By LIN MINWANG

By LIN MINWANG

DESPITE its neighboring countries finding themselves in complicated and often volatile situations, China still markedly extended its influence in the Asia-Pacific region during 2016. Issues involving the U.S. (such as the South China Sea dispute and the Obama administration’s pivot on Asia strategy) became key factors affecting China’s neighborhood diplomacy over the past year. As both parties exerted excellent control over the situation, no confrontational diplomatic moves occurred. With Donald Trump set to become the 45th President of the United States in 2017, China’s neighborhood diplomacy will undoubtedly face new challenges; China will continue, regardless of any changes, to maintain strategic focus and patience, so as to build a favorable neighboring environment.

China’s Increasing Influence

Transfer of power in several countries in the Asia-Pacific region did not impact on their bilateral relationships with China, but actually improved them.

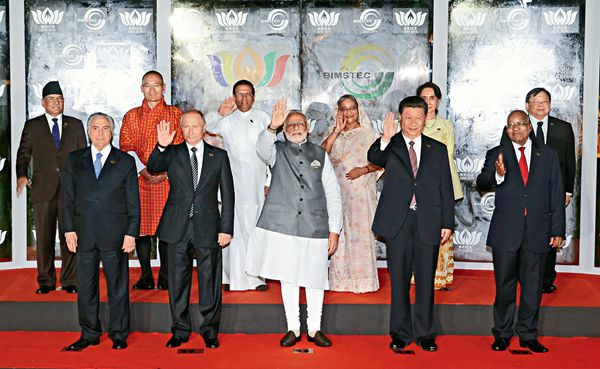

The outreach summit between leaders of BRICS countries and member states of the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) was held in Goa, India on October 16, 2016.

On March 31, the new government of Myanmar, led by the National League for Democracy, took its oath of office and formally started their administration on April 1. The head of the party, Aung San Suu Kyi, made China the destination of her debut state visit in August, fully demonstrating the importance of China in its diplomatic relations. Then, in late October, Myanmar’s Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing also paid a visit to China.

In late January 2016, at the first plenum of the 12th Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam, the Party’s new leaders were elected, with Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong at the head. The former Prime Minister of the Vietnamese government, Nguyen Tan Dung, failed to gain a place on the Party’s Central Committee or the Political Bureau of the Central Committee. Therefore, it was generally regarded that Vietnam’s moderate political sect had won.

In mid-September, the new Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc made his first visit to China after assuming office, which significantly increased stability in the South China Sea.

In late May, Rodrigo Duterte was elected as the new President of the Philippines. Duterte’s state visit to China in October thawed the icy bilateral relationship after the South China Sea arbitration and also forced changes to the American Asia-Pacific rebalancing strategy.

Some unexpected political incidents also occurred in the region last year, but did not upset political stability in the countries involved. Bhumibol, the King of Thailand, died on October 13. Many people speculated that civil unrest would sweep through Thailand, but in reality the situation is much more positive. Uzbek President Islam Karimov died of an illness after 27 years in power on September 2. Despite fears for political stability in Central Asia, no civil disorder occurred and the country is running as normal.

Soft Landing on the South China Sea Issue

As China’s policies regarding its claims on the South China Sea are gaining increasing support from its neighboring countries, this red-hot issue is slowly being cooled down. Despite its adverse impact on China’s relations with neighboring countries, during the whole process China’s stance has won greater understanding and support from other countries in the region.

The commander of the People’s Liberation Army Navy, Wu Shengli, met visiting U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, John Richardson, in Beijing on July 18, 2016. They exchanged opinions about maritime safety, the South China Sea issue in particular.

When an arbitration award was issued on July 12, a handful of countries such as the U.S., Japan, and Australia advocated its “binding force.” The decision, however, has not won support from ASEAN countries. At a meeting of ASEAN foreign ministers on July 24, no agreement was reached regarding the arbitration award.

In addition, both the UN and the International Court of Justice were eager to stress that they had no connection with the tribunal. On July 13, the UN stated on its official microblog that it was not affiliated with the arbitral tribunal. The International Court of Justice in The Hague also declared that it had not been involved in the “South China Sea arbitration case.”

