By staff reporter ZHANG HONG

By staff reporter ZHANG HONG

IN June this year, the Beijing-based media company Golden Tara started shooting the film adaptation of the Tibetan epic, King Gesar. This RMB 500 million production is expected to reconstruct the exploits of the ancient hero through thrilling special effects and mesmerizing scenes that could rival the likes of The Lord of the Rings and Troy.

Airing Brings More Publicity

King Gesar, dating back to the 11th century, is a lengthy Tibetan epic poem performed in the form of storytelling and singing. It was inscribed by UNESCO as a world intangible cultural heritage in 2009 and enjoys world fame as the “Homeric hymn of the East.”

With backing from the China Cultural Heritage Foundation and China Thangkas Culture Research Center, Beijing Golden Tara Film Co., Ltd is now working on a film about the legendary Tibetan hero. To bring a work that has been passed down orally for centuries to the silver screen to be viewed by billions of people globally is “an effective method to promote Chinese culture nationwide and worldwide,” according to Golden Tara President Deyang.

The longest epic in the world, King Gesar is about the hero’s combat with demons to free the oppressed and rescue his mother and wife from hell. Studies of the work constitute an independent sector of Tibetology – Gesarology – whose researchers are found worldwide.

A mounted Tibetan Opera play about King Gesar in Golog Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province.

Written using more than 20 million characters over 120-plus volumes, King Gesar is longer than all world-renowned epics combined. Such a size is challenging for a film adaptation that normally runs for a couple of hours. It is, however, the life ambition of Jampel Gyatso, an ethnic literature researcher with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a Gesarological expert.

According to Jampel Gyatso, the Chinese government has invested huge human and financial resources to preserve this oral Tibetan cultural heritage over the past decades. To date more than five million copies of King Gesar have been printed, enough for one copy for every Tibetan in China.

It is the shared belief of Deyang and Jampel Gyatso that a splendid cultural heritage like King Gesar should be shared by all humankind and not restricted to one ethnic group. As a leading figure in the study of the epic and China’s first Tibetan professor for doctoral programs, Jampel Gyatso took a major role in the planning and production of the upcoming film.

“Movies can to certain extent overcome language barriers, and they are, therefore, one of the best media to introduce Chinese culture to the world,” said Deyang.

Despite the remarkable progress China has made in the research of King Gesar over the past years, the country lags behind the U.S. and Europe in retrofitting ancient epics into various art forms to fully tap their cultural significance, said Jampel Gyatso.

There is a huge market for epic movies. Many ancient stories such as those by Homer and Indian epics have been rendered into film, TV series, and other art forms that are well received. The 2003 Hollywood blockbuster Troy, loosely based on The Iliad, was viewed by hundreds of millions of people globally, and was among the highest grossing films of 2004. Hot on its heels came Der Ring des Nibelungen and Beowulf. The three made a big splash on the international film market. But in China not a single indigenous saga has made it to the big screen.

The Sertar Tibetan Opera Troupe.

When Jampel Gyatso studied at Harvard as a visiting scholar over a decade ago, someone there suggested to him that China made a film of King Gesar. In his later visits to India he was impressed that its prolific film industry had produced three or four films based on Indian ancient epic poems The Ramayama and The Mahabharat. These experiences enhanced his desire to bring the Tibetan saga to the silver screen.

“All the four classical novels of Chinese literature have now had film and TV adaptations. King Gesar must join the club and in doing so, highlight the fact that China is a big family of different ethnic groups,” said Jampel Gyatso. He hopes that the film he is working on will run for the Academy Awards, which have seldom been won by Chinese filmmakers.

Time Is Ripe

Hegel once said that China had no national epic; Jampel Gyatso’s 30-plus years of study of King Gesar strongly refutes this opinion. The Tibetan epic is actually the longest in the world, longer than The Epic of Gilgamesh, The Iliad, The Odyssey, The Ramayana and The Mahabharat combined. “The study of King Gesar allows China and the world at large to take another look at the people that created it,” said Jampel Gyatso.

China has cultivated a number of King Gesar researchers of both new and older generations and different ethnic groups. What’s more, historical sites and objects related to King Gesar have been afforded better protection, including the Lion and Dragon Palace in Golog Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province. A memorial hall and a cultural center dedicated to the legendary hero were built in Dege County and Sertar County of Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province respectively, and there is an equestrian park named after the ancient king in Marqu County of Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Gansu Province. In these regions of dense Tibetan populations, King Gesar features prominently in local development strategies and cultural programs.

