Free Trade Zones for a More Open Market

By LI GANG

UNDER the background of enhanced economic globalization and multiple challenges to free trade, countries are generally opting for bilateral and multilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). These transactions remove trade and investment barriers and promote regional economic development, which explains the growing number of Free Trade Zones (FTZs). To adapt to the latest trends of economic globalization and further promote China’s opening-up, the Chinese government has accelerated its establishment of FTZs. Sticking to the cardinal principle of win-win and mutual benefit, China has built many FTZs with the aim of propelling common development of China and other countries and regions of the world.

China’s FTA Network

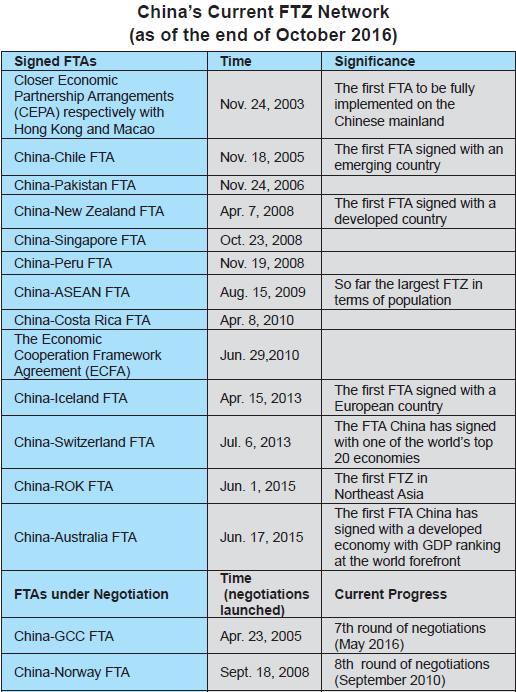

So far China has formally signed 14 FTAs, involving 22 countries and regions. Among them are the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangements (CEPAs), concluded between the Chinese mainland and, respectively, the separate customs territories of Hong Kong and Macao, in 2003. They are the first FTAs to be fully implemented on the Chinese mainland.

China has signed and implemented five FTAs with developing and emerging countries. They are: Chile, Pakistan, Peru, Costa Rica, and the Republic of Korea. China has moreover signed five FTAs with developed countries: New Zealand, Singapore, Iceland, Switzerland, and Australia. Among the latter five, New Zealand is the first developed country to sign an FTA with China, and Iceland the first European country to sign an FTA with China. The China-ASEAN FTA is currently the only multilateral one.

Besides, the Chinese mainland and Taiwan have signed the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA), which can be considered as a preliminary framework arrangement for an FTA negotiation.

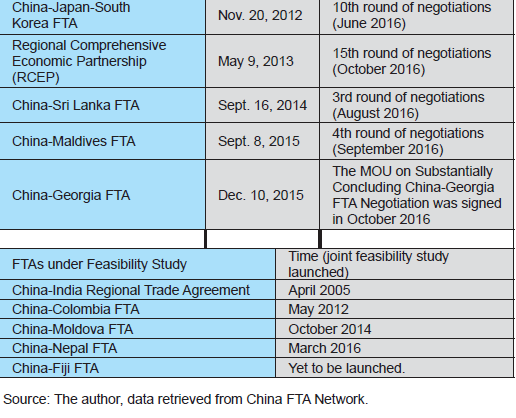

In addition to FTAs that have been officially signed, more FTA talks are in progress. They include the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP); the China-GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council); the China-Norway FTA; the China-Japan-South Korea FTA; the China-Sri Lanka FTA; the China-Maldives FTA; and the China-Georgia FTA. Moreover, China completed in October 2007 a joint study on the China-India Regional Trading Arrangement (RTA). The country also launched feasibility studies on the China-Colombia FTA in 2012, the China-Moldova FTA in 2014, and the China-Nepal FTA in 2016.

Benefiting Consumers

When established, the FTZs will substantially cut import tariffs, or even reduce them to zero. Domestic consumers may then buy quality imported goods at lower prices. For example, since establishment of the China-Australia FTZ, lobsters, steaks, and various wines produced in Australia, formerly only available in high-end hotels, are now within reach and affordable for everyday consumers.

