Online Literature Spearheads China’s Cultural Industry

By staff reporter VERENA MENZEL

MEDIA, no matter print or broadcasting, television or the Internet, are more by far than just simple carriers of content, or transmitters of information. Each, through their medial preconditions, shapes during the creative process the content that they transmit.

The first online microficiton blockbuster.

This is especially true of the Internet – this dominant communications medium of the 21st century. China presents a compelling example of changes in classical content patterns that are attributable to the rise of the World Wide Web.

New Market Segment

The Internet has in recent years turned the classical literature industry as we know it in the West on its head. Since the turn of the millennium, a new form of literary writing has been hugely successful throughout China – that of online or web literature.

The popularity of smart phones spurs online reading and interaction between writers and readers.

The scope of web literature, however, is far broader than that created in the traditional manner and republished digitally on the net. Online literature also encompasses works composed specifically for this new medium. They are not only first published on the web, but also molded by the particular features of their target medium, for example, its immediacy and fast pace, low entrance threshold, detachment from the limitations of hard materials such as paper, and most especially its strong interactivity.

The result is an array of brand new concepts of literary writing, from digital poetry, literary weblogs and “micro fiction” to so-called collaborative writing. Most of these new genres are strongly influenced by the direct interaction between author and reader that the Internet provides – one utterly unforeseen in the realm of traditional books.

Results of a study by Chinese online portal sootoo.com in the first quarter of 2015 showed that around 350 million people in China regularly read online literature. Three years earlier, in 2012, the figure was around 233 million.

In the same study, 85 percent of respondents stated that they preferred and so generally read digital rather than printed publications. Furthermore, the average time spent on reading books or long articles on mobile devices by those citing reading as their favorite pastime amounted to 84.6 minutes a day. Reading, therefore, easily topped other mobile pastimes such as listening to music (an average 72.6 minutes per day), browsing social media (66.1 minutes), playing online games (54.6 minutes) or watching online videos (45.8 minutes).

Between 2012 and 2015, the market volume of the new web literature sector expanded from RMB 2.7 billion (€ 364 billion) to RMB 7 billion (€ 943 billion). Online literature has hence become a promising sector of China’s cultural industry.

Against that backdrop, it is no surprise that Chinese Internet giants like Alibaba and Tencent have in recent years invested generously in this nascent but growing market segment. Such outlays include the contracting of web authors whose works are published on their reading web portals.

Tencent, for example, which amongst other things runs China’s most successful messenger service QQ and the popular social media app WeChat, embarked in early 2015 on large-scale cooperation with Cloudary, the online publishing house belonging to the Chinese Shanda Group.

Since its establishment in 2008, Cloudary has established five hugely successful online literature websites that provide more than six million online publications, and signed contracts with more than 1.6 million authors. Within just a few years, Cloudary has become the country’s biggest provider of web literature. Tencent’s cooperation with the Shanda Group underlines the great importance that China’s big IT companies place on the rising online literature industry.

Why China?

But what makes web literature so successful in China, while in many Western countries it tends to be a niche sector? Why is this new form of literature so appealing to both readers and entrepreneurs?

Answering these questions calls for a closer look at the development of China’s literary industry since the onset of reform and opening-up. In the past, literary journals traditionally constituted the main driving force of China’s literary world as well as the most important literary mainstream medium. Readers loved these journals, and they often acted as stepping stones for promising new writers.

However, after implementation in the late 1970s of the reform and opening-up policy and the growing market-orientation and niche formation it engendered, China’s literary journals gradually lost their function as a mainstream medium.

The Internet started to fill this gap at the end of the 1990s. Owing to its low entrance threshold and thanks to the fresh possibilities for expression it offered, the web became a new creative playground for young and as yet unknown authors, as well as for an army of amateur writers.

Han Han, one of the first popular web authors.

In 1997, the first Chinese online literature web portal Rongshuxia.com, which literally means “Under the banyan tree,” appeared. Users of this new website both submitted their own literary works and read those of others, for free. In just a few years, many young writing talents thus matured “under the banyan tree,” among them such famous names as Han Han, Ning Caishen, Jin Hezai, and Murong Xuecun.

Since then, the online literature market has experienced a golden age of development. The first years of self-discovery and willingness to experiment, however, were gradually superseded by growing commercialization and the establishment of online publishing houses.

However, this development has not spoiled readers’ enthusiasm for the new genre. Statistics from China’s biggest Internet industry website sootoo.com show that online novels score the highest points among young, urban readers living in big cities like Beijing or Shanghai, 85 percent of whom have yet to celebrate their 40th birthdays. Most new web authors are also part of the emerging Chinese middle class born in the 1970s or later.

Writer-reader Interaction

What makes new online works so special is their optimum use of new media interactivity. It is arguably this feature that makes these books so appealing. Readers and writers can enter into a more or less direct dialogue on the Internet via both comments that the audience posts directly below such publications and during the actual creative process as well.

Inspired by the new possibilities this medium offers, genuinely new literary genres have appeared, such as collaborative writing, where several authors write a single novel or story, or it is completed through the participation of netizens themselves.

Another example of these literary forms is that of so-called micro fiction. In opposition to the sheer infinity of virtual space, authors of this genre impose on themselves strict limitations as regards length. Similar to tweets on the social network Twitter, the literary content of these literary micro-bites is condensed to a maximum 140 Chinese characters, equivalent to a few short sentences.

