“Comfort Women” Merit Remembrance

By staff reporter LI WUZHOU

On August 6, Navi Pillay, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, urged Japan to produce a comprehensive, impartial and lasting resolution on the issue of wartime sexual slavery, the so-called “comfort women.” She lamented a report released by the Japanese government on June 20 that said it “was not possible to confirm that women were forcefully recruited.” In appealing to Japan, Pillay recognized that such a statement would cause tremendous agony to those female victims.

On July 24, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) published concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Japan, in which it demanded the Japanese government recognize its responsibilities and ascertain the perpetrators’ crimes. The OHCHR also pointed out the importance of fully including the facts concerning “comfort women” in Japan’s history textbooks.

China Today conducted an exclusive interview with Professor Su Zhiliang to find out more about the OHCHR’s petition to Japan, and China’s view on the “comfort women” issue. As director of the Comfort Women Research Center at Shanghai Normal University, Professor Su initiated China’s application for the registration of historical documents on “comfort women” in the Memory of the World Program in June 2014. This international project, launched by UNESCO, aims to preserve documentary heritage.

|

|

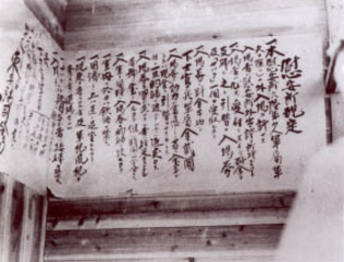

Yangjiazhai “Comfort Station” regulations issued by the command of Japanese army in Shanghai. |

Searching for the Survivors

It was by chance that Su got into research on “comfort women.” In 1992, he went to the University of Tokyo as a visiting scholar to research the history of narcotics in China.

During a casual conversation with one of his Japanese counterparts, Su learned that the first “comfort station” was established in Shanghai. In the past the Japanese government had deliberately concealed the issue of “comfort women”; but by 1992, the subject had attracted increasing attention worldwide.

After returning to China, Su immediately started an investigation into the issue. But he faced multiple difficulties: The Japanese army had destroyed many relevant documents and files prior to the capitulation; few people had paid attention to the issue for quite a long time; most victims had passed away and those that were still living and their descendants were unwilling to talk about the painful experience for various reasons. However, Su persevered with his research and eventually found more than 100 victims who were willing to make their experience public. Some of these brave women’s stories are recounted below.

Tan Yadong, who lives today in Wanru Village of Nanlin Township in Baoting Li and Miao Autonomous County, Hainan Province, said that she remembered a girl who became pregnant after being raped by Japanese soldiers. On discovering the pregnancy, the soldiers tied the girl to a tree and stabbed her stomach with bayonets and forced other “comfort women” to watch. Tan told the investigator working for Su that the horrific scene had plagued her dreams at night to date.

Yang Shizhen’s life changed forever when she was kidnapped and held at a “comfort station” for seven days aged just 16 years old. Following her ordeal, she suffered mental disorders and double incontinence. Zhang Xiantu was forced to become a “comfort woman” at 17 years old. Whenever she saw Japanese soldiers approaching she would tremble with fear and could not stop shaking. Such is the potency of this painful memory that her hands still shake today. Chen Yabian has an eye problem: Her eyes constantly water due to an injury sustained at the hands of Japanese soldiers as she tried to resist their violation.