A Language Created by Women, for Women

MANY centuries ago, the womenfolk in Hunan Province’s Jiangyong County and its adjacent areas created an esoteric written script for their exclusive use.

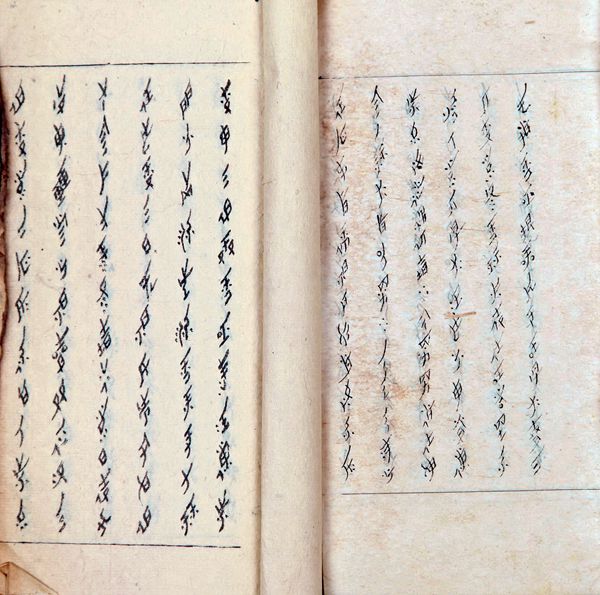

Its rhomboid shape and thin strokes gave rise to the epithet long-legged, or ant characters. As it was the sole reserve of the women of Jiangyong and neighboring counties, however, and completely indecipherable to men, scholars have named it Nü Shu, or Women’s Script.

These rhomboid-shaped characters are used solely by the women of Jiangyong County and its surrounding areas.

The absence of records or original examples of this writing makes it difficult to pinpoint when it began to evolve, but what is certain is that it is the only known gender-specific language in the world.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, in 2006, Women’s Script was included in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritage.

Women’s Spiritual World

Nü Shu, used in villages along the Xiaoshui River in Shangjiangxu Town of Jiangyong County, not only refers to the characters themselves as well as works written in these characters, but includes the chanting and singing of these works. Even in this small enclave where the language evolved and was prevalent, not all the women there have mastered it, at most around one or two out of every 10.

Nü Shu literary works were usually in seven-character verses which expressed the bitterness of the lives of the women who wrote them. Women sourced writing implements from everyday things, using twigs as pens, soot for ink, and writing on cloth, coarse paper, paper fans, or silk handkerchiefs.

Women read and chant their own works while doing needlework.

The works have various themes. Those most creative are the Three-Day Books and Articles by Sworn Sisters, the latter of which are testaments to eternal friendship among women. Some works set down the lyrics of folk songs, ballads, and dirges chanted at funerals and sacrificial ceremonies. Others are adaptions of popular works of literature. For these women, reading and chanting their works was a pastime to be enjoyed when they gathered to do needlework.

The women wrote mostly about their daily lives rather than making social commentary. Unlike other folk songs, few of their compositions related to creation myths. They were rather preoccupied with the more personal matters of marriage and family life, love affairs, anecdotes, folk songs, and riddles.

Given the dictates of the prevailing patriarchal society, women generally did not go to school. They were expected to stay at home and keep the household running smoothly. The sewing bees where the women of Jiangyong gathered to sing and teach one another Nü Shu were precious opportunities to meet and exchange inner thoughts. Public activities like funerals, sacrificial events, and theatrical performances were main sources of their creative inspiration.

Women’s Script was passed down for generations from mothers to daughters. This extraordinary writing system allowed otherwise uneducated and illiterate rural women to record their thoughts and write stories. Moreover, the creativity they inspired in one another formed life-long bonds among these women. Their works were created with the intention of being shared and sung with fellow sisters rather than as private diaries.

Lyrics

Women’s Script was openly sung and chanted, so the younger generation of women could learn it and pass it on orally.

Researchers have discerned fixed tunes in the sung Women’s Script. They are in the three basic scales of high, middle, and low pitch. The repetition of simple tunes and scales imbues the songs with an innocent, pristine quality. As Nü Shu phonetically records the local Jiangyong dialect, the tunes naturally convey its seven tones in specific rhymes.

Women’s Script was included in the first batch of national intangible cultural heritage in 2006.

