China and Its Neighbors March Onwards Interdependent

By DONG CHUNLING

DURING the year 2012, China and its neighboring countries entered a somewhat complicated diplomatic environment. Despite challenges, the situation as a whole remained stable. The center of gravity in world economy having shifted from West to East, there are now unprecedented opportunities for Asian countries to rise.

|

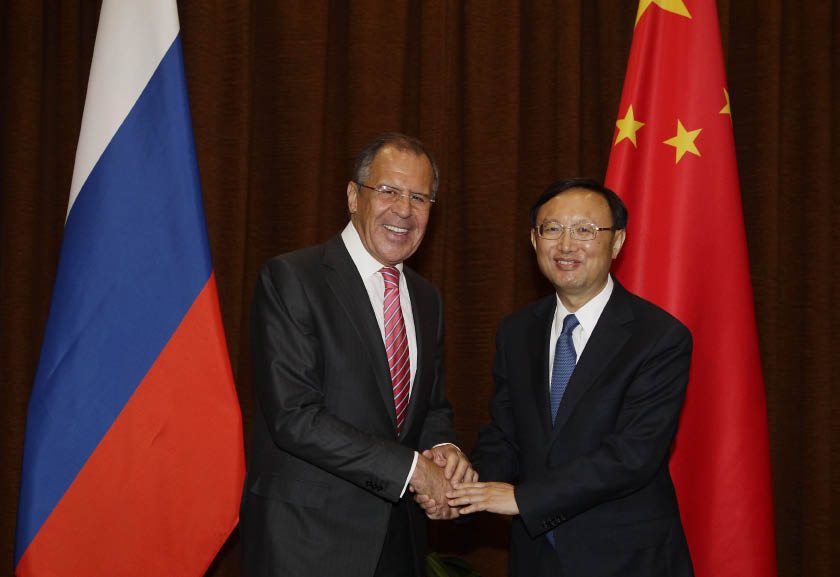

| Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov with Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi during his May visit to China. |

Meet Challenges Together

In 2012, China welcomed the new generation of political leaders, as the governments of neighboring Russia, Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK) entered overlapping election transition periods, leading to two extremes of foreign policy. One was that of preoccupation with domestic affairs and little effort towards diplomacy, adopting instead a wait-and-see attitude that diminished regional influence and created a power vacuum. The other was apparent in opportunistic provocations in efforts to gain political capital. The purchase of the Diaoyu Islands, masterminded by Tokyo Governor Shintaro Ishihara, and Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda’s “nationalizing” of the Diaoyu Islands are examples.

Despite mounting challenges, the surrounding diplomatic environment has remained largely stable. In Northeast Asia, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and ROK experienced intensified conflicts and constant friction after the death in December 2011 of DPRK leader Kim Jong Il, and the DPRK nuclear issue continued to simmer. The country nevertheless smoothly entered the Kim Jong Un era. Peace on the peninsula thus withstood a major test. In Southeast Asia, the South China Sea disputes highlighted problems among China, the Philippines and Vietnam. Cooperation between China and ASEAN nonetheless advanced. The U.S. and the Philippines propelled the Code of Conduct (COC) in the South China Sea but encountered setbacks. ASEAN remained impartial on major strategic issues, showing preference for neither China nor the U.S. In South Asia and Central Asia, meanwhile, the U.S.-Pakistan relationship deteriorated. The regional situation will undoubtedly see further turmoil after the U.S. army’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. International terrorism, however, underwent comprehensive contraction. Strengthening relationships among China, Pakistan and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) have moreover promoted regional peace and development. The East China Sea and South China Sea issues have been acute. The U.S. made moves to strengthen its relationships with its allies and with India, Vietnam and Myanmar to balance China’s influence. Cross-strait relations, however, have shown a positive trend that promises to grow in the wake of Ma Ying-jeou’s re-election. In the north, the strategic partnership between China and Russia strengthened; the two countries experienced the best bilateral period in their history.

Compared with the past, China’s surrounding environs in 2012 appeared more subtle and complex, but this is no cause for pessimism. Changes that have occurred are due partly to the overlapping effects of elections and partly to the eastward shift of the U.S.’s strategic center of gravity. Chinese political elites, meanwhile, underestimated the external influence of China’s rise. These growing pains need to be resolved in the near future through a more positive attitude.

External Reasons: Eastward Shift of Center of Gravity of U.S. Strategy

The year 2012 witnessed a comprehensive eastward shift of the U.S.’s strategic center of gravity. Raised in 2010, this diplomatic strategy was officially implemented at the end of 2011, when Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and U.S. President Barack Obama paid an intensive series of visits to the Asia-Pacific region. In 2012, the U.S. government took political, diplomatic, economic, and military actions stemming from this strategy with the aim of achieving a comprehensive arrangement in the region. China was just one of many factors driving this strategic shift, the eastward shift of global power being the foremost, deciding factor. The decline of the Western world and the rise of emerging countries moved the centers of international politics and economics from West to East and from North to South. As the U.S. and European countries became mired in the financial crisis and chaos reigned in the Middle East, the relatively stable Asia-Pacific region became a source of vigor in the post-crisis era. The U.S., Russia, India, Australia and other countries set their sights on it with a view to competing for the dividends of its development. The second factor proceeded from the U.S.’s domestic political and economic situations. A decade of anti-terrorism plus the financial crisis had debilitated U.S. economic growth. Financial reform lagged behind, employment prospects were bleak, social conflicts were prominent, and anxiety pervaded society. Barack Obama needed to find a bonus that would boost confidence in the economy and secure his re-election. Sharing in the Asia-Pacific economic dividends was the inevitable choice. The objective need to shape regional order constituted the third factor. The past 10 years have become known as “the lost decade” in the U.S. Preoccupied with anti-terrorism and two wars, America overlooked its role in the Asia-Pacific region. This resulted in a decline of regional leadership almost to the extent of exclusion. Asia’s integration, meanwhile, progressed, led by preparations for the 10+1 (ASEAN plus China), the 10+3 (ASEAN plus China, Japan and ROK), the China-Japan-ROK Free Trade Zone and the East Asia Summit. The rapid rise of China’s influence posed a comprehensive challenge to U.S. regional leadership. The U.S. strategic adjustment was hence both overdue and necessary. The last but not least contributing factor is that of the third parties instrumental in the accelerated adjustment that China’s rise necessitated. Help from the Philippines and Vietnam enabled the U.S. to swiftly complete the arrangement by comprehensively utilizing new and old mechanisms through which to intervene in Asia-Pacific issues.

- Xi Elected Chinese President, Chairman of PRC Central Military Commission

- Li Keqiang Endorsed as Chinese Premier

- Fan Changlong, Xu Qiliang Endorsed as Vice Chairmen of Central Military Commission of PRC

- New Leadership Elected for China's Top Legislature

- Proceedings Initiated for China's Leadership Change