All parties involved in the dispute, including Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia, have been cautious in their attitude towards the award, which suggests that it is not an appropriate way of dealing with the South China Sea issue.

The dual-track approach proposed by ASEAN countries and China to cope with the issue should be the chosen approach, namely settling disputes peacefully through negotiations and consultations between the states directly concerned on the basis of respecting historical facts and conforming with international law. The peace and stability in the South China Sea should be maintained with the joint efforts of both China and ASEAN countries.

Integrated Asia-Pacific Economy

China’s proposals and initiatives for cooperation in the region are timely and expected to make headway. This signifies China’s increasing capacity for crafting new trade and investment rules in the Asia-Pacific region.

Gwadar Port, Pakistan, formally went into operation on November 13, 2016, opening a new trade route along the Belt and Road.

China’s proposal to integrate the Asia-Pacific economy took a remarkable step forward in 2016. Xi Jinping expounded the proposal at the APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting in Lima on November 19, saying that China will be deeply involved in the process of economic globalization, support a multilateral trading system, advance the establishment of free trade zones in the Asia-Pacific region, and push forward negotiations on Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

The U.S. President-Elect, Donald Trump, declared that the U.S. would exit the Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement. As a result, China’s proposed Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) became one of the key topics at the APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting. The summit approved a research report on collective strategy for Asian-Pacific free trade zones submitted by the APEC ministerial meeting, intending to make free trade zones a major platform for an integrated Asia-Pacific economy in future.

The ASEAN-led RCEP is also expected to make headway. Just prior to the summit, Peru declared it would start negotiations about joining the RCEP. The advancement of both FTAAP and RCEP signifies that China is starting to play a leading role in integrating the regional economy.

Major progress was also made in the Belt and Road Initiative during 2016. Gwadar Port formally went into operation on November 13, turning the concept of the China-Pakistan economic corridor into reality. It is a new milestone for interconnectivity in South Asia. The Port of Colombo in Sri Lanka resumed construction in June after suspension due to internal politics.

In addition, interconnectivity advocated by China’s Belt and Road Initiative saw great advancement in Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and South Asia, evident in policy coordination, facilities connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds. China’s economic power is turning into a capacity for shaping regional order.

Safe and Stable Future amid Uncertainties

Of course, China’s neighborhood diplomacy also suffered some adverse factors in 2016. On January 6 and September 9, North Korea carried out two nuclear tests, defying the whole world and exacerbating the situation in the Korean Peninsula. In response, on July 8, South Korea and the U.S. declared that a THAAD (Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense) anti-missile system would be deployed in South Korea by the end of 2017. But the THAAD system is far beyond the defense needs of the Peninsula, and will disrupt regional stability.

Moreover, two terrorist attacks were carried out against Indian military bases in 2016. India put the blame on Pakistan, thus injecting further hostility into their bilateral relationship. As an adamant supporter of Pakistan, China was rebuked by India, who accused China of being biased towards Pakistan; this dampened China-India relations to some extent.

As it stands, China’s peripheral situations are still changing and will face multiple uncertainties in the coming year. The most critical factor will be Donald Trump’s foreign policy on Asia. His claims during the presidential campaign have already impacted on the diplomatic policies of China’s neighboring countries.

China still needs to give full consideration to American factors and put greater importance on developing China-U.S. relations when considering its relations with neighbor states. At the same time, China should combine its principle of stability with flexible operations in its neighborhood diplomatic practices. China’s experience in dealing with the South China Sea dispute shows that as a regional power China has the responsibility to provide more public resources for the region but that it also needs to make it clear to neighboring countries that it will not be bullied.

Last but not least, China should lead the region towards establishing a new type of safety architecture, reflecting regional needs, conforming to the interests of related parties, and widely received by them, so as to cope with the jostling of growing superpowers brought about by the adjustment of the Asia-Pacific geopolitical landscape.

The common, comprehensive, cooperative, and sustainable security strategy for Asia advocated by China could constitute the ideological foundation of the architecture. A composite, multi-level, and diversified security network should be chosen. The most critical point is to form an effective operational mechanism, which is expected to play a key role in maintaining regional security and solving regional crises.

LIN MINWANG is a research fellow at the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University and guest researcher at the Collaborative Innovation Center of South China Sea Studies at Nanjing University.