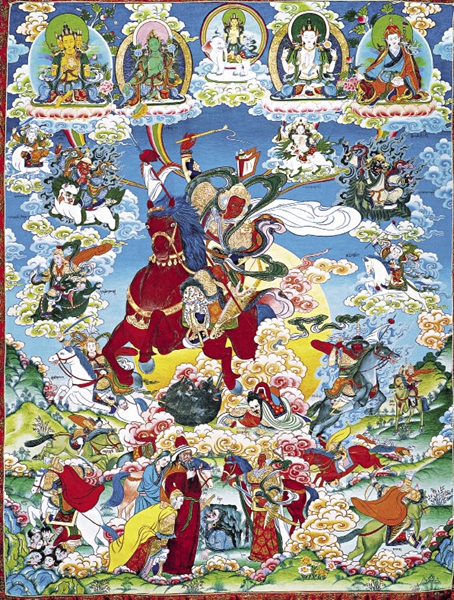

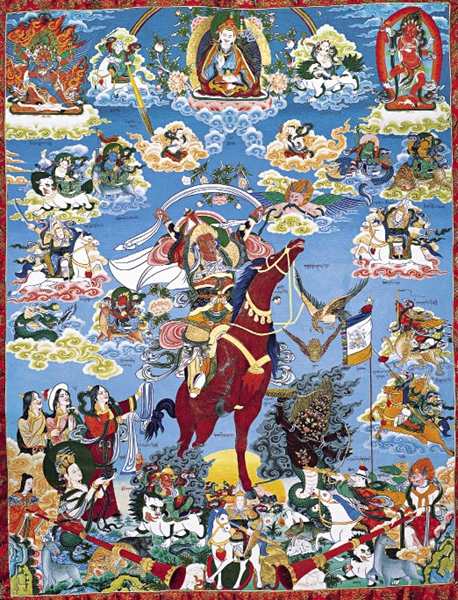

A Thangka painting of King Gesar out on an expedition.

King Gesar culture reached a new peak after China adopted opening-up and reform policies, as evidenced by the great number of works in the forms of Tibetan Opera, dance dramas, songs, music, and even Peking Opera. “These all provide fodder for the King Gesar film,” said Jampel Gyatso.

Quality First

The film adaptation revolves around three stories chosen from the lengthy epic that are set in contemporary narratives to make them more appealing to today’s audiences. As the life of King Gesar is celebrated for his triumphs over demons and evils, the film is understandably of the fantasy genre. Deyang, however, has pledged that she will not let fantasy gimmicks and special effects overshadow the epic nature of this grand production. “We are not making a fast-food work; quality always comes first,” she declared. “We have the utmost reverence for this figure. Though we are not settled yet on what more we can do for the production, we are clear about what we will never do.”

As to the criticism of the homogenization of Chinese fantasy films, Deyang is confident that King Gesar is the new bonanza for China’s filmmakers to explore after they have almost exhausted resources from such ancient literary classics as Journey to the West and Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. “King Gesar consists of a good number of stories and characters that construct intricate, dramatic plots and relations. Once this rich mine is exploited, the whole domestic fantasy film sector will be boosted,” said Deyang confidently.

When selecting the actor for the role of King Gesar, Golden Tara General Manager Jiang Hong was impressed that many Buddhist candidates offered to play the role for free. “That’s the power of our legacy.” He acknowledged that the film must be first of all entertaining, as enticing people into the cinema is the most important way to get the story known as widely as possible. To ensure the appeal of an old tale to young people, who constitute the majority of film consumers, Golden Tara will recruit the post-production team behind The Lord of the Rings.

Following the film, the company plans to develop merchandise, including cartoons and computer games. It is even considering a King Gesar-themed cultural park.

The film will be shot in Tibetan areas across China and sites in other countries. It is expected to debut in early 2018 in three languages – Mandarin, Tibetan, and English.

The production team believes it’s their duty to represent this epic, which is widely read and sung among Tibetans, on the big screen to be known by more people. “We will feel nothing but regret if the story of King Gesar is lost among later generations,” said Jiang Hong.