The import tariffs on New Zealand dairy goods have also gradually fallen year-on-year. The bilateral FTA stated that China would progressively reduce tariffs on New Zealand dairy products from October 2008, and phase out tariffs on milk powder by January 1, 2019.

Thanks to the China-ASEAN FTA, Chinese consumers can now enjoy local fruits and snacks from ASEAN countries, such as fresh purple mangosteens, dragon fruit, and rice from Thailand, green bean cake from Vietnam, dried mango from the Philippines, Indonesian honeycomb cake, and coffee from Vietnam and Malaysia.

The China-Switzerland FTA stipulated that China would progressively lower tariffs on luxury watches and medical devices, year-on-year, and that China would reduce import duty on Swiss watches by 60 percent over 10 years. In 2014, the first year the agreement took effect, import duty on Swiss watches was cut 18 percent, and by around five percent annually in the ensuing years.

Foreign consumers in the FTA signatory countries and regions also gain the practical benefits of being able to buy products from China at lower prices.

Boosting Trade

After the FTZs have been established, member states will mutually reduce import tariffs. Therefore, both producers and consumers will be able to buy goods from their partner countries at lower prices, and this will expand trade among them.

The effect is clear from the China-ASEAN FTZ. According to Ministry of Commerce statistics, the bilateral trade volume between China and ASEAN has surged almost nine-fold, from US $54.8 billion in 2002 to US $480.4 billion in 2014. Mutual investment, meanwhile, expanded from US $3.37 billion in 2003 to US $12.2 billion in 2014 – an almost four-fold increase. China is now ASEAN’s largest trading partner, and the regional bloc is China’s third largest trading partner.

The signing in 2005 of the China-Chile FTA has significantly boosted bilateral trade ties. The trade volume between the two countries has increased around 8.4-fold, from US $7.1 billion in 2005 to US $34.1 billion in 2014.

China and Switzerland’s economies complement one another, and have a sound foundation for bilateral trade. Moreover, the FTA grants zero tariffs on 99.7 percent of Chinese exports to Switzerland, and 84.2 percent of Swiss exports to China – factors that add significant momentum to bilateral trade. Switzerland Global Enterprise (SGE) research projects an average annual growth in export volume from Switzerland to China of five percent. By 2028, the SGE predicts, Swiss companies will have saved about SF 5.8 billion (about € 4.8 billion) as custom duties are gradually phased out over a number of years.

Promoting Investment

FTZs will not only boost economic growth, but also make it easier for enterprises to invest. FTAs China has signed with various countries cover a broad range. They include elimination of tariffs and non-tariff barriers to facilitate free trade, rules to stimulate investment, competitive policies, intellectual property rights protection, environmental issues, and people-to-people exchanges, so laying the groundwork for expanded mutual investment. As the FTAs come into effect, therefore, their removal of barriers will boost mutual investment, as well as trade.

Since the China-Australia FTA came into force, for example, the two countries have accorded one another Most Favored Nation (MFN) treatment as regards investment. This means they provide each other the same preferential treatment as that enjoyed by their other economic and trade partners. The only proviso is that Australia will not in the future receive the same preferential treatment that China provides investors from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. Australia provides China with high-level investment treatment that is more or less equivalent to that accorded its other trade partners, such as the U.S., South Korea, and Japan, in the form of a negative list.

Meanwhile, Australia has dramatically reduced the threshold for Chinese parties’ investments in Australia, the exemption standard for investment examination having increased from AU$248 million to AU$1.078 billion. In order to protect the legitimate rights and interests of both parties’ investors, the FTA includes a dispute settlement mechanism. This provides, in the event of any dispute between the investor and the host country, certain remedies for the investor and a powerful system to guarantee their legal rights. It thus enhances investors’ confidence and assuages their worries.

According to Chinese Ministry of Commerce, by the end of 2014, Chinese businesses had invested US $74.94 billion in Australia, including direct investment of US $19.95 billion. Australia was thus China’s second largest investment destination only after Hong Kong. By the end of April 2014, Australia had cumulatively invested and established 10,428 enterprises in China, with actually used foreign capital of US $7.595 billion. The FTA stipulated that the two parties would promise one another a high level of opening-up of their markets, a commitment that is proactive in maintaining the current investment development momentum of both parties and expanding new investment fields.