By JOHN ROSS

By JOHN ROSS

FEBRUARY 2017 marks the 45th anniversary of the first Sino-U.S. joint communiqué. Popularly known as the Shanghai Communiqué, it formed the foundation of the relations today between the two countries. The recent U.S. presidential campaign and its aftermath, featuring “China bashing” and even attempts to undermine these long established relations, make essential a clear analysis of why stable, friendly relations between China and the U.S. are in the fundamental interests of both countries and their peoples.

In particular, it must be understood that the 2016 U.S. presidential election culminated in the greatest destabilization of U.S. politics since the Great Depression. Such instability and dissatisfaction are undoubtedly rooted in an economic and social situation where U.S. household incomes are lower now than 15 years ago and a rise in U.S. economic inequality that has been afoot for three or more decades.

Chinese and U.S. officers compare notes during a three-day joint humanitarian relief drill held in Kunming, Yunnan Province in November 2016.

Yet both U.S. presidential candidates attempted during the campaign to divert the U.S. voting public’s attention from these real problems in various ways, one of them “China bashing.” Trump made false claims that China gains an unreasonably competitive edge through an artificially low exchange rate – an argument that even the U.S. Treasury has abandoned.

In fact, “China bashing” goes against the interests of both China and the people of the United States themselves. As the world’s most important bilateral relationship, the dynamics between China and the U.S. affect the global situation as a whole.

Income Trends

U.S. median household incomes in 2015 were still 2.4 percent below the level 16 years previously. And at the trough of the Great Recession, in 2012, they were 9.1 percent below their 1999 peak level. The U.S. population therefore suffered more than a decade and a half of significantly lowered incomes – something which could alone cause deep political discontent and anger in any country.

But the political consequences of the falling U.S. incomes trend were exacerbated by greater social inequality and a lower share by the overwhelming majority of the U.S. population in the nation’s total income. The share of the bottom 80 percent of the U.S. population – the overwhelming majority – in total U.S. income fell from 56 percent in 1967 to 49 percent in 2015. Over the same period, the top 20 percent of the U.S. population’s share in total U.S. income rose from 46 percent to 51 percent. In 2015, therefore, the top 20 percent of the U.S. population received a higher share of the total U.S. income than the bottom 80 percent.

This inequality has become more pronounced since Reagan’s presidency in 1981. From 1980 to 2015, the bottom 20 percent of U.S. households’ share in the total U.S. income fell from a low of 4.2 percent to 3.1 percent. Simultaneously, the share of the top 5 percent of U.S. households in total U.S. income underwent a sharp 5.6 percent rise from 16.5 percent to 22.1 percent. Meanwhile, the share of each household income group in the bottom 80 percent of the U.S. population in total U.S. income showed a sharp 7.1 percent decline from 55.9 percent to 48.8 percent.

Given these dramatic and growing income disparities since 1980, the rising political instability in the U.S. is no surprise.

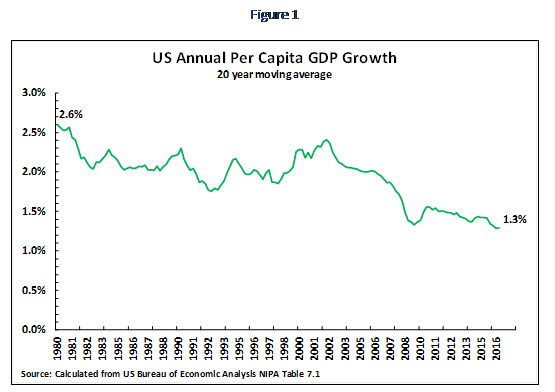

The fundamental economic reasons behind these negative trends in U.S. incomes are equally clear. Figure 1 shows that, when taking a 20-year moving average to remove all effects of short-term business cycle fluctuations, between 1980 and 2016 the annual growth of U.S. per capita GDP fell by half – from 2.6 percent to 1.3 percent. That this slow economic growth was accompanied by a radical increase in social inequality explains the fall in U.S. median household incomes.

