By staff reporter ZHANG HUI

By staff reporter ZHANG HUI

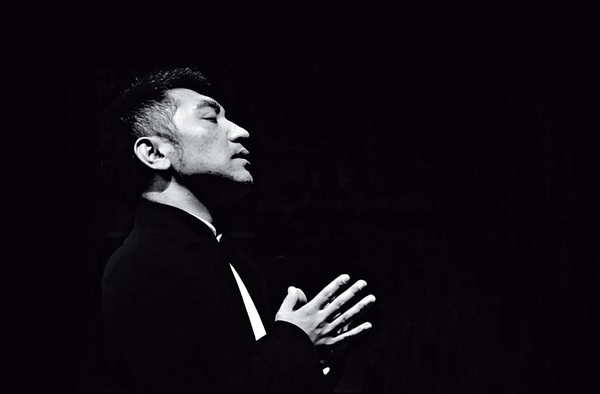

WESTERNERS in the 59th Grammy Awards audience wowed songstress Adele’s five-trophy sweep and basked in Beyonce’s epic performance of a five-song medley. Chinese music lovers, meanwhile, delighted in Wu Tong of the Silk Road Ensemble’s Best World Music award for the album Sing Me Home. It was Wu’s second Grammy.

“I’m happy, though not astonished, to get the award, because it means that more people will appreciate the distinct beauty and cultural inclusiveness of our music,” Wu Tong told China Today. He added, “Over the past 18 years since it formed, the ensemble has set out to bridge different cultures with music, in hopes that it will help people of different nationalities and belief systems to respect and better understand one another. This, to me, is the true meaning of Best World Music.”

When recalling the Grammy awarded to Yo-Yo Ma for his collaborative album in 2010 – the first ever shared by Chinese artists – Wu said, “That was a surprise. I did not expect Yo-Yo to include Happiness, a distinctly Chinese song based on the Chinese pentatonic scale, on Yo-Yo Ma & Friends: Songs of Joy and Peace. It won the Classical Crossover album award.”

Eliminating Dissension

The past few years have seen a warm response from the international community to the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative. The project tallies with the hopes of many countries for cooperation, exchanges, and development. As early as 1998, aware of the importance of musical exchanges and fusion, Yo-Yo Ma, inspired by the ancient cultures and traditions of countries along the ancient Silk Road, decided to start a band made up of composers and performers from all over the world. His aim, as stated on the band’s website, was to “explore how the arts can advance global understanding.”

Wu Tong summarized the ensemble’s mission: “to eliminate dissension with music.” As a founding member of the ensemble, Wu Tong was invited to join in 1999 after giving a lecture at the University of Michigan, and made a performance tour of the United States. Wu complemented his performance with an explanation of the history of the 16 traditional Chinese wind instruments that he played during the show.

Wu enacts the multiple roles in the ensemble of composer, vocalist, and player of several traditional Chinese music instruments.

“What we create is a kind of crossover music that blends diverse styles, from the traditional folk music of various countries to classical, modern and popular music. As well as playing instruments, we also sing, dance and play rap. We’ve never confined ourselves to any set style. Our ensemble has nurtured an open and free space where each musician freely expresses themselves. I instill Chinese elements into our music, including rock, traditional folk music, and even local opera,” Wu said.

The ensemble’s achievements, as might be expected, owe a lot to its founder and art director, Yo-Yo Ma. Ma has invited world-renowned musicians of various nationalities to create and adapt music for the ensemble. Wu revealed that Yo-Yo Ma donated the personal prize of US $500,000 he once received as an award to the Silk Road Fund. No one in the ensemble knew until a few years later.

“He is the most polite and considerate of all ensemble members. He is modest and kind to everybody. Once on stage, he presents with his cello diverse human facets, often with a passion that arouses people’s inner zest for life, but sometimes creating an exquisite, delicate, heartrendingly tender ambience,” Wu said. “He is also extremely diligent, and constantly hones his skills. I’ve never known him to be daunted by any musical challenge.”

Yo-Yo Ma also does his utmost to create a free atmosphere in the ensemble where musicians can express their ideas. “He is a music maestro. He might be dogmatic, and nobody has a problem with that. But he always listens. During a meeting, he tends to keep quiet and give others a chance to say what’s on their minds. This makes us feel valued and integral to the team. Both his devotion to music and composure when under pressure are admirable. Yo-Yo is a friend and mentor to me,” Wu said.

