Small Railway Station: Witness to a Century of Change

By staff reporter ZHOU LIN

THE Qingdao-Jinan Railway, 500 or more kilometers southwards of Beijing, was built throughout the last century on the vast expanses of Shandong Province – homeland of the sage Confucius. Nowadays, the diminutive 112-year-old train station in Fangzi District, Weifang City, is one of the oldest and best preserved stations on the east-west railway.

Covering an area of less than eight square kilometers, most of the 103 German-style edifices and 69 Japanese buildings that make up Fangzi District are dilapidated and time-ravaged. The daily freight locomotives are the only trains that pass through. The station house, the telegraph building, guard station, and coal loading depot, all largely disused, mutely narrate the 100-year history of the station.

|

|

|

The original location of Fangzi Station. Xu Jianjun |

History of Fangzi Station

Xu Shirong is a local resident, born in Fangzi in 1928. His family lives in an adobe house near the station. A left turn from Xu’s home leads to Fangzi station square, on one side of which stands a hotel, and on the other the telegraph building. Emblazoned on the front of the yellow station house in bold black characters is the legend “Fangzi Station.”

“Originally, this area was nicknamed ‘Jasmine Street’ because of the large clump of Sophora flowers that grew there. Their constant and pervasive fragrance prompted locals to affectionately dub it ‘Jasmine Street,’” 88-year-old Xu Shirong told our reporter. Xu has a sound physique, a clear mind, and is neither deaf nor presbyopic. He speaks of the history of Fangzi Station as if recalling family heirlooms.

Xu Baoshan, Xu Shirong’s father, born in 1874, originally lived in Jiaozhou, southwest of the Shandong Peninsula. In 1906, Xu Baoshan came to Fangzi while working on the locomotive depot built for the railway. The newly-constructed station situated opposite the locomotive depot was named after the nearby village, and so known as Zhangluyuan Station, but in 1915 the name changed to Fangzi Station. Germans constructed the telegraph building, railway car inspection segment, site warehouse, locomotive depot, hydropower segment, and guard house as adjuncts to the train station. This complete network guaranteed the secure operation of the railways.

As Xu Shirong learned from his father, Germans built the railway to transport coal from Fangzi to the port of Qingdao, where German naval ships refueled. Records show that 29.99 million tons of coal was transported from this tiny area during the German occupation of Fangzi.

A museum of coal mining history stands nearby the station. Curator Zou Yuxian explained that renowned geologist Ferdinand von Richthofen wrote a report in 1877 to the German government on Shandong Province’s geological environment and mining resources. He vividly extolled the expansive terrain west of the Shandong Peninsula as a winding black silk belt glistening with glossy black coal and iron deposits.

The entire Qingdao-Jinan Railway formally opened to traffic in 1904. Since then, coal resources in the Fangzi area have been regularly transported to the port of Qingdao for direct shipment overseas.

When Xu Baoshan first arrived at Fangzi, it comprised only two villages – South Zhangluyuan and North Zhangluyuan – surrounded by vast croplands. As the area in front of the railway station was thickly wooded, the road fronting the station square was named Maolin (thick forest) Street. The development of coal mining and the construction of Fangzi Station attracted a large labor force. Bunk houses with thatched corn straw roofs gradually appeared, and travelers and tourists from around the nation crowded the square. Various shops and stores sprang up, as well as the British and American Tobacco factories and the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company. Fangzi thus became the most bustling commercial entrepôt along the Qingdao-Jinan Railway, necessitating the paving of five new roads parallel to Maolin Street.

“Fangzi Station extended in all directions; cargoes came from all over the nation, for instance, from Anqiu to the south, Changyi to the north, Gaomi to the east, and Zhangdian to the west. With its abundance of cargoes and hordes of travelers, the economy here also boomed,” Xu Shirong said.

During WWI, the Japanese, as victors over Germany in their 1914 battles, assumed the administration of Shandong, including Fangzi Station. In January 1923, The Chinese government received Fangzi back from the Japanese. However, after the outbreak of Japanese aggression against China in 1937, the Qingdao-Jinan Railway again fell into the clutches of the Japanese until the end of the war. In Xu Shirong’s youthful memories all station managers were Japanese.

|

|

|

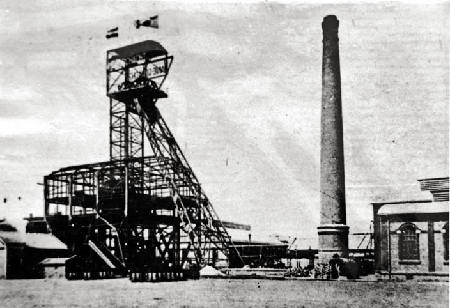

The Fangzi coal mine built by Germany in 1898. |

“Supernatural” Locomotive Drivers

In 1942, then 14-year-old Xu Shirong became a railway worker at the Fangzi locomotive depot. He initially did menial tasks in the maintenance office, like sweeping the floor and helping with odd jobs. He also worked on train maintenance.