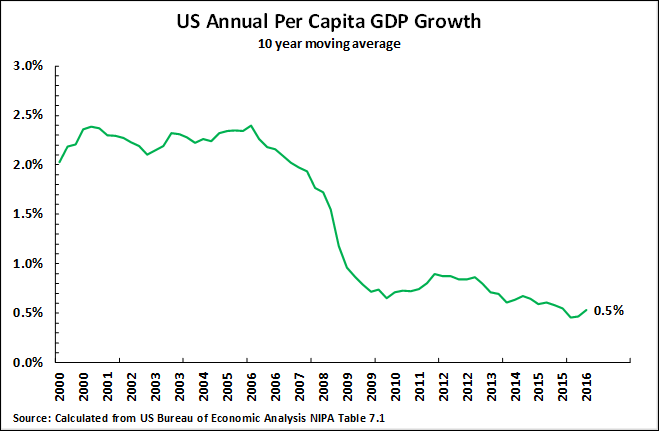

Recently, this slowdown in the U.S. economy has worsened. As Figure 2 shows, under the impact of the international financial crisis the 10-year moving average of annual per capita GDP growth in the U.S. had fallen to 0.5 percent – close to stagnation – by the second quarter of 2016. Such miniscule per capita economic growth made impossible any significant increases in the living standards of the American people.

A Win-win U.S.-China Economic Relationship

While, as analyzed below, foreign trade and investment are not main factors in the recent U.S. economic performance, the correlation of trade expansion and positive economic performance is nevertheless widely acknowledged – both theoretically and factually. Adam Smith said in the first sentence of the first chapter of his seminal work on modern economics The Wealth of Nations: “The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labor, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is directed, or applied, seem to have been the effect of the division of labor.” The division of labor necessarily applies both internationally and domestically. Numerous factual studies have confirmed the positive correlation between economic openness and faster growth.

This economic conclusion is also confirmed, in the negative sense, by the world’s post-1929 relapse into the protectionism that presaged the Great Depression – the greatest economic crisis in modern world history. It was indeed this catastrophic experience that moved the U.S. after World War II to reverse its previous protectionist course and, for half a century, promote an open world trading order – one with great “win-win” benefits for both itself and other countries. Globalization brought great benefits to economies – not only to the U.S. but also to China in the wake of its reform and opening-up policy of 1978.

A tourism campaign is launched in eastern China’s Suzhou City in October 2016 as part of the China-U.S. Tourism Year.

At the present stage of globalization the economic relations between China and the U.S. are critical. The U.S. and China are the world’s first and second largest economies, accounting for 39 percent of the world economy at current exchange rates. They are hence the world’s first and second largest trading nations.

In summary, China and the U.S. combined are sufficiently powerful to play a decisive role in the world economy and in world trade. Approaching the question of how to achieve optimum development of world trade and investment, therefore, necessitates discussions between the U.S. and China.

Furthermore, it is easy, from the point of view of economic fundamentals, to understand and build on the framework of mutually beneficial economic trading relations between China and the U.S. due to the two economies’ different features.

China is the world’s largest “upper middle income” economy, while the U.S. is the world’s largest “high income” economy. Consequently, as regards medium technology items, China enjoys the combination of a comparable technological level but with much lower labor costs which the U.S. cannot match. Therefore, China has a decisive competitive advantage in medium and medium-high technology products. If, rather than importing these medium technology products from China, the U.S. were to manufacture them, the result would be substantially higher prices for U.S. consumers and producers, and consequently lower U.S. living standards and U.S. international competitiveness.

But, equally, the U.S. has competitive advantages over China as regards high technology. China’s per capita GDP, which reflects the contrasting productivity of the two economies, is only 27 percent of that of the U.S. measured in PPPs – the most appropriate unit for long-term comparisons. Even with the best economic policies, therefore, it would take China several decades to equal the U.S.’s level of productivity. In other words, the U.S. will continue to enjoy a comparative advantage over China as regards high technology products for several decades to come.

The “win-win” outcome of economic relations between China and the U.S., therefore, is clarity and stability in both the short and long term. China will continue to be able to produce medium and medium-high technology goods more competitively than the U.S., which will meanwhile enjoy a competitive advantage in the field of high technology products.

The two economies’ fundamental complementarity accounts for the dynamism of trade between China and the U.S. That the U.S. is China’s single largest export market is well known. But since 1999, China’s share of total U.S. exports has increased 5.3 percent, whereas that of the EU declined by 2.8 percent and Japan’s by 4.6 percent. In short, the growth of U.S. exports to China is much more dynamic than it is to either the EU or Japan. Simultaneously, China’s share of total U.S. imports rose by 11.2 percent, while that of the EU fell 0.2 percent, and Japan’s by six percent.

