By JOHN ROSS

By JOHN ROSS

CHINA’s 13th Five-Year Plan running from 2016-2020, presented to this year’s National People’s Congress, sets the framework not only for China’s domestic development but thereby for other countries’ economic interaction with it. Consequently, it is important for other states to accurately judge the main effects that continuation of China’s reform and opening-up process will have on them. The key trends confirm China will continue to show the greatest prospects for international cooperation of any major economy.

John Ross is a senior research fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. From 2000 to 2008 he was director of economic and business policy in the administration of Mayor of London Ken Livingstone. He previously served as adviser to several major international mining, finance and equipment manufacturing companies.

The first key point is that the 6.5 percent minimum annual GDP growth target over the Plan’s whole period is more important for China and other countries than 2016’s individual 6.5-7.0 percent target. Some commentators have suggested that while China may achieve a 6.5 percent growth target in 2016, this will be followed by significant slowdown – to 5.0 percent or below by 2020. Should that occur, China would drift towards, or in the worst case scenario fall into, the “middle-income trap.” The Plan’s arithmetic makes clear China is not prepared to let this happen, while the key features of China’s economic structure show there is no reason why it should.

The 13th Five-Year Plan’s decisive target is to achieve a “moderately prosperous” society – in numbers doubling China’s GDP between 2010 and 2020. Growth in the first half of this decade averaged 7.8 percent. Therefore, to achieve the decade’s target average, annual growth throughout 2016-2020 must equal at least 6.5 percent. As 2016’s target is 6.5-7.0 percent this means no significant slowing is acceptable in the Plan’s later years.

More important than verbal commitment is that China’s fundamental economic parameters show this target can be achieved – China’s fixed investment is over 40 percent of GDP, more than double that of the U.S., while statistics confirm China’s efficiency of investment in generating growth is higher than the U.S.

This means China will maintain its present position as the world economy’s strongest development point throughout the Plan period. The U.S. GDP growth in 2015 was 2.4 percent, in line with U.S. average annual growth for the last 20 years. Even assuming U.S. growth does not slow further, and it has been decelerating for several decades, in the next five years China’s economy will expand by 37 percent compared to the U.S.’s 13 percent.

The second key impact for other countries is created by the combination of China’s rapid growth with China being a more open trade economy than the U.S. According to the latest internationally comparable data, trade constituted 40.1 percent of China’s GDP compared to 30.1 percent for the U.S. China’s greater openness means its growth generates proportionately more increases in international trade than equivalent U.S. growth.

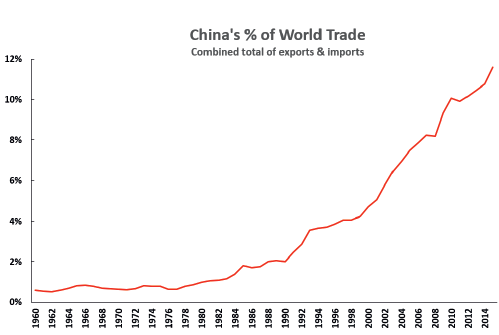

In order to accurately grasp these trade trends, it is important to correct misunderstandings caused by the fact the dollar value of all major economies trade is currently declining due to the global fall in commodity prices – the latest IMF data show trade declining US $3.5 trillion, or 11 percent, year-on-year. But China’s world trade share has expanded as it suffered less from this than other major economies. As Figure 1 shows, the latest IMF data show that China’s share of world trade has reached its highest ever level. China is continuing to out-compete and out-trade other economies – consolidating its position as the world’s largest goods trading nation.

But if China’s global position in growth and trade continue well-established trends, there are key new factors which will affect other countries as China makes the transition from a “medium income” economy by World Bank standards towards a “high income” economy. Some, such as China becoming the world leader in renewable energy, will have a major indirect effect on other countries via their effect in fighting climate change. But two directly economic processes particularly affect other countries.

Source: Calculated from IMF Direction of Trade Statistics, 2015 data is for first 10 months

First, China is no exception to the rule that all major economies internationalized first via trade and only later via foreign direct investment (FDI). But China has unparalleled financial resources to develop FDI. China’s US $3.2 trillion foreign exchange reserves are the world’s highest. China’s domestic savings, the raw material for its financial system, have now far overtaken the U.S. – World Bank and U.S. data show China’s 2014 savings at US $5.2 trillion compared to the US $3.3 trillion of the States.

Globally unmatched financial firepower allows China to rapidly ramp up its annual outward FDI flow from under US $20 billion in 2006 to US $118 billion in 2015, to be the driving force behind the Belt and Road Initiative, and to lead multilateral initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank (BRICS bank). Simultaneously, China’s domestic market’s rapid expansion attracted US $119 billion inward FDI in 2015, with 61 percent going into services. China will therefore play an increasingly large role in global bilateral and multilateral FDI.

A second decisive trend is China’s technological upgrading and the priority given to developing innovative capacity. It is a romantic myth that innovation is due to creative culture or “garage start-ups” – the latter failing to mention what such garages are connected to! As Zotan Acs noted in his classic study of U.S. innovation: “When one asked the question, ‘What makes Silicon Valley unique’ the discussion usually came back to one great institution – Stanford University. It is conventional wisdom that Silicon Valley and Route 128 owe their status as centers of commercial innovation and entrepreneurship to their proximity to Stanford and MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology].”

The Five-Year Plan will raise China’s R&D spending to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2020 – almost equalling the U.S.’s current R&D spending as a proportion of GDP. It is this huge resource allocation that powers China’s innovative ability. It ensures that although China will switch out of industries fundamentally dependent on very low wages, it will increasingly gain competitiveness in medium technology and parts of high technology industries – crucially affecting other countries. China will increasingly export higher value products while importing products produced with low labor costs. Simultaneously consolidation of China’s lead in “cost innovation” and ability to achieve competitive prices by technological and managerial innovation means global companies will increasingly have to locate research facilities in China.