The Power of the Market

By ZUO SHULA

IN 1992, China set out to establish a socialist market economy system – a move that jump-started reforms to the film distribution system the following year. In 2001, the year negotiations were concluded on China’s terms of membership of the WTO, film was defined as a product of the service and trade sector. Since then, the market force has gradually become predominant in the industry’s development.

A Hard Start

The reform and opening-up policy of late 1978 injected vitality into all China’s industries, especially Chinese cinema. In 1979, the country’s cinema admissions amounted to 29.3 billion, equivalent to 20 film viewings per capita. By 1992, total box office income had reached RMB 3.2 billion. The China Film Group Corporation received government approval in 1994 to import around 10 movies every year on the basis of shared box office receipts. The Fugitive, imported at the end of that year, earned RMB 25 million.

The year 1995 saw reforms to the feature film production management system. By significantly alleviating funding problems the reformed system enabled a large group of provincial film studios to shoot films. Beijing Film Studio obtained around RMB 200 million in investment that year, and produced over 30 films. Among them, In the Heat of the Sun, directed by Jiang Wen, was the top-grossing movie, earning more than RMB four million.

After China entered the WTO on January 1, 2002, institutions other than state-owned film studios were permitted to produce movies. The first independently produced movie, My Father and I, written and directed by Xu Jinglei, went on general release on March 20, 2002. Several of the productions that year by non-state-owned film studios, among them Hero, Big Shot’s Funeral, Warriors of Heaven and Earth, Zhou Yu’s Train, and Cala, My Dog were hugely successful. Hero alone grossed RMB 250 million, and also marked a hike in cinema ticket prices from RMB 20 to RMB 30. Some films were joint ventures with overseas studios, so carrying the advantages of capital, human resources, management and market. But these benefits often constrained – even controlled – these movies, as well as supporting them. American studios like Columbia and IMAR Films inevitably left their imprint on Chinese films.

In November 2002, the cultural industry, including the film sector, was listed as one of the key industries in China’s macroeconomic blueprint. The policy directly stimulated social capital and institutions outside of the industry. Over half of the movies of 2003 were produced either by non-state-owned studios or jointly with foreign companies. The mainland market also fully opened to Hong Kong movies that year.

A New Stage

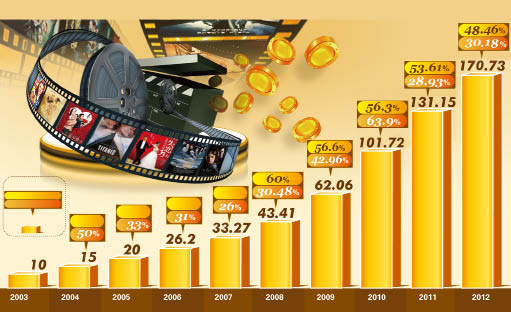

In 2006, 330 feature films were produced in the mainland, and 112 TV films were shot by China Central Television’s Movie Channel. Annual box office returns hit RMB 2.62 million, and maintained a 20 percent or more growth rate for four straight years. The top 10 productions were divided equally between locally made and imported films, the biggest box office hits being the Chinese films Curse of the Golden Flower and The Banquet.

That year, film industry investors surpassed 300, among whom 277 were non-state-owned companies. Of China’s 36 cinema circuits, comprising 1,325 cinemas and 3,034 screens, eight raked in more than RMB 100 million at the box office.

The movie Hero was the first to enter the European and American market through international cooperation. It also marked a new age wherein Chinese movies became cultural goods traded on overseas markets rather than art-house works confined mainly to international film festivals. Hero was also the catalyst for a frenzy of blockbusters and epics in China, such as Chen Kaige’s The Promise in 2005, and Zhang Yimou’s Curse of the Golden Flower and Feng Xiaogang’s The Banquet in 2006.

Big-budget fever had pervaded the Chinese film industry since the huge success of Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, as well as the healthy box office returns that Hero generated in the domestic market. As Chinese film industry needed the overseas market to digest huge investments, the ancient costumes + martial arts mode seemed the safest choice. Both domestic and overseas audiences, however, began to tire of these stereotype productions, and to question the creativity and story-telling capacity of the fifth-generation Chinese directors, as represented by Zhang Yimou, Chen Kaige and Tian Zhuangzhuang.