Finally, from a geopolitical standpoint, there is no call for any military confrontation between the U.S. and China. No significant force on either side envisages a nuclear war between the U.S. and China, because that would result in the devastation of both countries. As the U.S. is protected on one side by the Pacific Ocean and on the other by the Atlantic, a conventional military invasion of the U.S. is also inconceivable.

Having analyzed the mutual benefits of “win-win” relations for China and the U.S., I next examine the consequences for the U.S. population of any U.S. decision to confront China, that is, to progress from verbal to physical “China bashing.”

Consequences of Confrontation with China

Both the U.S. military build-up under Reagan and George W. Bush were limited in scope. Reagan’s aim was not to fight a war with the U.S.S.R. but to exert economic pressure on the Soviet Union at a time when the Soviet economy was growing less rapidly than that of the U.S. Meanwhile the military forces of George W. Bush’s targets, Afghanistan and Iraq, were pitifully weak when compared to China’s. But even Reagan and Bush’s partial military build-ups nevertheless destabilized the U.S. economy and swelled the national debt.

A U.S. confrontation with China, whose economy is growing much faster than that of the U.S. and which possesses military forces considerably more powerful than those of the Taliban or Saddam Hussein, would require a further massive diversion of U.S. resources into military expenditure, and consequently far greater destabilization of the U.S. economy than was ever witnessed under Reagan or George W. Bush. This, in turn, would affect the political dynamics within the United States.

If the U.S. were to be directly attacked, its people would of course make immense sacrifices and display the same bravery as those of any other country. The U.S.’s loss of life during the Pacific War after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor was small compared to China’s, but the bravery of individual U.S. soldiers fighting in Iwo Jima and Okinawa was equal to that displayed by Chinese soldiers battling Japan’s invasion.

Between 1940 and 1945, the percentage of U.S. household consumption as GDP also fell from 69 percent to 53 percent, due to the huge diversion of resources into military expenditure. But it brought no serious social discontent or destabilization in the U.S., whose people logically and rightly considered these sacrifices necessary and justified to repel any direct attack by Japan on the United States.

But the U.S. population has since WWII, again logically and rightly displayed a growing antipathy to making sacrifices for non-core U.S. interests or conflicts. This has intensified with the slowdown of the U.S. economy and relative decline of U.S. economic dominance. U.S. public opinion has therefore shown a clear trajectory of growing popular opposition to the launch abroad of any major military actions unless U.S. core interests are directly threatened.

A U.S. decision to confront China, not necessarily in a war but in an attempt to exert on it serious pressure, would of course require far greater sacrifices from the U.S. population than earlier conflicts. But local wars (Vietnam, Iraq) and military build-ups against economies growing less rapidly than the U.S. both destabilized the U.S. economy and caused a decline in the people’s living standards.

U.S. public opinion, as evident in polls, may or may not be favorable to China. That is something that changes periodically. But the facts as explained above show a clear absence of any indication that the U.S. population would willingly make the economic sacrifices necessary to confront China.

On the contrary, all evidence shows that, unless China were to make a serious and provocative foreign policy miscalculation that recklessly and aggressively threatened U.S. core interests, or major policy errors that slowed down China’s economy, the U.S. population would shun the concomitant ramifications of confronting China.

Conclusion

These economic processes clear two fundamental paths for the U.S. people. The first, which correlates both to the interests of China and the prosperity of the U.S. people, is that whereby the U.S. seeks “win-win” collaboration with China. This means that, for example, important trade negotiations between the world’s two biggest trading nations – China and the U.S. – would be oriented towards cooperative agreement, rather than, as in the TPP, protectionism. U.S. foreign policy would thus seek to lighten the burden of military spending by lessening direct tensions with China and seeking agreements with the country, and other powers, in efforts to avoid and contain regional conflicts. This is indeed in the interests of China but also takes into account the prosperity of the U.S. people.

The other path – of U.S. confrontation with China – would mean a further plummet in the U.S. population’s living standards. It would also have an even more economically destabilizing effect on the U.S. than its confrontations with the U.S.S.R. while in economic decline or the militarily weak Afghanistan and Iraq.

In short, “China bashing” is in the interests neither of China nor of the U.S. people.

JOHN ROSS is a senior research fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University.