as his reflections on cultural exchanges between East and West. During our conversation, he refers to the city as “my Beijing” – a very familiar and genial expression.

Leeb’s parents did volunteer work in Africa. His father was a construction worker, and his mother worked in a hospital. Leeb had longed for a life in far-off places since childhood. At the age of 18 he decided to follow in his parents’ footsteps and volunteer in Africa.

Fate, however, brought Leeb to the East. At 21 he went to Taiwan, where he “touched a China using traditional written characters” and became addicted to the language. Three years later he returned to Austria to complete his post-graduate education, and then came to China once again.

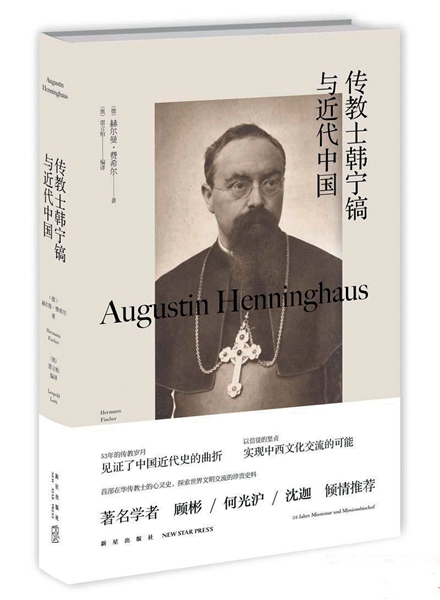

Leeb has published more than 40 works, many are about figures

who have been overlooked, like

the missionary Henninghaus.

Leeb is obsessed with the Chinese language and philosophy. He likes Confucius; he is so familiar with the Analects of Confucius that he often quotes the sayings of this ancient philosopher. His affection for Beijing is “not based on Yanjing Beer or Peking roast duck,” but on something more “spiritual.”

Leeb studied Chinese philosophy under Professor Tang Yijie, a master of the subject, at Peking University. After obtaining his doctorate, it was suggested that he teach German, his mother tongue. Instead, he chose to teach Latin, a more challenging language.

Talking about the two traditions of West and East, Leeb said: “We are never good citizens of the world, as we always prefer one side or the other. None of us can understand the two institutions in a comprehensive and balanced way.”

Leeb’s research focuses on classical languages and their circulation. The Latin language was introduced to China some 700 years ago. It is closely related to English, and they share many common roots. Therefore, it was advantageous for Latin to be better accepted in China than Sanskrit, another ancient language.

Chinese people are becoming increasingly aware of the value of classical languages. They think their understanding of the West and Western culture could be deepened by studying classical languages, and, in return, give some food for thought about Chinese culture. “One will not learn English well,” Leeb commented, “without accruing knowledge of classical languages, as it provides no ability to analyze its origins.”

The Roots of Western Culture

Questions that Leeb tries to answer include: How could ancient Chinese civilization modernize itself, and graft to Western culture? What is the most substantial difference between the two cultural institutions, and what do they have in common?

He knows well the great figures who facilitated communication between the two civilizations, such as the Italian missionary Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) who first translated many classical works of ancient Greece into Chinese. Leeb calls Matteo Ricci the first China expert. “It is from Matteo Ricci that Westerners started to learn Chinese history and philosophy, and vice versa.”

The wave of cultural exchange Ricci initiated continues to this day, and Leeb is one of its inheritors. The three courses that Leeb teaches at Renmin University – Latin, ancient Greek, and Hebrew – each embodies a Western cultural tradition: Latin represents the law and legal culture; ancient Greek is the root of literature, history and science; and Hebrew is the root of traditional beliefs.

Leeb holds that classical languages are the gateway to the intellectual history of the world, because “they are the origin of most ideas in modern times.”

According to Leeb, of all the ideas introduced to China from Europe, the most distinguished is the “rule” – no matter in legislation or grammar. “The rule of law is talked about everywhere in China,” he explained. “In the field of legislation, actually, China doesn’t have much to reference from its own cultural legacy. Legislation was not a discipline in China, but was a specialty of ancient Rome. So it is necessary to learn from the Latin heritage.”

A book on Medieval Europe would most likely not have interested Chinese people 10 years ago, but today things are different. “More people are eager to learn about the overarching structure of modern Western society, as well as the concept of the rule of law and the emergence of the law school in the Middle Ages,” Leeb observed. “Along with a growing sense of history, people long to see the world in a complete and objective manner.”

Talking about the differences and similarities between the West and the East, Leeb noted many values shared by the two cultures, such as a longing for knowledge, love, fairness, and justice. In Leeb’s view, Chinese has become a global language, as it has absorbed many exotic concepts. “China has translated a mass of classical Western works in the last 150 years, so we are actually using the same language,” said Leeb. “What the Chinese read are Chinese characters, but the contents they obtain are universal knowledge.”

Leeb has so far taught more than 2,000 students. Some of them are editors, some teach, and some are studying overseas. The textbooks have become thicker, and the level higher. With more reference books, grammar books and works on related subjects published in China, the substance of Leeb’s classes is now broader. “Recently a book about Latin calligraphy was published,” he said.

The Need for More China Experts

Sun Yu, director of the School of Liberal Arts at the Renmin University of China, wrote the preface to My Capital of Inspiration. He said he sensed the same spirit in Leeb as in wise men from the past. “It is Leeb who introduced us to stories that have been overlooked,” Sun wrote. For example, Fan Shouyi who wrote the first Chinese travelogue to Europe, Zheng Manuo who was the first Chinese scholar in Europe, and the first library of Western languages in China... “He paid special attention to those who wandered around the globe, and expressed deep regrets about the ignorance of the Chinese regarding these stories.”

Leeb believes that “there are not enough China experts, by far.” The Vice President of Renmin University of China, Yang Huilin, at the insistence of his friend, recommended that Leeb take a position at Rome University. Leeb thanked Yang, but declined the offer, saying: “I prefer to stay in Beijing.”

In Beijing, which he calls the “Rome of the East,” Leeb has no social activities, no entertainment, and no family. His book was imprinted with this selfless spirit, Sun Yu commented in the preface, as he abandoned earthly desires, and devoted his life to China, to Beijing. Sun described it a universal love, with a sense of martyrdom.

Leeb has published more than 40 works. All stand quietly in the corner of his office. He wrote about an Austrian abbot, Berchmans Franz Brückner, who came to paint in Beijing and was gradually forgotten. The Austrian ambassador to China wrote the preface to this book.

Leeb also translated Hermann Fischer’s book about Augustin Henninghaus, a missionary who spent 53 years in China. In cooperation with New Star Press, Leeb is currently working on four books; one of them about the Nestorians in China, and one a history of the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) through to the 19th century. He also plans to translate A Dictionary of the History of Christianity in China into English. “We don’t have a good reference book out of China about this period of history,” he says.

Leeb always says he comes from a small country. Compared to China, Austria has an area the size of just one percent of China. “Most Chinese believe the bigger the better.” Leeb is puzzled by Chinese people’s obsession with big things. “Geographically, I don’t think I could ‘digest’ China – any province is 10 times the size of the whole of Austria.”

Students often say to him, “Mr. Leeb, you understand China so well.” “I can’t even understand Beijing,” Leeb quips, “but what I know very clearly is the campus of Renmin University.”

Talking about Beijing, Leeb can’t help getting emotional: “She is an old, charming mother!” He feels the city has become a part of his being.

As a happy “Beijinger,” Leeb is forever grateful to the city for nurturing his spirit. “I love Beijing, and what I have gained from the city is much more than I have given.”