The Inclusive Spirit of Soong Ching Ling

|

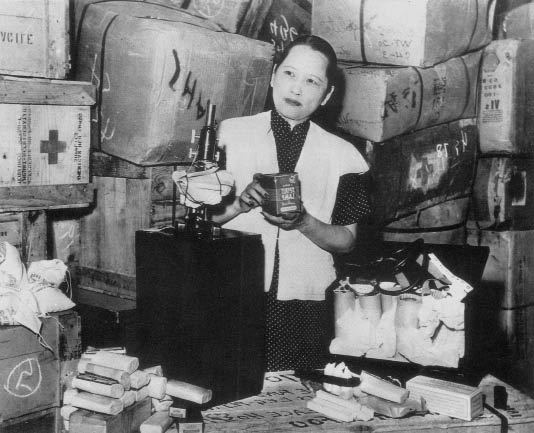

| Soong Ching Ling inspects medical aid to be shipped to the frontline during the war against Japanese invasion. |

By LU PING

IT’S been 32 years now since Soong Ching Ling, honorary president of the People’s Republic of China, left this world. Today, we continue to cherish her memory and value her contributions to mankind.

I had the honor of working alongside Soong, and learned a great deal from her.

In my mind, Soong was like a glittering jadestone that refuses to hide itself in the ground. The shifting sands of time were never able to obscure her radiant spirit. In her life, she was a ray of sunshine that pierced through the dark clouds of domestic turmoil, bringing hope to all.

She subscribed to the same revolutionary ideals as her husband, Sun Yat-sen, and continued to champion them long after his death in 1925.

In her time, she was widely regarded as the mother of the new nation, an epithet recognized even by Chiang Kai-shek. She was born into a wealthy family, and could have lived a carefree life of abundance. Instead, she chose to stand together with the common man. She fought against reactionary elements within the Kuomintang government and devoted herself to the revolution.

After the liberation of China, she gave all her energy to the construction of New China under the leadership of the Communist Party of China (CPC), exerting her utmost to fulfill her duties until her death. She insisted on knowing, and telling, the truth. She was a good friend of the CPC who did not shy away from constructive criticism.

There is an old photo in the former residence of Sun Yat-sen in Cuiheng Village, Zhongshan City, Guangdong Province, which shows Soong keeping vigil over her husband’s coffin. I used to stand admiring the photo. It was difficult for me to believe that the young and seemingly fragile woman in the photo had such a strong, determined soul. It sounds like a cliché, but in the pursuit of the truth and the betterment of citizens’ lives, Soong was immune to the temptations of wealth and rank. For this, the people held her in high esteem.

A Life Dedicated to the Rights of Women and Children

“Give your best to children,” Soong once said. In her efforts to better the lives of the country’s children, she personally founded the China Welfare Institute (CWI), through which she opened China’s first “children’s palace,” or youth center, and the country’s first children’s theater. Soong spared no effort to create the best conditions for the CWI kindergarten and nursery. On being awarded an international peace prize, Soong contributed all the prize money to the establishment of the International Peace Maternity and Children Hospital. She also founded Children’s Epoch, a publication well known for its playful language and vivid illustrations.

My own, personal experience serves to show that Soong’s reputation as early New China’s most concerned philanthropist was fully deserved. My first job after graduation was at the CWI. World War II had just ended. Numerous lives were lost in the brutal war, leaving hundreds of thousands of orphans. To spare these children a parentless upbringing, Soong, using her reputation abroad, asked for support from an American civil organization, the Foster Parents’ Plan, to establish a branch office in China under the CWI. I worked in the office. Every month, we used donations from the Foster Parents’ Plan to provide orphans with living expenses and supplies. We handed out food and clothing and placed them in schools. Nowadays human rights are championed throughout the world, but back then, they were still just a legal concept. Soong set an outstanding early example in defending the rights of Chinese women and children. She is not only a great role model for China, but also one for the whole world.