Mukeng: Sea of Bamboo

Mukeng: Sea of Bamboo

By staff reporter LIU YI

CROUCHING Tiger, Hidden Dragon was the dark horse in the 73rd annual Academy Awards race in 2001. It unexpectedly picked up four Oscars: for best foreign language film, best cinematography, best original score and best art direction. American Chinese director Ang Lee was catapulted to international fame, and the stunning beauty of Mukeng, one of the locations, was unveiled to a worldwide audience.

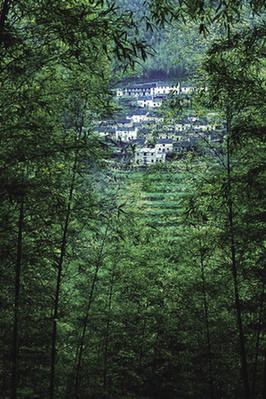

Located on the western tip of Huangshan City, Anhui Province, Mukeng Village rests in a six-km-long valley. It is 25 km south of the famed Huangshan Mountain, and five km east of Hongcun, a small village listed as world cultural heritage for its architecture and folk culture. Covered by bamboo forest, the valley is like a giant emerald. Sometimes the winds bend the treetops all the way into the recesses of the valley, like waves on a sea of green.

In the movie, a bamboo forest featured in a decisive battle – two swordsmen fought a contest on the treetops. The scene impressed many people and attracted more and more travelers to Mukeng, as well as painters and photographers.

|

|

|

Mukeng is enbedded in a sea of bamboo. |

The Bamboo Life

Embedded in the middle of the green sea is a small village. In the distance, the houses, with sparkling white exteriors, look like white rocks in an open sea. There are only 24 households in Mukeng, all sharing the same surname, “Fu.” The clan has lived here for generations. In contrast to the houses in Hongcun, the Fu family obviously favors simple dwellings with clean lines rather than sophisticated and decorous houses. Stone slabs pave roads that trace the hillside, connecting each household to its neighbors above and below. For people new in town, the village is something of a maze. Spring water streams down to fill every household’s fish pond, and nourish the vegetable patches and tea plantations in front of the village. Water conduits are often made of split bamboo trunks with nodes removed and connected to each other end to end, like open culverts. These natural water pipes introduce spring water directly to village kitchens.

“Live in a mountain, live on the mountain.” This old Chinese saying reminds us mountain people can live on the productions of their surroundings. The villagers eat with bamboo chopsticks, sweep with bamboo brooms. On rainy days, they put on bamboo hats, while in good weather they sit in bamboo chairs to bask in the sunshine. They can see the sea of bamboo everyday, and hear the sounds when the wind blows through leaves. In a practical emergency like a cash shortage, they can chop down some bamboo trees to sell in the market. Bamboo and life are inseparable in Mukeng.

It seemed natural to see tourism develop once Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon introduced this small village to the world. Villagers refurnished their houses for home stays. The home inn lets the traveler experience the self-sufficient life of locals. They share the same food with host families, see how to chop down bamboos, dig up bamboo shoots, pluck tea leaves and raise chickens. The largest of these accommodates 50 guests, while the small ones just rent their one or two spare rooms. In the biggest home inn, Bamboo Villa, a room costs no more than US $10 per night (excluding breakfast). Other home inns are priced lower and vary in terms of living conditions. As there is only one grocery store, those who plan to stay for a couple of days should bring along anything they need and can’t buy locally.

Despite an influx of curious visitors, Mukeng is still quiet compared to nearby Huangshan Mountain and Hongcun. Packaged tour groups are rarely seen here. Most of the guests are independent backpackers, but some families like to spend a weekend as well. When travelers get off the bus at the end of winding mountain roads, they need to walk for about ten minutes before catching sight of the first household in the village.

Treats to Tributes

Travelers to Mukeng will soon befriend the humble bamboo shoot; they appear in almost every dish, especially in winter and spring. Bamboo shoots are a delicious treat when stewed with ham, in a hotpot or simply stir-fried with meat. The surplus of bamboo shoots are usually dried and used the following year. Dried shoots stewed with pork ribs are a popular dish among people of the mountain.

Bamboo is far more than a menu item in China. The juice extracted from them is a traditional medicine for coughs and sore throats. Zhuyeqing, or Bamboo Leaf Green, is a famous wine with a history of 2,000 years. Bamboo leaves give the wine a special aroma and wonderful taste. Bamboo fungus, a kind of parasite living in synergy at the bottom of a bamboo, is delicious and nutritious. Dubbed “queen of fungus,” it used to be a tribute prepared for emperors.