Unlike his father, Xu Shirong’s dream was to become a locomotive driver. For the elderly, the most unforgettable memories are of driving real locomotives in the steam era. A popular saying at the station described locomotive drivers as “having the supernatural power to stand on air, one foot above the ground.”

In 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was founded, Xu Shirong’s dream eventually came true.

Talking about different styles of locomotives, Xu Shirong is unable to suppress his excitement, and his eyes sparkle. “All the locomotives running on the Qingdao-Jinan Railway at that time were made by foreign countries such as Germany, the U.K., Hungary, Czechoslovakia and the U.S. But when I came to work at the station, it had already been occupied by the Japanese. Therefore, I gained a deep impression of Japanese locomotives.”

According to elderly locals, from the early 20th century to 1960, almost half a century had elapsed without a single locomotive being made in China. An array of various locomotives originating in different countries rendered the work of inspection and maintenance onerous, as did obsolete designs and a lack of parts. Workers often complained of the low efficiency and labor-intensiveness of their work.

In 1952, Sifang Locomotive Factory (now CSR Qingdao Sifang Co., Ltd) successfully produced the first steam locomotive – Jiefang (meaning liberation, known as the “JF” type), thereby opening a new chapter in the history of China’s steam locomotive production.

In September 1956, Dalian Locomotive Factory (now CNR Dalian Locomotive and Rolling Stock Co., Ltd) devised China’s first high-power locomotive for a freight trunk line – Qianjin (meaning advance, known as the “QJ” type), all the technical indicators of which attained an advanced level among the world’s steam locomotives. After a series of improvements carried out at Datong Locomotive Factory (now CNR Datong Electric Locomotive Co., Ltd) in Shanxi Province in 1964, the QJ locomotives attained 2,190 kw in maximum wheel circumference power, and the overall length of locomotives increased to almost 30 meters. In the 1980s, the Datong locomotive depot had the largest fleet of QJ locomotives in the nation, at one time more than 200 in total.

Xu Shirong, who is highly conversant with foreign locomotives, said that the gradual appearance at Fangzi Station after 1958 of “Liberation”, “Construction” and “Advance” freight locomotives, and “People” passenger locomotives was a matter of great honor.

As did his father before him, every day Xu Shirong walked over to Fangzi Station to do a day’s work and then returned home. The yellow station houses, the rails extending in a straight line, the platform paved with dull red bricks, all fused together at that time and suffused Xu’s blood, becoming a part of his life.

Close Ties between Four Generations and Railways

On July 1, 1977, Xu Shirong’s second son, Xu Zhonglin, took over his father’s work on returning home from the army. He became a railway worker at the Fangzi locomotive depot in charge of stoking coal to fuel the steam engines. Xu Shirong thus had no choice but to leave his beloved Fangzi station, but his love of railways, Fangzi station and steam locomotives has never left him, and he has passed it all on to his descendants.

Experiencing the development history of China’s railway locomotives, from steam to diesel locomotives, and then to electric ones, Xu Shirong preserves a deep impression of every detailed moment. “Since the 1980s, steam locomotives have been gradually phased out; and between 1985 and 1996, all the locomotives were replaced by diesels,” Xu explained. “After several rounds of increases in train speed, all the trains running on the Qingdao-Jinan Railway are now drawn by electric locomotives.” In 2007, a passenger dedicated railway was finally established between Qingdao and Jinan, on which new bullet trains head for Beijing and Shanghai. This has not only injected fresh vigor into the century-old railway line, but also realized the dream of an old locomotive gaffer like Xu Shirong.

In July 1984, Fangzi Station became downgraded to a feeder station as the railway line was rechanneled in a reconstruction project. Passenger trains no longer passed through it, and the volume of freight trains also dramatically decreased. All departments, such as the locomotive depot, track maintenance division, car depot, and electricity and water supplies, have been discontinued, leaving only freight transportation and station security. Xu Zhonglin has transferred to a job as a passenger clerk at Weifang Station. Nowadays, Xu Shirong’s grandson Xu Xiaokun works at the communication and signal division in Weifang Station.

Xu Shirong today receives a monthly pension of more than RMB 7,000. He has chosen to live on in his un-renovated single-story house near the railway station, with its red bricks and tiles and big green steel door with a large poster bearing the Chinese character for “Fortune.” His paintings and family photos of generations of railway workers hang inside the house.

Sitting beneath trees in the courtyard of his home, Xu Shirong often thinks of the good old days at Fangzi Station. One hundred years have quietly passed by since 1906, when his father traveled from his hometown to settle in Jasmine Street. Xu Shirong’s father, Xu Shirong himself, and his son and grandson – altogether four generations – have all witnessed, and still are witnessing a century of changes at Fangzi Station, and likewise of the larger history of China’s railway development.