By staff reporter NINA VICKERY

By staff reporter NINA VICKERY

WHEN I was about 13 years old, a shop called Shaolin opened up in my hometown in southeast England. At that time, I had no idea what or where the name Shaolin came from – my friends and I would pronounce it “shay-oh lin” – but after my first visit to the shop, I was certain it would become a firm favorite on our list of places-to-hang-out on a Saturday afternoon.

Shaolin was an Aladdin’s cave of Chinese goods. On entering, you were first struck by atmospheric, dim lighting and the heady smell of incense. Then, the sounds: A CD of bamboo flute music accompanied by sounds of nature, and the tinkle of wind chimes evoked a sense of calm that made you want to stop and browse. For me, these sensory experiences became synonymous with “the Orient,” and that was before I’d seen what the shop sold.

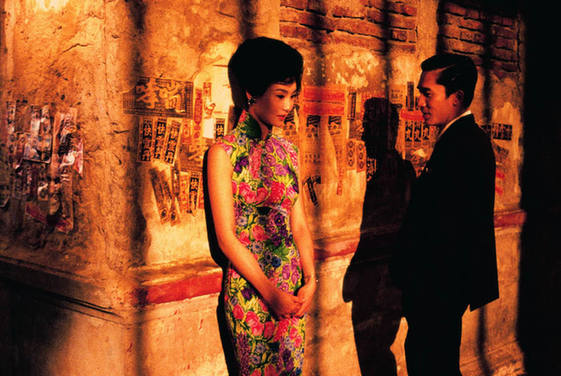

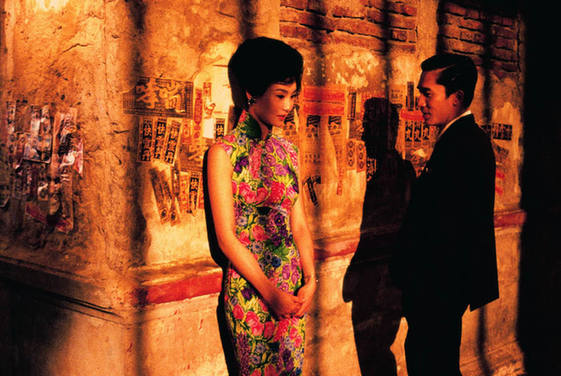

Silk bags and purses lined the walls; joss sticks of every fragrance imaginable took up a whole corner; Chinese meditation balls in their silk-lined boxes were displayed in the central aisle; and smaller pocket-money items like recycled paper notebooks with yin-yang symbols on the cover and “mood rings” that changed color and gave insights on your current frame of mind (and were, therefore, a big hit with teenage girls) were found by the counter. And on a rack by the window was an array of beautiful, silk qipao of varying lengths and colors.

Most weekends, I would go to Shaolin and eye these sleek dresses wondering whether they would look any good on me, but never daring to try one. The elegant qipao with its distinctive mandarin collar and slit skirt became something of a fixation that contributed to the picture of China in my mind. Little did I know that 17 years later I would be living in China and have the opportunity to explore Chinese fashions of the past and present up close.

When I first arrived in Beijing at the height of summer, the fashions sported by young men and women caught my eye. The men wore T-shirts in bold colors and designs and were not afraid to express their individuality through wild hairstyles, while the women embodied femininity with floaty dresses and chic heels; but to my disappointment there was not a qipao in sight. In fact, the history of the dress tells us that it did not start out with the 1920s Shanghai style and grace one thinks of today, and current opinions on an apparent revival of the qipao as everyday wear are divided.

The qipao, also known as the cheongsam, originated in Manchurian China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) when certain social strata emerged, among them the Banner People. Qipao translates as “banner gown” and was originally a long, wide, loose-fitting garment. Legend has it that a fisherwoman, feeling hindered by the expanse of material in her dress, set to work to make it more practical and tailored a long gown with slits up each side that would enable her to tuck her dress in at the front. At the same time, the young emperor had a dream that foretold that a fisherwoman wearing a qipao would one day become his consort. On waking, the emperor sent his men out to look for the woman and sure enough, they came across the fisherwoman. She became the emperor’s wife and soon, Manchu women began to copy her new style of qipao.