When explaining the ensemble’s approach to music creation, Wu said, “One composer is generally responsible for one piece of work, but sometimes two might work together. Sometimes a few work together on improvising a melody. There are diverse ways of creating works. If you are improvising, other members help by tuning in to your theme, or even creating crescendos that set off your performance.”

A video titled, in Chinese, “Yo-Yo Ma intoxicated by the face-off performance of Chinese Sheng (a wind instrument) player Wu Tong and their Indian drummer” went viral online. Wu commented, “That was a perfect example of musical improvisation, and also trust.”

The performance took place at a concert in Boston to commemorate the 15th anniversary of the founding of the ensemble. “When our show ended, the audience still wanted more, and demanded encores. But at that moment I didn’t want to perform a traditional Sheng piece because I felt the urge to give the audience something new. So I improvised that melody on the Sheng. Inspired, our Indian drummer Sandeep Das joined in with an impromptu performance,” Wu explained. It’s rare in a performance of classical music for a player to join in unbidden, because they generally follow the music notation. “However, for us, musical ad libbing is welcome. We improvise a piece on stage, so teasing and taking the audience by surprise, and keeping each other on the hop.”

The more people became familiar with the Silk Road Ensemble, the more fascinated they became with the unfamiliar, and sometimes unimaginable sounds it created. “Chinese and Indian folk music blends well. Traditional Iranian music also complements European classical music. We make these apparently impossible musical mixtures possible,” Wu said.

As the ensemble constantly produces new albums and makes regular world tours, it wins more and more fans. Apart from being drawn to its unique music, people also sense the chance to communicate with different cultures on a level beyond their music. The Vancouver Sun described it as “one of the 21st century’s great ensembles” and the Boston Globe as a “roving musical laboratory without walls.”

The Grammy-winning album Sing Me Home features works by composers other than ensemble members, from many different countries and regions, including India, Central Asia, and Africa. “Different nations have different interpretations of home. The song Going Home that I sing from the album recreates a nostalgic melody from a symphonic piece by Dvorak. It interprets home as a haven for one’s soul. Diversified interpretations of home make it possible for everyone to find common points of familiarity,” Wu said.

Ma, recipient of 18 Grammys, wrote on his website: “Since the very beginning, the Silk Road Ensemble has been about departure and explorations, new encounters and homecomings. The music composed, arranged, and performed by ensemble members and our friends on Sing Me Home is a tribute to how culture helps us all to meet, connect, and create something new.”

“Apart from being an expression of approval for our efforts over the past 18 years, I think the Grammy might also have implied the award panel’s mindset amid the intensified globalization which is still punctuated by backlashes and instances of cultural estrangement among certain nations,” Wu said.

Crossover Musician

Most Chinese people heard of Wu Tong in his capacity as vocalist in the Lunhui (samsara) rock band. The group rocked the country with its famous song The Flames of Yangzhou Road in the early 1990s, when Wu was still a student specializing in Chinese folk wind instruments at the Central Conservatory of Music.

Wu was the first Chinese musician to fuse rock and Chinese folk music by playing his Sheng to rock music. He adapted The Flames of Yangzhou Road from a famous poem of 1205. “I intended to bring out through rock the essential masculinity and heroism of ancient generals as expressed in the Song Dynasty poem. There is actually an affinity between the poem and rock music, because rock evokes the full power, grandeur and belligerence of combat. My later works, like Man Jiang Hong (The River All Red), have a similarly martial flavor,” Wu said.

Although Wu earned his fame as a rock musician, he has also sung folk songs on the grand CCTV annual Spring Festival Gala stage.

“I don’t like being confined to a specific style,” Wu explained. He once observed, “People encounter countless appealing scenery in their lives. There are many pretty and splendid flowers, and each one is gorgeous. We don’t have to appreciate just one and ignore the rest. What I like is naturalness.” He feels the same about styles of music.

After he joined the Silk Road Ensemble, rapt as he was in Sheng playing, many doubted Wu Tong could ever forsake rock music. Then, in January 2016, came the release of a new version of The Flames of Yangzhou Road.