The function and value of Women’s Script come to the fore at weddings, fairs, and other folk activities. It is traditional in Jiangyong to hold a night-long song fair for a bride shortly before her wedding day. The venue for the event, usually the Hall of the Clan, is hung with red lanterns three days before the wedding, and the tables heaped with candy and local delicacies. Bridesmaids and the bride’s female relatives and friends are invited to sing and so bid her farewell. Women sing and read stories in Women’s Script till dawn, enjoying the last hours with their friend until she joins her prospective husband’s family. These pre-wedding celebrations are, in effect, “hen nights”, although there is no fixed date on which they are held.

Professor Gong Zhebing of Wuhan University, one of the academics to discover this esoteric language, regards the local dialect as the social soil that nurtured Nü Shu. The construction of rural schools after the 1911 Revolution and the drive to eradicate illiteracy after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 gave local women access to school education. There they learned to read and write the official language, Putonghua. The subsequent decline of Women’s Script was one of the many cultural sacrifices to social modernization.

Mystery to Explore

Professor Gong Zhebing came upon this female script in 1982 while on a field trip in Jiangyong. He and other scholars first regarded it as a code rather than a written language. As research into the script expanded, Gong and linguist Yan Xuejiong, then vice president of the South-Central University for Nationalities, co-wrote in 1983 a paper analyzing Women’s Script. When made public at the 16th International Sino-Tibetan Linguistics Conference in the U.S. it aroused great interest in international academic circles. Meticulous research by scholars from the U.S., Japan, and Australia as well as domestic institutions such as Tsinghua University and South-Central University for Nationalities, ensued in Jiangyong’s villages.

Among the legends surrounding the origins of the language, that most prevalent tells of women creating the script according to the patterns they embroidered on the cloth they had weaved when they gathered to do needlework. Excluded from school, and thus unable to study official language, women dared to create their own. This story confirms, from another angle, that Women’s Script was related to standard Chinese characters.

Other scholars support this theory. They found that Women’s Script records a type of Chinese dialect through adapting standard Chinese characters. As this transformation varies in an arbitrary fashion, however, it is hard to relate the form of Women’s Script to standard Chinese characters. But researchers have agreed on three levels of variation – strokes, structure, and form. Owing to the randomness of the script, many characters have variant forms. This makes it difficult for researchers to agree on their exact number. Estimates range from around 100 to 3,000, depending on the different materials and sorting criteria.

As a member of the Chinese linguistic family, Women’s Script is distinctive for its graphic phonetic feature, whereby one character represents a group of homophones. Standard Chinese, in contrast, is a typical ideographic language. As Women’s Script was commonly embroidered on clothes or cloth belts, its characters appeared smaller and more curved. This singular mode of writing endows special status on Women’s Script in the history of the development of language.

Women’s Script constitutes a cultural fossil whose significance embraces anthropology, ethnology, sociology, linguistics, philology, ethnology, and archaeology. It is of inestimable value to researchers of the origins of human languages and civilizations, and of women’s cultures. Unfortunately extant literary works in the script are more or less non-existent. They would, in accordance with convention, have been burned when their writers passed away or buried as sacrificial objects. It was seldom that any works remained as legacies to daughters or female friends in commemoration of the deaths of women who had compiled works in Nü Shu.

There are few historical records or local chronicles that refer to Women’s Script, or mention of it in clan family trees. No such works have been found among local excavated relics. The sole reference to Nü Shu is that of a few lines in the Survey Notes on Counties of Hunan Province by Zeng Jiwu in 1931: “Each May, women from various towns gather to burn incense, pay tribute, and sing together while holding fans on which songs have been written. The characters on these fans are as small as a fly’s head, similar to Mongolian characters. I met no men in the county who could read this script.” With no other materials to go on, the academic field is far from a consensus on the creation and development of this language.

The last natural successor of Women’s Script, Yang Huanyi, passed away on September 20, 2004. As those privy to the key to this exotic written medium are no more, many characters may forever retain their inscrutability.

(Compiled by China Today)

Services

Economy

- Foreign Companies Opting Out?

- China Set to Hit Target of Eliminating Poverty – An Interview with Bert Hofman, the World Bank’s Country Director for China, Mongolia and Korea

- Trade Protectionism Should Not Be Advocated

- CPC’s “Thought Leadership” Increasingly Important Around the World

- China-Canada Joint Efforts to Address Climate Change