Capital Changes

By staff reporter PAMELA LORD

|

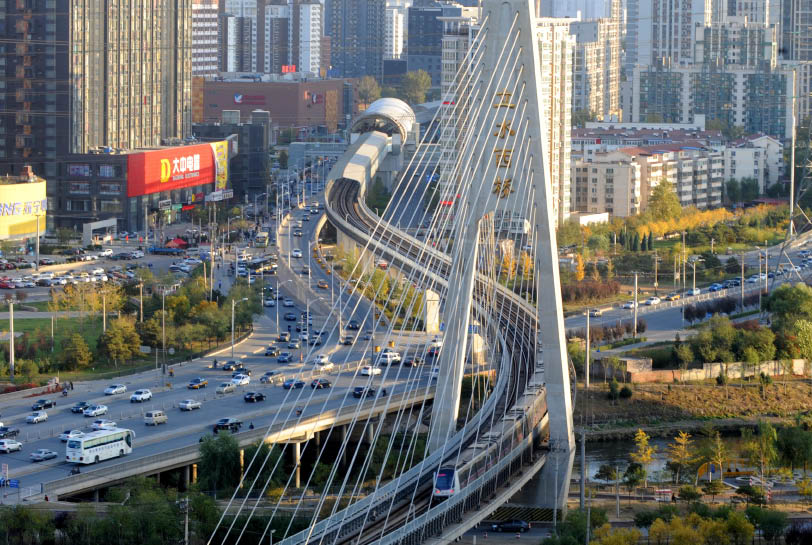

| Subway Line 5 traverses Beijing from north to south. |

THE handover clock in Tian’anmen Square counting down the seconds till Hong Kong’s return to the motherland, smatterings of Cherokee jeeps, yellow miandi mini-buses and red Xiali taxis amid a sea of bicycles, and waistbands sporting bibiji are characteristics of the 1996 Beijing streetscape long since gone.

I came to try my luck at living and working in the capital in 1996, almost two decades after the coming into effect of Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up policy of 1978. The largely positive changes I have since witnessed are testament to China’s generally higher standard of living. The household responsibility system that permitted farmers to sell crops in excess of the government quota on the free market halved poverty during the years 1981 to 1987. It fell a third more during the three years after China’s WTO membership in 2001. Most young people of the so-called post-90s generation have never experienced hunger or want.

In 1996, as now, building cranes stalking the city horizon signified ongoing mass urban construction. Pagers, rather than cell phones, were ubiquitous, the latter distinguishing relatively moneyed go-getters from those dashing to the nearest public phone at the beep of their so-called bibiji.

In Tian’anmen Square, meanwhile, a huge countdown clock ticked off the days, hours, minutes and seconds to July 1, 1997, when Hong Kong was restored to the motherland after 100 years as a British colony.

The unisex uniform of white blouse and navy trousers of the 1980s more or less defunct, the youth generally strode out wearing jeans, T-shirts and brand sports shoes. Hairstyles were relatively conservative in comparison with the androgynously gamine style common among young adults since the so-called Korean wave, or Hallyu, hit China in 2001. But you would see among the crowd the occasional head sprouting punk-style peroxided locks.

Getting About

New roads and an expanded subway have considerably improved everyday life for Beijing residents over the past decade and a half. Locals now have more spare time in which to sing, dance, climb mountains, go to the movies, or play with their iPhones as they please.

The subway map in 1996 resembled a fly swatter, comprising Line One, from west to east and the circular Line Two. Public buses could consequently be likened to sardine cans on wheels. The Beijing subway began its gradual expansion with an extension in 1999 of Line One. Line 13 opened in 2002 and the Batong line in 2003. The year 2007 saw the opening of Line 5 and 2008 – year of the Beijing Olympics – of three new lines: Line 8, Line 10 and the Airport Express Line from Dongzhimen.

These improvements made obsolete certain modes of public transport current in the late 1990s. Having lived in both Changping in the far north and Daxing in the sultry south of Beijing, I was a frequent traveler on privately run mini buses that, for around RMB 5, offered a quicker but decidedly more perilous journey downtown than by standard public bus. Three-wheelers, however, survived, and hutong tours have sparked a tri-shaw revival.