“I’ve never said I’d leave rock music, and never regarded any style of music as unsuitable for me. I think elements of folk music can be incorporated into rock, and vice versa. Rock doesn’t necessarily denote cynicism or rebellion. I think it can be positive and bright, even gentle. Rock has brought me freedom and individuality as well as power. It is important to give it proper employment and expression, once I master this language. I could use any style in my music because all are the fruits of human wisdom. Blending them and creating melodious music is both my job and interest,” Wu said.

Bringing Chinese Music to the World

Wu’s career is closely associated with the traditional Chinese Sheng wind instrument. Wu was born into an old and illustrious family of Chinese folk musicians. He started learning the Sheng from his father when he was five.

“First I played a cute little Sheng, a gift from my grandfather. Half a year later, my father replaced it with a bigger one he had made from rosewood. It’s very heavy, with 21 pipes and metal tubes. Holding it for at least four hours a day is actually torture for a six-year-old.”

Wu began to become fond of the Sheng when he was around 12. “Then, having got through the difficult beginner’s stage, I mastered all the basic Sheng skills, and was able to perform some pleasing tunes and songs. I even won first prize in a national competition.”

Later Wu enrolled in the middle school attached to the Central Conservatory of Music, and later the conservatory itself, majoring in traditional Chinese folk music. “I had been one of the top three in my class. There was no longer any mystery about Sheng playing techniques for me, and I became aware of a growing feeling of dissatisfaction. Actually in those days, I had not apprehended the true beauty of the Sheng because I lacked the necessary accumulation of life knowledge.”

The history of the Sheng can be traced back to the pre-Qin period (c. 2100 – 221 BC), as an important instrument for courtly music.

“The Sheng is rooted in traditional Chinese culture. Its physical structure is actually an imitation of growing, living things. The Sheng correlates with springtime, when everything grows. So its music evokes a pleasantly uplifting feeling. It’s extremely melodious and elegant when heard at the Spring Festival. It never makes people feel sad. Yet the joy it conveys is moderate and refined, never over the top. It thus accords with the Confucian concept of the ‘golden mean,’” Wu said.

Wu spoke of how he dabbled in rock at college in efforts to find a new way of musical expression. He so summarized his musical life: continuous addition until the age of 40, subtraction thereafter. Before he reached 40, Wu was obsessed with learning different forms of musical expression, including instruments. Then one day he came across The Ode to the Sheng, by Pan Yue (247-300) of the Jin Dynasty (266-420), which spoke of the Sheng aesthetic.

“It applauds the Sheng as a wonderful instrument, because the sound it produces is straightforward but not stiff, and can be melodious and mellifluous, but not too ornate. The ode emphasizes the beauty of the Sheng as existing in its simplicity. Suddenly I knew what I had failed to apprehend about Sheng and why I was dissatisfied. This led the way for my better tapping and appreciating the beauty of this instrument,” Wu said.

For the next two years or so, Wu turned down all invitations to perform and devoted himself to reading and delving into ancient books that made reference to the Sheng. He strove to delineate the evolution of the Sheng and its spiritual essence.

“The sound the Sheng makes is harmonious but simple. Its spiritual essence lies in the harmony between human beings and nature. However, differences in musical scores make it hard to adapt ancient music to modern sounds. Even though people are trying to re-create ancient classical music works like High Mountains and Flowing Waters, these are no more than modern replications according to conjecture. So when I perform classical works on the Sheng, I simply focus on its spirit, and try to generate a sound that reflects the harmony between humankind and nature. But to do that I need first to find my inner peace, and only then can I convey the harmonious sound that might bring people a measure of solace,” Wu said.

So, since turning 40, Wu has attempted to simplify his form of musical expression. “However it’s not easy to attain the power of simplicity, or stick to the simple. First of all, you need to be confident about your culture, and aware that simplicity can help you find peace of mind. This requires attainment of a certain degree of self-cultivation,” Wu explained.

Over the past few years, Wu has been thinking about how to promote traditional Chinese music through the Silk Road Ensemble. “I think what’s most important is that we should dare to be ourselves. Imitation will not make you surpass others. When you are able to present your particular unique beauty, others will then start to appreciate you. Our culture imbues so much wisdom and fine arts which we need to discover. If they could be employed in our music and lyrics, it would help shape our unique beauty and refinement. Garnering global awards will then be just a matter of course,” Wu concluded.