The days around winter solstice are prime time for digging up bamboo shoots. Harvesters will work from early morning till sunset, even late into the night. As bamboo shoots hide underground all winter, it takes experience to find them and gently uproot them with hoes. Rookies usually return empty handed while veteran farmers can net as many as 50 kg a day. Digging up bamboo shoots not only benefits the cooking pots of harvest time and the store rooms, but ensures a better timber harvest in the coming year. In the winter bamboo shoots seem small and harmless enough but large numbers of shoots will crowd each other out in the spring, and limit growth. Thinning them out helps the rest grow tall.

In spring, the plentiful rain wakes up the sleeping bamboo shoots, and their breath-taking emergence from the ground begins. They grow so fast that in a dozen days they can be as tall as old bamboos. At mid-night, you can clearly hear the rattling of trunks as they grow more nodes. An adult bamboo is about 10 to 20 meters high. In three months, it will have a diameter as wide as a rice bowl. In a year, it can be used as timber. With forests generally on the decline nowadays, bamboo has become an important alternative resource, with bamboo stands being extended, especially into mountainous areas. Tourism spots named “sea of bamboo” have popped up in many southern provinces like Jiangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang and Sichuan.

There’s bamboo and there’s bamboo. Those growing in Mukeng are mao bamboo, the most widely distributed timber-type bamboo in China. In ancient times, mao bamboos were used to make combat weapons and tools for farming and fishing. In the warm and humid southwest provinces, they are important construction material, creating comfortable houses with natural ventilation. In southern China, through which numerous rivers flow, bamboo rafts are a common vehicle. Now bamboos are manufactured into floor boards, or furniture. Their fibers can even be used to make clothes or a variety of handicrafts.

Bamboo handicrafts are an old trade in China too, and still popular in some villages or towns. The craftsman will slice bamboo into thin strips and weave them into a mat or toys. The strips dance in the hands of the craftsman and become a new packing bag, cage, or any kind of basket in a half day. He will solemnly write down his name and the date on the bottom of his productions.

Roots of Bamboo Culture

So widely used in Chinese society, the bamboo has been an important motif in music, poetry, calligraphy and painting. Many traditional musical instruments are made of bamboo, including wind instruments like the dizi and xiao, and plucked instruments like the zheng. Bamboo is also used as a tonemeter throughout history. In ancient China, bamboo was synonymous with music, so instrument artists were called “bamboo people.”

As early as 600 BC, Chinese began to write on bamboo strips with brush pens. The strips would be strung together to make a kind of codex. This was the style of book used to record the thoughts of Confucius and other ancient philosophers, as well as much historical data. This kind of “book” was superceded by the invention of paper. However, the demand for bamboo didn’t decline, as it was the raw material for papermaking and constituted the key component of brush pens.

Bamboo itself symbolizes China’s civilization. Its characteristics embody virtues long admired in the Middle Kingdom. The leaves droop slightly, representing modesty; it stands straight, showing strength. Comparing a man to the bamboo amounts to the highest praise of his character. In the third century AD, seven scholars of the cynical school chose to live in retreat and withdrew to a bamboo forest. Dissatisfied with government and society, they spent days making poetry, preaching or drinking. They were called the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Forest. Later ages saw a lot of people comparing themselves to bamboo, like painters Zhao Mengfu (1254-1332) and Zheng Banqiao (1693-1765).

For thousands of years, numerous myths, poems, calligraphic works and paintings were themed on bamboo. Great writer Su Shi (1037-1101) took delight in painting it, but his friends found it strange that it took so much more time for him to observe them than to paint them. “I paint the bamboos in my mind and then commit them to paper,” he explained. The anecdote later became an expression for a well-thought-out plan.

You can go without meat for dinner, but cannot live without bamboo, a poem of Su’s cautions. He believed that a shortage of meat would merely leave people thinner, whereas an absence of bamboo around your house would make you vulgar. The quartet of bamboo, plum blossom, orchid and chrysanthemum, are called the Four Gentlemen. For their resistance to severe weather conditions, the bamboo, pine tree and plum blossom are called the Three Friends of Winter.

When you wake up on a summer morning in Mukeng, the soft sounds made by gentle breezes in bamboo leaves reaches your ears first, along with the gurgles of springs: the most beautiful morning calls you’ve ever heard, but just another day in paradise for the people of Mukeng.

Services

Economy

- Eco-agriculture and Eco-tourism Power Nanchang’s Green Development

- Balance Environmental Protection and Economic Prosperity – Nanchang Looks to European Technology for Green Development

- Sustainable Growth Requires Wiser Energy Use

- Chinese Economy: On the Path of Scientific Development

- China's Economy over the Last Ten Years