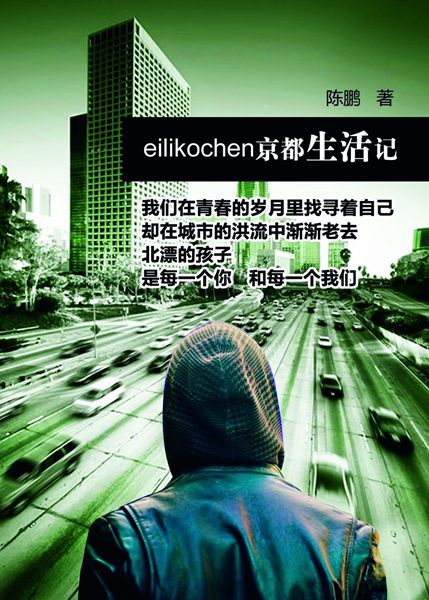

One author who has won micro fiction fame is Chen Peng. In 2010 he published his micro-series “Life of eilikochen,” a lyrical collage of written daily life snapshots. It was a huge hit in China’s online society.

However, the most common Chinese web literature remains that in the traditional narrative forms of novels or short stories. They feature such genres as crime fiction, fantasy, and science fiction. But ancient narratives set in the imperial court and offices, student stories, time travelling tales, as well as tomb raider adventures, also enjoy great popularity among the young Chinese readership.

Their narrative content is often published chapter by chapter, or as a series, so formally reflecting the specific features of the digital reading process characterized by a comparatively short attention span.

Mature Production Chain

Perhaps most important, this formal adjustment to the target medium at the same time creates an ideal link for commercial remarketing of literary content through other media channels. It is this potential for remarketing that could account for the great success of Chinese online literature. It might also explain why this particular segment of the cultural industry segment does so well in China.

Whichever author achieves a breakthrough on the Internet in China stands a good chance of finding their way into the traditional print market. A typical success story starts with Internet-hype, transforms into a re-publishing of the story in book form, and ends in adaptation of the content into a script for a movie or TV series, or as a basis for manga, comics, or computer games.

Thus, over the past years, a mature production chain has been spun into China’s web literature, and the cycle from online breakthrough to remarketing in other media has become shorter.

Here China differs somewhat from industrialized nations like Europe and the United States, as well as its Asian neighbors Japan and South Korea, where specific pop culture production mechanisms for all types of media were fully developed well in advance of the Internet era.

In these countries, genre novels have for many years been successfully remarketed as movie or television adaptations, and remodeled into cartoon or manga books. But in China these economical mechanisms did not emerge until much later.

Whereas most marketing structures remained stable in the Western industrialized nations after the Internet arrived on the scene, albeit with certain small adaptations, in China these mechanisms were relatively underdeveloped upon the advent of the World Wide Web. They therefore seemed more amenable to adaptation.

China’s first web literature portal.

In China, the success of the Internet suddenly opened up a whole new space, which young amateur and professional writers put to maximum use. As a consequence, new emerging Chinese writing portals could absorb many resources formerly controlled by the traditional literary industry. In the fully developed literature markets of many Western countries, however, these resources stayed in the hands of big, long-established publishing houses.

Over the last years, new cultural players in the literature market have managed not only to build a huge fan base but also to attract cash from the anime, cartoon, and games sector (ACG sector). According to sootoo.com statistics, the vast majority of Chinese web literature fans are male (76 percent). Furthermore, most share a taste for ACG culture as well as Anglo-American or Japanese-Korean TV series. This also plays into the hands of web portals and authors of online literature as regards further marketing of successful online works.

Writers’ Rich List

Today, some of the more successful web authors earn millions of yuan. China’s most commercially successful Internet author in 2015 was Tangjia Sanshao, as executive vice president of the Publishing Association of China Wu Shulin stated at the international conference “Story Drive,” organized by the Frankfurt Book Fair in China’s capital Beijing.

According to Wu, Tangjia Sanshao pocketed around RMB 110 million (US $16.5 million) last year from his online literature. Five other web writers received revenues of more than RMB 50 million, and more than 160 authors earned a yearly salary in excess of RMB one million.

But such success stories remain exceptions. “There are millions of authors on the web today,” Wu said. “Only a few make the breakthrough.” Among the reasons why is undoubtedly that characteristic features of the Internet, namely, its low threshold, prompt, non-bureaucratic distribution channels, potential to reach an immensely wide readership, and independence from traditional printed media boundaries, are both a blessing and a curse.

“There are still big discrepancies in quality,” Wu said. Critics hold that there is a high level of commercialization, and even pieces which, upon taking a closer look, turn out to be nothing more than clever advertisements.

Moreover, some experts bewail the absence of an advanced system of literary criticism for the online genre. So far, the tastes of the masses set the tone. “Some of the contents glorify violence or are questionable in other ways,” Wu said.

Another problem yet to be solved is that of intellectual property. “In the end, the function of traditional publishing houses as guarantors of quality remains indispensable,” remarked Jürgen Boos, president of Frankfurt Book Fair, on the margins of the “Story Drive 2016.” He added: “This also applies to the Chinese market.”

However, it is an indisputable fact that, since appearing at the end of the 1990s, China’s online literature has grown from a small niche genre not taken seriously for some considerable time into a promising and influential new sector of the country’s cultural industry. One reason for the success of China’s web literature is undoubtedly its potential for adaptation into movies and television series, or re-marketing in printed form.

Consequently, China’s web literature has long since hit the mainstream of the country’s Internet-centered readership. The future development of literary quality will finally depend on the qualitative demands of the targeted audience.

However, there seems little doubt that the online literature boom has created an exciting new field of experimentation, nurtured by ideas from those of China’s authors and readers who were born in the 1970s and after. This artistic playing field will likely act as inspiration for China’s cultural industry as a whole, and could also stimulate development of the cultural industry in the West.